Request to Northampton Police on Face Surveillance Technology

Request Submitted To: Northampton Police Department

Category: Surveillance

Year Filed: 2019

Background

In June 2019, the ACLU of Massachusetts launched a campaign to “Press Pause” on the government’s use of face recognition and other at a distance biometric surveillance technologies. As a part of that campaign, we have filed dozens of public records requests with police agencies across the state, to learn about how they are using these technologies, and to learn about how companies are marketing their products. We filed a request with the Northampton Police Department and received hundreds of pages of documents in return, mostly marketing materials from surveillance companies eager to sell their products.

Minutes from Boston Area Homeland Security Meetings

Request Submitted To: City of Boston Office of Emergency Management

Category: Law Enforcement

Year Filed: 2018

Background

The City of Boston is the host city for the Boston Metro Homeland Security Region (MHSR), so designated to receive federal dollars from the Department of Homeland Security through the Urban Areas Security Initiative (UASI) funding stream. The MHSR routinely meets to discuss emergency preparedness, surveillance, and information sharing. Boston, Chelsea, Winthrop, Revere, Cambridge, Quincy, Brookline, Everett, Revere and Somerville are included in the Boston UASI region.

- 16.02.02 Meeting Minutes APPROVED 4.4.16

- 16.02.16 Intel Minutes

- 16.03.02 Intel Minutes

- 16.04.04 Meeting Minutes – APPROVED

- 16.05.09 Intel Minutes

- 16.06.09 JPOC Meeting Minutes APPROVED 9.13.16

- 16.09.13 JPOC Meeting Minutes APPROVED 12.7.16

- 16.11.28 Intel Minutes

- 17.01.04 JPOC minutes APPROVED

- 17.01.04 JPOC Minutes FINAL

- 17.01.17 Intel Meeting Minutes

- 17.02.01 JPOC Minutes – APPROVED

- 17.03.07 Intel Mtg Minutes

- 17.04.05 JPOC minutes APPROVED 6.14.17

- 17.06.14 JPOC minutes APPROVED 9.6.17

- 17.09.06 JPOC minutes APPROVED 10.4.17

- 17.09.14 Intel meeting minutes DRAFT

- 17.10.04 JPOC minutes APPROVED 12.6.17

- 17.10.12 Intel meeting minutes

- 17.11.16 Intel meeting minutes DRAFT

- 17.12.06 JPOC Minutes APPROVED 1.3.18

- 18.01.03 JPOC Minutes APPROVED-18.02.07

- 18.01.18 Intel meeting minutes DRAFT

Plymouth Police Department Face Surveillance Emails

Request Submitted To: Plymouth Police Department

Category: Surveillance

Year Filed: 2018

Background

In July 2018, the ACLU of Massachusetts filed requests with dozens of police departments to learn about how they use face surveillance technology. The Plymouth Police Department provided hundreds of emails in response to that request. The emails contain a years long correspondence between a billionaire-backed face surveillance start-up called “Suspect Technologies” and representatives for the Plymouth Police Department.

Related media:

‘They Would Go Absolutely Nuts’: How a Mark Cuban-Backed Facial Recognition Firm Tried to Work with Cops, Joseph Cox, May 6, 2019, VICE.

Local face recognition company wanted police to share your private information, May 6, 2019, Fox 25 News.

Data collection practices of voice and facial biometrics companies criticized, Chris Burt, May 7, 2019, Biometric Update.

Firm Targeted MA Police Departments For Facial Recognition Tech, Dave Copeland, May 6, 2019, Patch.

Somerville moves to ban facial recognition surveillance, Andy Rosen, May 10, 2019, Boston Globe.

Massachusetts Use of Facial Recognition Technology

Request Submitted To: Massachusetts State Police

Category: Surveillance

Year Filed: 2017

Background

The purpose of this request was to learn more about the use of face recognition technology at the Massachusetts State Police and its fusion center, the Commonwealth Fusion Center.

Boston Police Filming Protesters at BPDA Meeting

Request Submitted To: Boston Police Department

Category: Law Enforcement

Year Filed: 2017

Background

On March 2, 2017, members of the Boston Police Department were photographed filming protesters at a contentious Boston Planning & Development Agency meeting. This request sought documents and information about a directive to film protestors at this meeting.

New Bedford Field Interrogation and Observation Reports

Request Submitted To: New Bedford Police Department

Category: Law Enforcement

Year Filed: 2015

Background

In 2015, we filed a public records request with the New Bedford Police Department (NBPD) to seek “Field Interview & Observation” (FIO) reports completed by the NBPD between 2012 & 2014.

A high-level analysis shows:

- While Black people were estimated to comprise 7.4 percent of the 2013 5-year population of New Bedford, they made up 56.6 percent of stop subjects. This is a 49.2 percent disparity between the observed stop rate and expected stop rate based on race data.

- While white people were estimated to comprise 75.8 percent of the 2012 population of New Bedford, they made up 40.5 percent of stop subjects. This is a 35.3 percent disparity between the observed stop rate and expected stop rate based off of race data.

- While Hispanic people were estimated to comprise 17.5 percent of the 2013 population of New Bedford, they made up 26.1 percent of stop subjects. This is a 8.6 percent disparity between the observed stop rate and expected stop rate based on race data.

- While Non-Hispanic individuals were estimated to comprise 82.5 percent of the 2012 population of New Bedford, they made up 71.7 percent of stop subjects. This is a 10.8 percent disparity between the observed stop rate and expected stop rate based off of race data.

Policies

- NBPD Policies 512-514 use of force & weapons

- NBPD General Order re Use of Less Lethal Force

- NBPD General Order re Use of Deadly Force

- NBPD General Order re FIO Report

- NBPD Gen Order #14-06 custodial procs

- NBPD Gen Order #3-20 antidiscrim harassment

- NBPD DDirective re High Energy Patrol Initiative

- NBPD Directive – Operation S.T.A.N.D.

- NBPD Directive – High Energy Patrol Initiative

- Certification Handbook

- ACLU follow up about 7/1/15 request

- NBPD Response with documents

Field Interrogation & Observation Reports

Social Media Monitoring by Boston Police

Request Submitted To: Boston Police Department

Category: Surveillance

Year Filed: 2016

Background

In October 2016, the Boston Herald reported that Boston Police Department (BPD) had published a $1.4 million request for proposals (RFP) to purchase a social media surveillance system. In response, companies submitted proposals detailing social media monitoring systems that claimed to enable advanced surveillance and tracking. Boston Police Commissioner William Evans told local media the police wouldn’t use such a tool to track anyone but serious criminals. “We’re not going after ordinary people,” Evans told WGBH in November 2016. “It’s a necessary tool of law enforcement and helps in keeping our neighborhoods safe from violence, as well as terrorism, human trafficking, and young kids who might be the victim of a pedophile.” But when faced with public backlash after the ACLU of Massachusetts and Bostonians raised public concerns about BPD’s plans, the police commissioner scrapped the RFP and, at least for now, has publicly stepped away from plans for a new social media monitoring system.

In fact, this was not BPD’s first foray into automated social media surveillance. Documents obtained by the ACLU of Massachusetts show that BPD’s Boston Regional Intelligence Center (BRIC) used a social media monitoring tool called Geofeedia during the years 2014, 2015, and 2016.

But Geofeedia was soon to come under intense public scrutiny. In September 2016, the ACLU of Northern California published records showing that Geofeedia marketed itself to law enforcement as a tool to keep track of dissidents. In October 2016, the ACLU obtained records showing Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook were making user data available to the company. Ultimately, as a result of the ACLU’s advocacy, all three of the social media giants kicked Geofeedia off their platforms altogether. Since Twitter posts made up a majority of the content Geofeedia scanned and made available to its customers in law enforcement and marketing, this move effectively killed the social media monitoring company.

While Geofeedia may be history, BPD’s use of the tool in 2014, 2015, and 2016 tells an important story about BPD’s approach to social media monitoring. To uncover that story, the ACLU of Massachusetts filed a public records request with BPD, requesting information about how BPD used Geofeedia.

Read our report, Social Media Monitoring in Boston: Free Speech in the Crosshairs:

View documents on Privacy SOS:

The email alerts that were received as part of this public records request were extracted into a dataset for aggregate and detailed analysis.

Drone Use by Boston Police Department

Request Submitted To: Boston Police Department

Category: Surveillance

Year Filed: 2017

Background

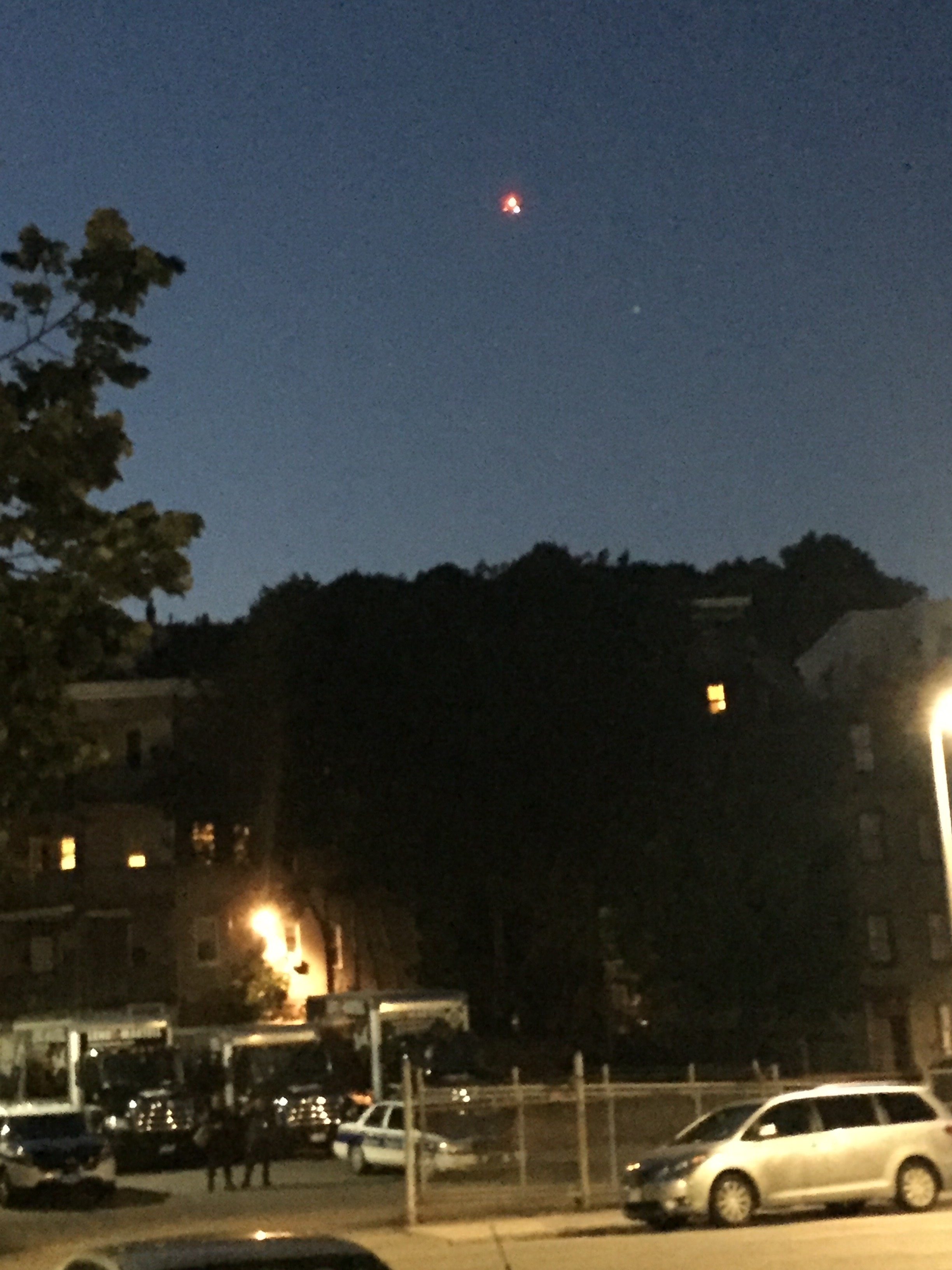

On Saturday, July 15, 2017, neighbors approached Jamaica Plain resident and community activist Corey McMillen with some startling news: there was a drone flying around their housing project. Corey went outside to look, and sure enough, he saw two Boston Police squad cars, two officers, and a buzzing drone with a red light on it. “One officer had the drone in his hand,” McMillen told the Boston Globe. “He let it go and flew it 20 to 25 feet in the air. He seemed to be testing it out.”

After Corey confirmed with his own eyes what his neighbors had seen, he called the ACLU. “Some Boston Police officers are flying a drone in my community,” he said. We were startled. After all, the Boston Police Department had never announced that it planned to purchase any drones. We pay close attention to law enforcement surveillance in Boston and surrounding areas, and this was the first we had heard about the BPD using drones. We asked Corey to take some photos, which he promptly did, and told him we’d look into it.

In response to this troubling tip, we filed a public records request to seek out more information about any unsanctioned drone use by Boston Police Department. Specifically, we sought budgetary records, technical specifications, internal policies, and memoranda, as well as records that could tell us more about what exactly the BPD officers were doing flying a drone in Jamaica Plain on July 15. Specifically, we wanted a legal justification from BPD for deploying the drone that day, as well as the video, images, or audio the drone collected on its flight.

Administrative Subpoena Use by District Attorneys

Request Submitted To: Various Commonwealth District Attorney's

Category: Surveillance

Year Filed: 2017

Background

When the government wants to listen in on your phone calls, it needs to take an oath to a judge affirming that it believes you are involved in criminal activity. If the evidence looks good, the judge will provide it with a warrant. When everyone used landlines to communicate, this system worked.

But now that most people travel with and use their mobile phones everywhere they go, law enforcement’s interest in our telephones has changed substantially. Many times the actual spoken words — the content — of telephone conversations are less useful to investigators than the transactional details of the calls you make. Transactional records, also called ‘metadata,’ show the GPS location from where calls were made, the numbers called, and the dates and times the phone was used. Email metadata reveals the information in the ‘To,’ ‘From,’ and ‘CC’ fields, as well as the time and date when the email was sent, and the IP address assigned to the computer that sent it. This information, held by third parties like phone and internet companies, can often tell law enforcement a lot more than they’d be able to discern by listening to what you say over the phone. Unlike us, metadata doesn’t lie. And unfortunately for our privacy rights, metadata is also a lot easier for police to access.

In 2008, the provisions of G.L. c. 271, § 17B were amended to expand the power of Massachusetts prosecutors to obtain information about private communications and associations. As amended, the law allows the attorney general or a district attorney to issue an administrative subpoena to service providers for records concerning private communications if the prosecutor has “reasonable grounds to believe that [such records] are relevant and material to an ongoing criminal investigation.” The recipient of such a subpoena is required to deliver the records to the attorney general or the district attorney within 14 days. Although the statute expressly prohibits the disclosure of the content of electronic communications, information prosecutors may obtain under the statute can reveal substantial, sensitive information about the activities, communications, and associations of Massachusetts persons.

The purpose of this records request was to seek documents and information to understand how this authority was used in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

- ACLU request to MA Attorney General

- ACLU Request to Essex County District Attorney

- ACLU Request to Berkshire County District Attorney

- ACLU Request to Suffolk County District Attorney

- ACLU Request to Plymouth County District Attorney

- ACLU Request to Worcester County District Attorney

- ACLU Request to Hampden County District Attorney

- ACLU Request to Norfolk County District Attorney

- ACLU Request to Cape & Islands District District Attorney

- ACLU Request to Bristol County District Attorney

- ACLU Request to Middlesex County District Attorney

- ACLU Request to Northwestern District Attorney

Documents from Middlesex County

- Administrative Subpoena Cyber Request Form 2016

- Administrative Subpoena Paralegal Protocol

- Administrative Subpoena Phone Request 2016

- Administrative Subpoena Protocol

- admin subpoena

- Internet Carrier 2014-2016

- Invest (Internet Carrier) 2014-2016

- Invest (Mobile Carrier) 2014-2016

- Mobile Carrier 2014-2016

Info About Metropolitan Law Enforcement Council

Request Submitted To: Metropolitan Law Enforcement Council

Category: Law Enforcement

Year Filed: 2015

Background

The purpose of this request was to seek information regarding the Metropolitan Law Enforcement Council’s mission, structure, budget, policies (especially those related to unbiased policing, community policing, or use of force), interagency mutual aid agreements, vehicles and equipment, grants, SWAT training materials and policies, and SWAT incident reports.