Flock Gives Law Enforcement All Over the Country Access to Your Location

Police in Texas, Florida, and thousands of departments nationwide can track Massachusetts drivers in real-time — without a warrant, probable cause, or even reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing. Documents obtained by the ACLU of Massachusetts reveal that police across the state are collecting detailed information about the locations of Massachusetts drivers and sharing that information with a network of over 7,000 agencies and organizations all over the country — including in states that have passed laws banning abortion and gender-affirming healthcare for minors, and laws requiring police to conduct civil immigration enforcement operations.

The records and other publicly available information confirm that over 80 Massachusetts police departments have entered into contracts to deploy Flock Safety’s automatic license plate reader (LPR) technology to surveil drivers when they pass one of Flock’s cameras on the roads. Over the past three years, Massachusetts police have spent over $2 million in taxpayer funds on this technology. Many of these departments have been sharing LPR data collected in their jurisdiction with Flock to be entered into its national database, where it can be accessed by thousands of out-of-state police departments and even federal agencies.

At minimum, this dragnet surveillance means warrantless tracking of everyone on the road. At worst, it means a digital police state wherein law enforcement officials in far-flung jurisdictions outside of Massachusetts can track protesters, political opponents, immigrants, patients, and others not suspected of any crime and use the information to hurt them.

What Is Flock and How Does It Work?

Flock Safety is a major player in the LPR industry, contracting with thousands of law enforcement agencies, running LPR surveillance across nearly 7,000 networks, and deploying nearly 90,000 cameras nationwide as of July 2025. The company's CEO claims their technology can eradicate all crime in America — though that's more marketing hype than reality.

License plate readers are cameras that automatically capture and record license plates, locations, and timestamps as vehicles pass by. These AI-enabled systems allow police to instantly track where motorists are now and where they've been.

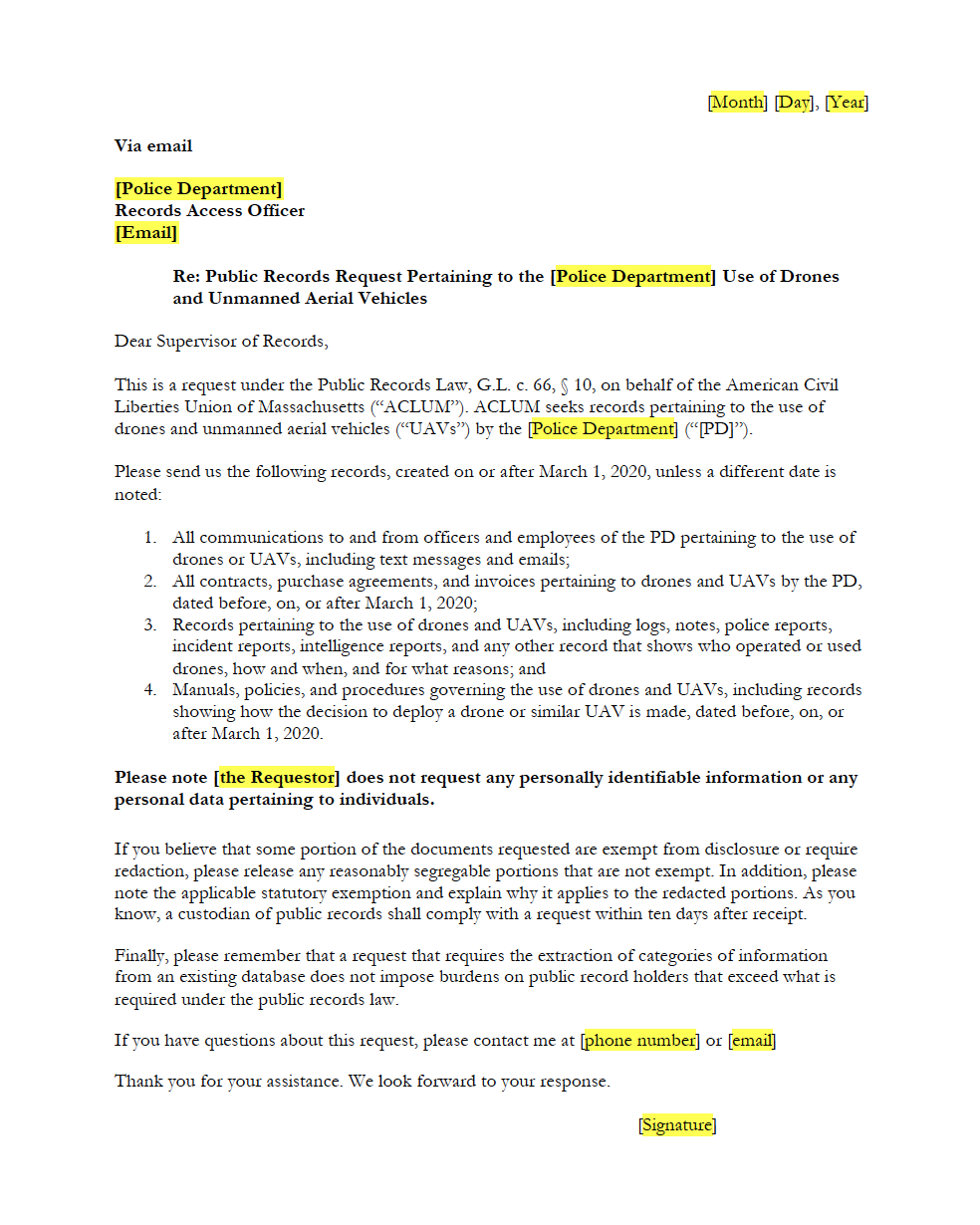

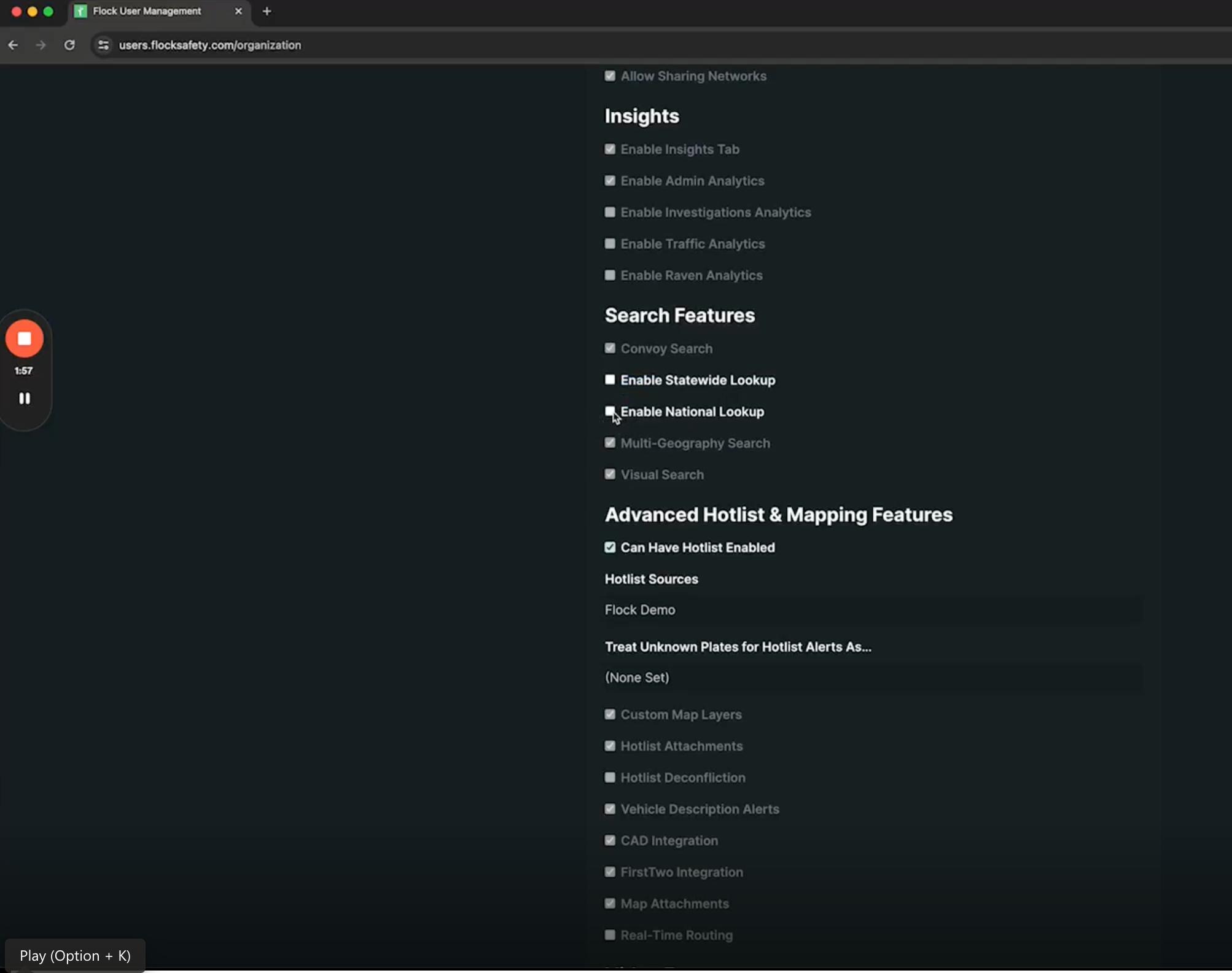

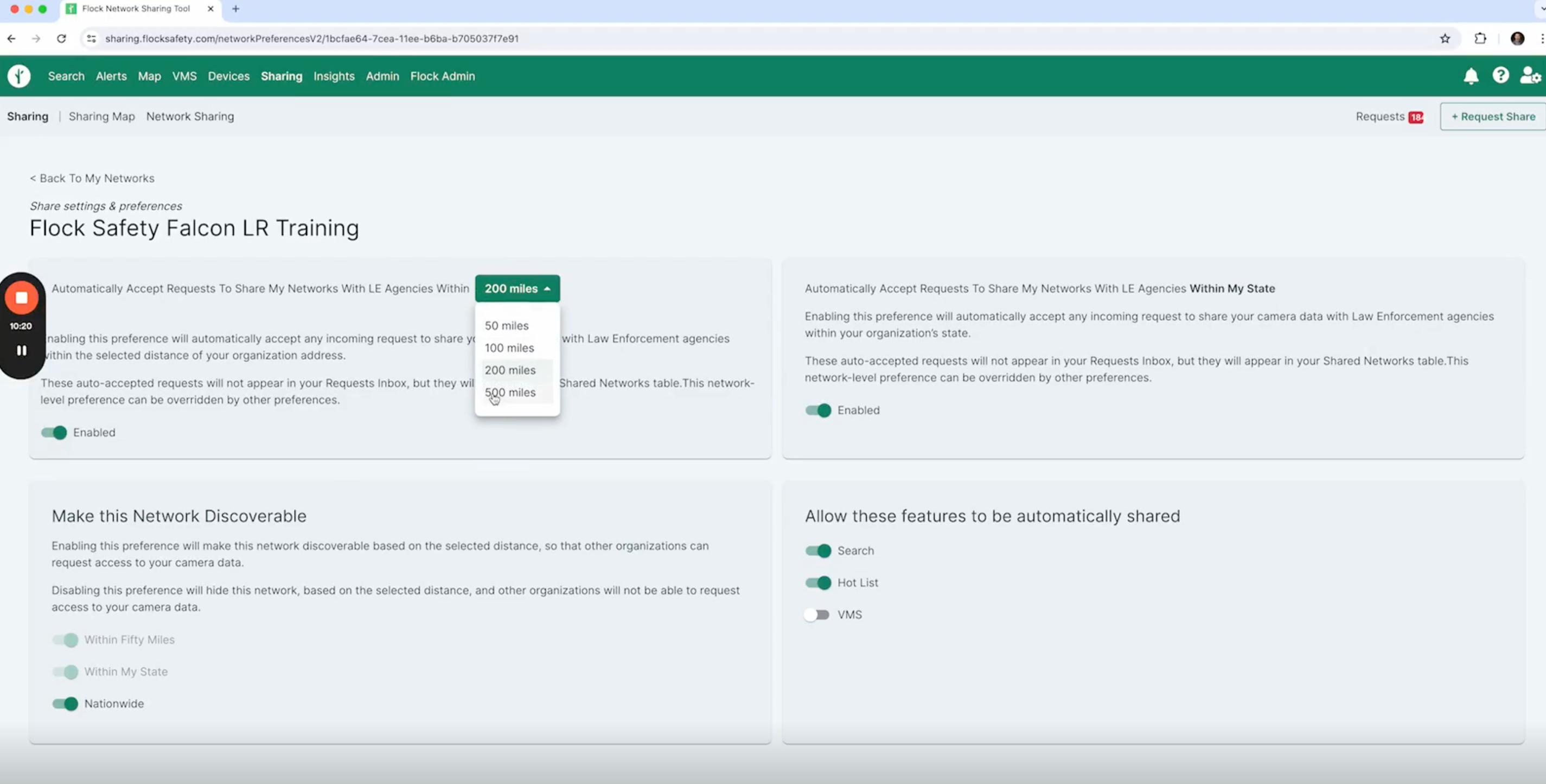

At the crux of the problems with Flock is their nationwide data sharing model. Police departments that contract with Flock can choose to share the LPR data they collect with no other departments, with specific named departments, with all departments in their state, or with the entire Flock network nationwide. But Flock has designed its system to incentivize maximum sharing: if a police department chooses to share their data with the entire nationwide network, that department can also search the entire nationwide network. In effect: “You show me yours, I'll show you mine.” This Flock training video received in response to public records requests demonstrates how seamless and unrestricted data sharing operates within Flock’s system. To share their data with police nationwide, all an administrator needs to do is click a button:

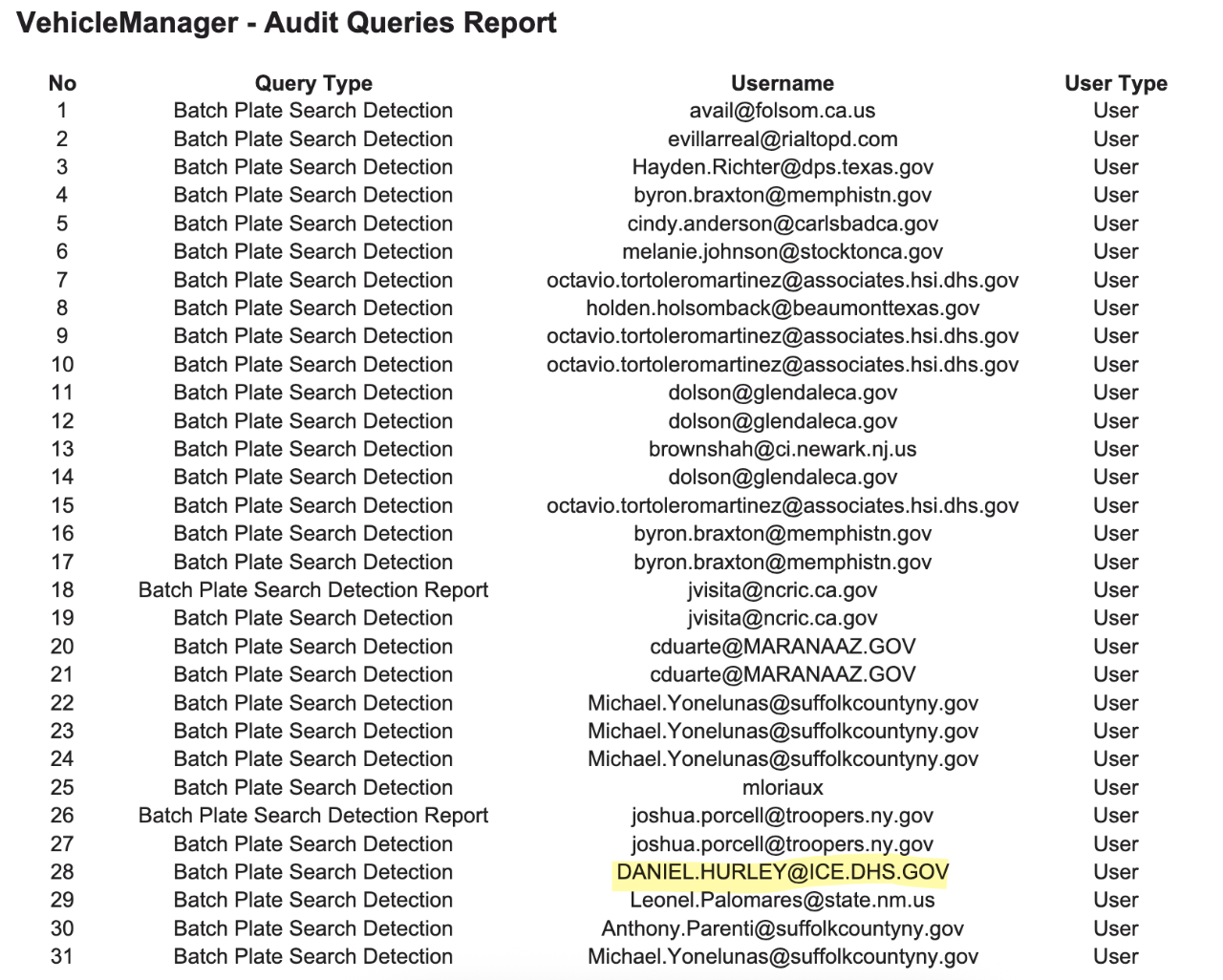

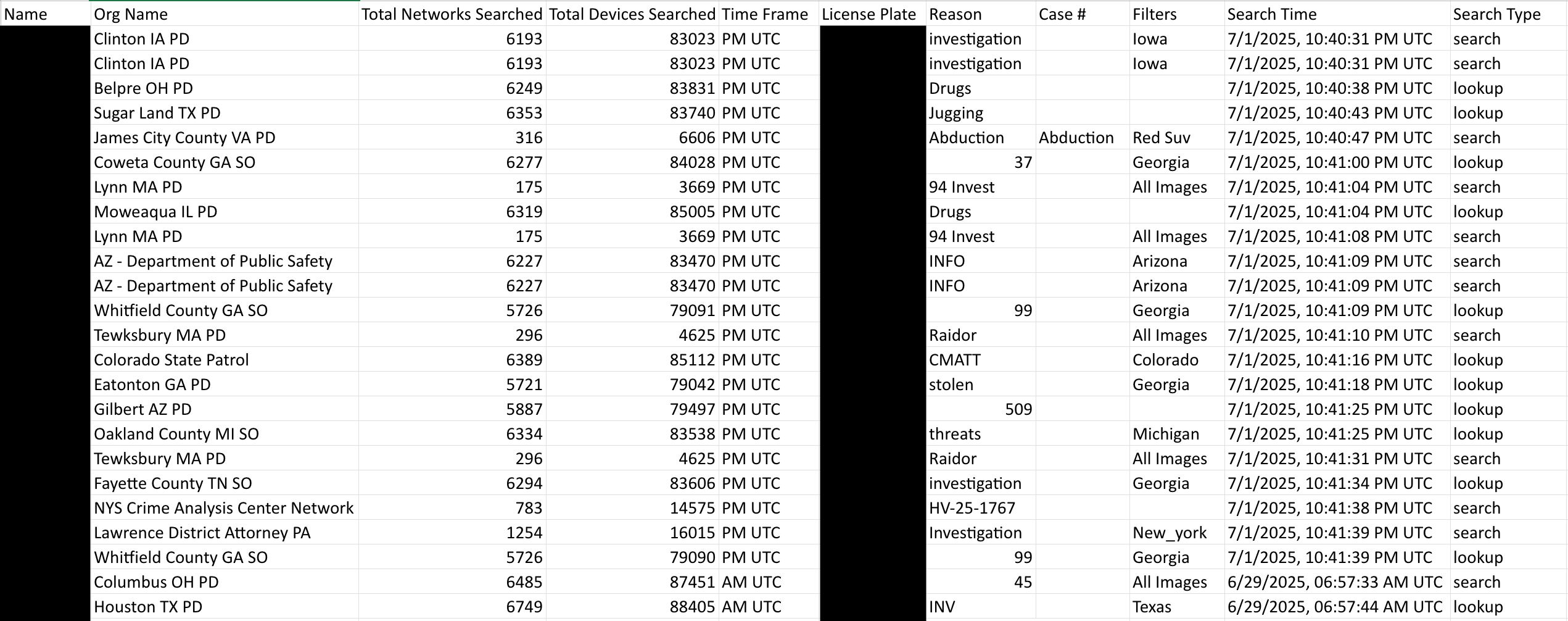

We know many Massachusetts police departments are taking part in this nationwide network because, after submitting public records requests with nearly 80 departments, we received numerous records called “Flock Network Audits[.]” These network audits document searches conducted by police across the country of approximately 7,000 agencies and organizations’ LPR data, including data on Massachusetts drivers collected by dozens of Massachusetts police departments. What this means in practice is that officers with the Florida Highway Patrol and those in Dallas, TX, Jacksonville, FL, Columbus, OH, and thousands of other locations can track where and when Massachusetts residents are driving, even when they are in Massachusetts — all without demonstrating any probable cause or even reasonable suspicion that those people have committed a crime.

Even some federal law enforcement agencies may have access to Flock’s database, despite Flock’s recent assertion that it ended its pilot program with the Department of Homeland Security’s Customs and Border Protection (CBP). News reports indicate local police have conducted searches on behalf of ICE agents.

And that’s not all. Flock isn’t the only license plate reader company with a large presence in Massachusetts. The Massachusetts State Police (MSP) and some local departments also have contracts with Vigilant Solutions, a company that maintains its own national database and has contracts with agencies nationwide — including those in states that have passed extreme restrictions on abortion and gender affirming healthcare access. Vigilant also has contracts with federal agencies, including ICE. Indeed, records obtained through a public records request to the town of Auburn, Massachusetts show ICE agents have direct access to query the Vigilant database. The ACLU of Massachusetts is currently involved in public records litigation to learn more about the MSP’s license plate reader surveillance network and its statewide LPR tracking database. Stay tuned for more details as that litigation progresses.

Is Warrantless, Dragnet Surveillance of Motorists Legal?

In 2014, in Commonwealth v. Augustine, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that police are required to obtain a search warrant to access cell site location information under the Massachusetts Constitution, the Declaration of Rights. Four years later, the Supreme Court applied similar protections nationwide in Carpenter v. United States. The Court reasoned that technology enabling the government to track everyone, to monitor all our public movements, and to do so both in real time and retroactively, posed a significant threat to our Fourth Amendment rights.

LPRs are analogous to cellphone tracking. These AI-enabled cameras track motorists in real-time and historically, giving the government the means to track people's locations in a manner similar to the cell site location information at issue in Augustine and Carpenter.

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court recognized this in 2020, holding in Commonwealth v. McCarthy that “[w]ith enough cameras in enough locations, the historic location data from an [LPR] system in Massachusetts would invade a reasonable expectation of privacy and would constitute a search for constitutional purposes.” Yet today, police in Massachusetts are subject to no state or federal statute governing their use of automatic license plate readers. In the absence of a state statute, police are engaged in mass surveillance of all drivers.

Flock's Data Sharing Model vs. the Massachusetts Shield Law

In August 2024, Massachusetts strengthened its Shield Law, which prohibits Massachusetts law enforcement from providing information or assistance to any other state's law enforcement agency in relation to investigations into reproductive healthcare or gender-affirming healthcare that is lawful in the Commonwealth. The Shield Law was designed to protect people from other states’ laws that criminalize abortion and restrict access to gender-affirming care, ensuring that people who receive and provide protected healthcare that is lawful in Massachusetts can do so without fear of retribution from out-of-state actors.

But Massachusetts law enforcement's use of Flock's nationwide data sharing undermines the effectiveness of the Shield Law. Out-of-state officers from thousands of agencies across the country can and do access information about where and when people are driving in Massachusetts, and there is nothing stopping them from using that information to track the movements of people in Massachusetts who are seeking or providing protected healthcare.

These concerns are not hypothetical. Earlier this year, police in Johnson County, Texas performed a nationwide search in Flock's database to find a woman who they believed had a self-administered abortion — searching LPR data from many states where abortion is legal and protected, including Massachusetts. We know about this investigation because the Texas officer entered “had an abortion, search for female” in the “Reason” field in Flock’s database. Initially, Flock tried to dismiss criticism stemming from the negative press, suggesting that the woman's “family feared she was hurt” and that police merely sought to make sure that she was alright. But subsequent reporting from 404 Media based on public records obtained by the Electronic Frontier Foundation show the police who made this search were pursuing the woman as part of a “death investigation” into the abortion. As 404 Media reporters put it: “In documents created prior to the publication of our article, there is zero mention of concern about the woman’s safety. The records show that the police retroactively created a separate document about the Flock search a week after our article was published, in which they justify the search by saying they were concerned for her safety.”

Flock claims it protects people's privacy and legal rights by requiring all law enforcement officers to enter a “search reason” before accessing database results. According to Flock’s recent response to similar data sharing concerns in other states, if an out-of-state officer enters a reason that would violate a state law that protects access to reproductive and gender-affirming healthcare (for example, Massachusetts’ Shield Law), that state’s LPR data would be excluded from the search results. But the Flock network audits obtained by the ACLU of Massachusetts demonstrate that the company’s measures are woefully inadequate.

The network audits show police frequently enter vague, tautological terms like “investigation” or “susp” instead of information about the substance of the investigation. But even if Flock were to prohibit officers from accessing search data unless they provide a substantive reason, police could evade the system’s guardrails. As Flock's technology attracts more negative media attention and scrutiny from public officials concerned about its data sharing practices, officers in states that criminalize abortion and gender-affirming healthcare could simply decline to provide specific details about their investigations or use terms like “homicide” or “suspicious death” when investigating an abortion case. The scale of the nationwide searches makes case-by-case oversight impossible. For example, a Flock network audit provided to the ACLU of Massachusetts in response to a July 2025 public records request documents over 450,000 searches of the nationwide database in just a 30-day period in the spring of 2025.

Flock’s purported solution to comply with state laws that restrict the sharing of information related to investigations of protected healthcare services is no solution at all. Today, out-of-state officers continue to have effectively unrestricted access to Flock’s nationwide database, including data about Massachusetts residents and visitors.

Flock's Contract Problem

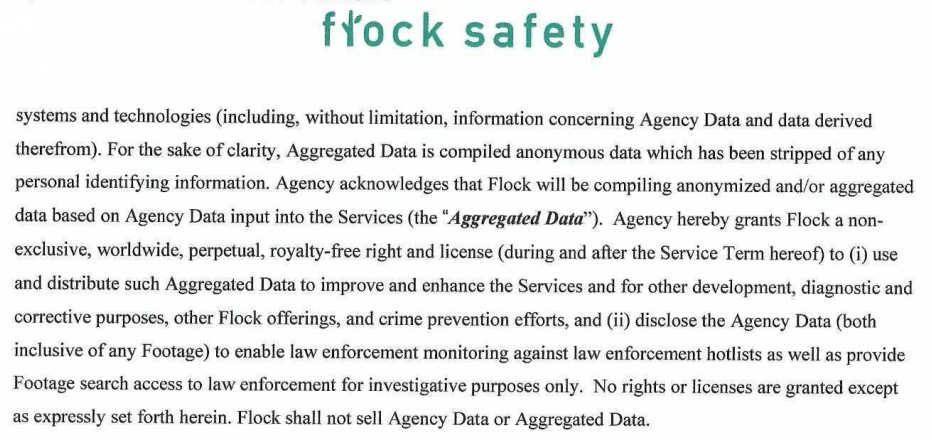

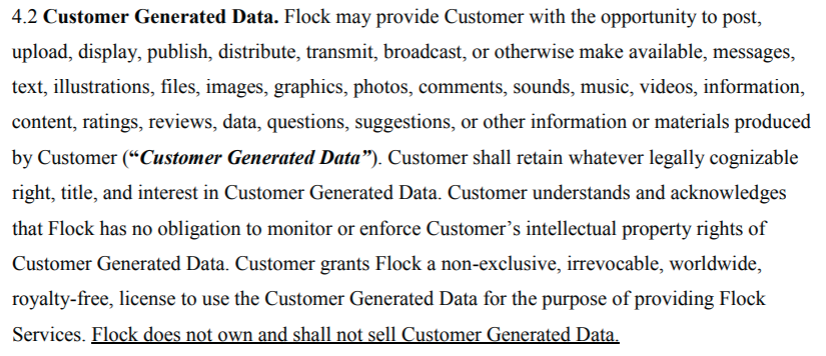

Police departments that use Flock and seek to protect the rights of Massachusetts residents from out-of-state or federal scrutiny must turn off information sharing settings authorizing those entities from searching the data they collect. But even when departments opt to restrict sharing in Flock’s system settings, they may not actually be protecting people’s privacy. According to public records reviewed by the ACLU of Massachusetts, the template user agreement many law enforcement agencies sign gives Flock “a non-exclusive, worldwide, perpetual, royalty-free right and license (during and after the Service Term hereof) to (i) use and distribute [] Aggregated Data to improve and enhance the Services and for other development, diagnostic and corrective purposes, other Flock offerings, and crime prevention efforts, and (ii) disclose the Agency Data (both inclusive of any Footage) to enable law enforcement monitoring against law enforcement hotlists as well as provide Footage search access to law enforcement for investigative purposes only” [italics added for emphasis].

What this means in practice is troubling: even when a police department chooses in Flock's application to restrict data access to its own officers, the template agreement gives Flock the right to disclose the local police department's data both to law enforcement nationwide and federal agencies for “investigative purposes.”

Individual police departments can, and sometimes have, addressed this problem by amending Flock’s contract language. For example, when the Boston Police Department (BPD) conducted a pilot of Flock’s technology earlier this year, the department elected in its sharing settings not to share data outside the department — but the BPD also appears to have rewritten Flock's template contract. Unlike the template contract language that many police departments have agreed to, the Boston Police Department's agreement does not give Flock the right to disclose its LPR data.

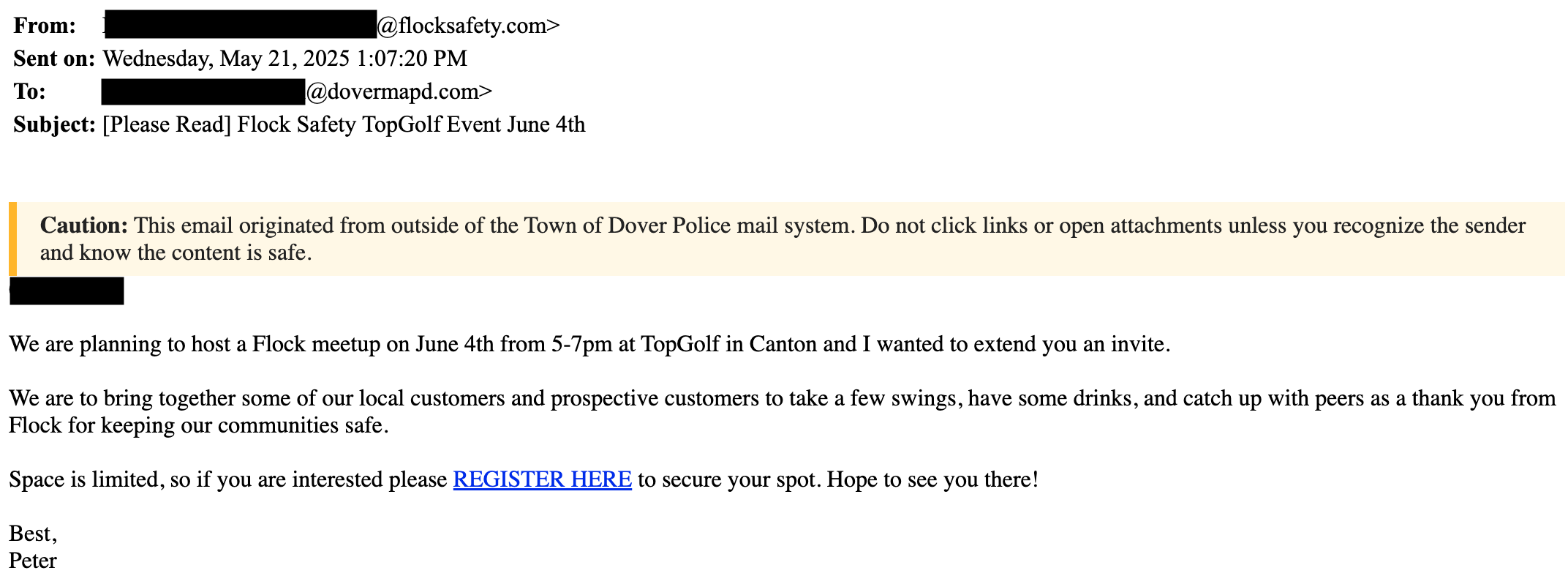

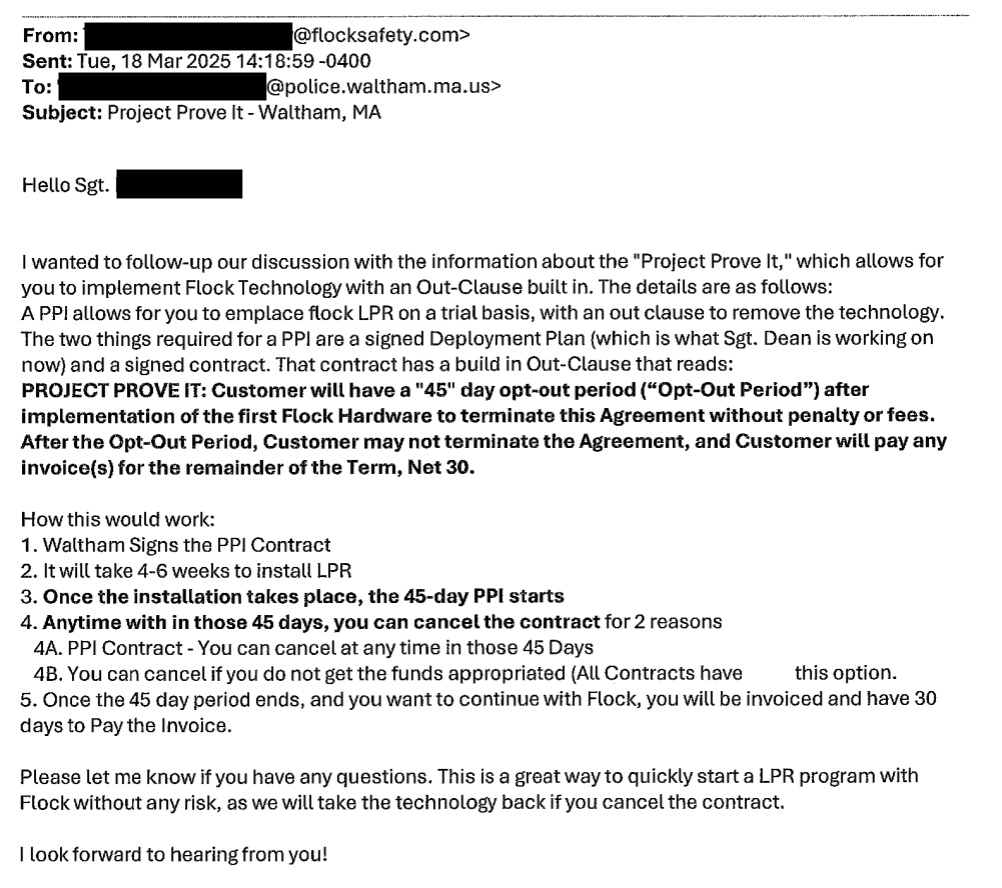

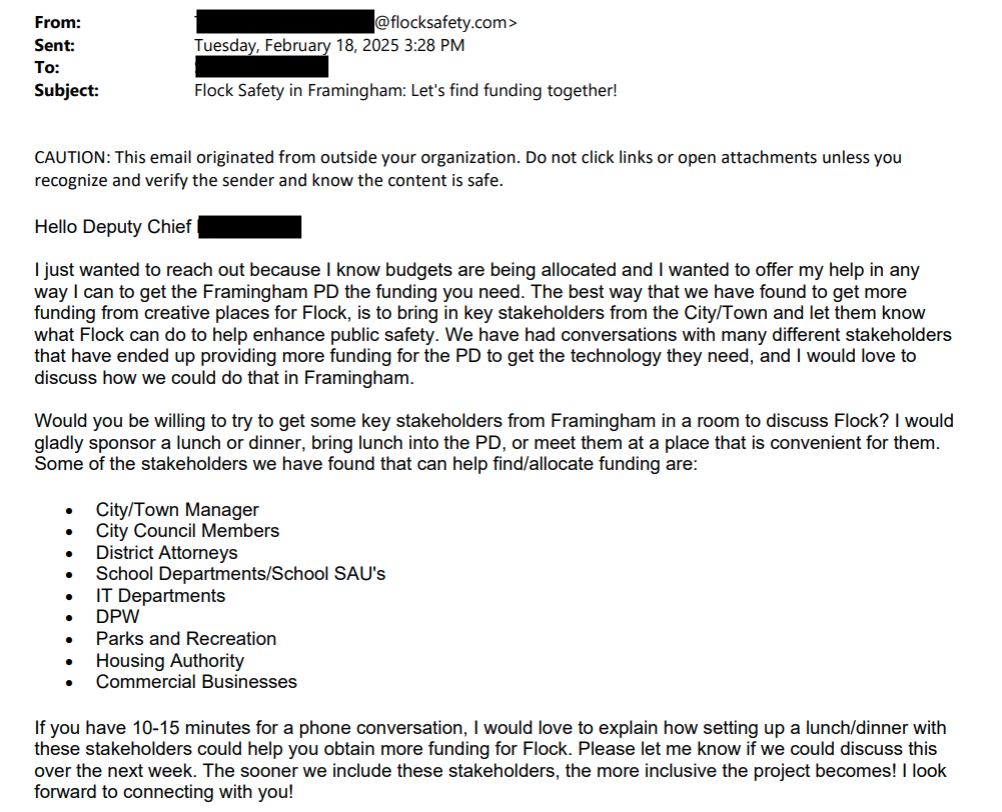

But the vast majority of police departments in Massachusetts lack the legal resources and sophistication of Boston's department, putting them at a serious disadvantage. Flock, which recently received a large investment from Andreessen Horowitz, has been engaged in an aggressive marketing campaign to win more contracts and secure more taxpayer dollars. This campaign includes potent sales tactics, such as invitations to participate in a free TopGolf event and an opportunity for agencies to participate in Flock's “Project Prove It[,]” in which Flock installs LPR cameras on the roads and the agency can back out at no cost within 45 days. Flock sales staff also offer to work with local Massachusetts departments and other municipal leaders to identify and apply for grant funding for Flock LPR systems.

Faced with this onslaught from a company with seemingly endless resources at its disposal, small- and medium-sized police departments across the country are falling prey to aggressive marketing and sales pitches. Individual action by sophisticated departments like Boston’s isn't enough. Residents in communities with less well-resourced departments deserve protection too.

How Lawmakers and Law Enforcement Can Address Issues with LPRs

The scope and severity of this dragnet surveillance make clear that both legislative action and individual police department changes are needed to achieve statewide protections from unrestricted LPR use.

First, state lawmakers must pass comprehensive LPR legislation. H.3755 strikes the right balance, protecting civil rights and civil liberties while allowing police to use LPRs for legitimate investigations. The bill prohibits law enforcement from using LPRs to monitor individuals based on First Amendment-protected activities, including political protests or religious gatherings. It requires that LPR data be deleted within 14 days unless a record is tied to a specific, ongoing criminal investigation supported by articulable facts. Access to LPR data would be limited to law enforcement for investigative purposes and could not be disclosed outside judicial proceedings. The bill also prohibits buying, selling, renting, or sharing LPR and related location data unless required by judicial process, and bars law enforcement from accessing LPR data collected by another entity without a valid search warrant. These provisions prevent the accumulation and sharing of data on millions of people not suspected of any wrongdoing, while allowing law enforcement to use LPRs in legitimate criminal investigations. This legislation would ensure consistent protections apply for all Massachusetts residents.

Second, police departments must take immediate action. Individual departments should stop voluntarily sharing data with out-of-state and federal agencies. They should redraft contracts with Flock to ensure their department retains full control of all data they collect. Finally, police departments must adopt internal policies requiring that every Flock network search be justified by a specific, documented reason for the inquiry, clarifying to all officers and staff that a non-descriptive entry like “investigation” will not suffice.

Take Action

Right now, your movements on Massachusetts roads are being tracked and shared with thousands of agencies nationwide. No warrant, no suspicion, no safeguards.

Join us in calling on the Massachusetts Legislature to pass common sense checks and balances on police use of license plate readers, to ensure that you retain basic civil liberties on the road.

Email your state legislators today to show your support for H.3755, An Act Establishing Driver Privacy Protections.

This post was updated on February 26, 2026, to reflect that more than 80 police departments across Massachusetts have contracts with Flock Safety.

Eyes in the Sky: Big Brother is (still) watching

New records obtained from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in December 2023 show that the number of drones licensed by government agencies has gone up across the Commonwealth. We’ve updated our interactive tool, which lets anyone explore the dataset and identify drones owned by public entities in their communities.

Search Government Drones in Massachusetts

Keep reading to see what we learned.

In 2021, we published a report detailing data acquired by the ACLU on government agencies’ use of drones in Massachusetts. According to late 2023 data, it remains the case that almost half (43%) of active government drones in Massachusetts are registered to police departments. The Massachusetts State Police has the largest number of drones of any police agency in the state.

In 2022, we published documents revealing police used drones to monitor Black Lives Matter protests in five cities in Massachusetts, including Boston. Video feeds from these drones were streamed in real-time to local police departments and the State Police “Commonwealth Fusion Center,” which shares information with federal agencies and out-of-state police entities.

Protecting public safety?

One of the most common drones registered by government agencies is the DJI Matrice line. Just one of these drones costs between $10,000 to $20,000 dollars. With 133 Matrice drones in operation in Massachusetts as of 2023, these drones alone likely cost taxpayers $1 to 2 million dollars.

Despite the hefty price tag, DJI drones – especially the Matrice and Mavic lines – have been prone to crashes. In August 2022, a police-operated DJI Mavic 2 Enterprise drone used to locate a suspect in the UK crashed into a building after its battery failed and it plummeted 130 feet. According to FAA documents, the Massachusetts State Police has registered eight DJI Mavic 2 Enterprise drones.

The DJI Matrice 210 drone is even less reliable. Reports of crashes were frequent enough that, in June 2020, the website www.reportdroneaccident.com urged Matrice 210 pilots to “not fly over any people,” echoing a warning from the drone manufacturer from 2018. Regarding the Matrice 210, a FAA-certified pilot and drone expert with the Wake Forest Fire Department reported in 2018 that “three public safety agencies … had batteries fail in flight.” In 2020, a Matrice 210 failed at 270 feet, crashing hard enough that a piece of the drone ended up “buried 8 inches deep.” Based on the DROPS standards, if a Matrice 210 drone were to fall on someone from just six feet or more, the injury would be fatal.

These crashes are not due to pilot error but rather stem from known issues with the technology itself. Despite these problems, as of December 2023, Massachusetts government agencies had 58 active Matrice 210 drones.

More drones, more money, more problems

The December 2023 FAA data shows that across Massachusetts, the total number of drones registered by government agencies increased by 169 between 2021 and 2023. The Massachusetts State Police acquired 19 additional drones, amounting to a 25% increase in the department’s drone fleet. Likewise, the Norfolk County Sheriff’s Department, which had a single drone in 2021, had acquired 19 more drones by 2023. Four of these new drones were the Mavic 2 Enterprise drones, discussed above.

Two years ago, we raised concerns that government entities, particularly police departments, were not doing enough to prevent the misuse of drones or drone footage. In 2022, Worcester City Council approved a request by the Worcester Police to purchase a $25,000 drone. The police department had come under fire from homeless advocates for using a drone to monitor people at encampments.

While Massachusetts has no laws on the books regulating police use of drones, the ACLU of Massachusetts supports legislation that would ban the weaponization of drones and other robots.

Search government drones in Massachusetts

If you want to look at the data yourself, you can use our interactive tool, where you can explore the data or download the data in full.

Search Government Drones in MassachusettsIf you’re interested in learning more about how government agencies in Massachusetts use drones, you can use our model public records request to find out. More information about this process and relevant resources are available here.

Boston Police Records Show Nearly 70 Percent of ShotSpotter Alerts Led to Dead Ends

Image credit: Sketch illustration by Inna Lugovyh

The ACLU of Massachusetts has acquired over 1,300 documents detailing the use of ShotSpotter by the Boston Police Department from 2020 to 2022. These public records shed light for the first time on how this controversial technology is deployed in Boston.

ShotSpotter — now SoundThinking — is a for-profit technology company that uses microphones, algorithmic assessments, and human analysts to record audio and attempt to identify potential gunshots. A public records document from 2014 describes a deployment process that considers locations for microphones including government buildings, housing authorities, schools, private buildings and utility poles.

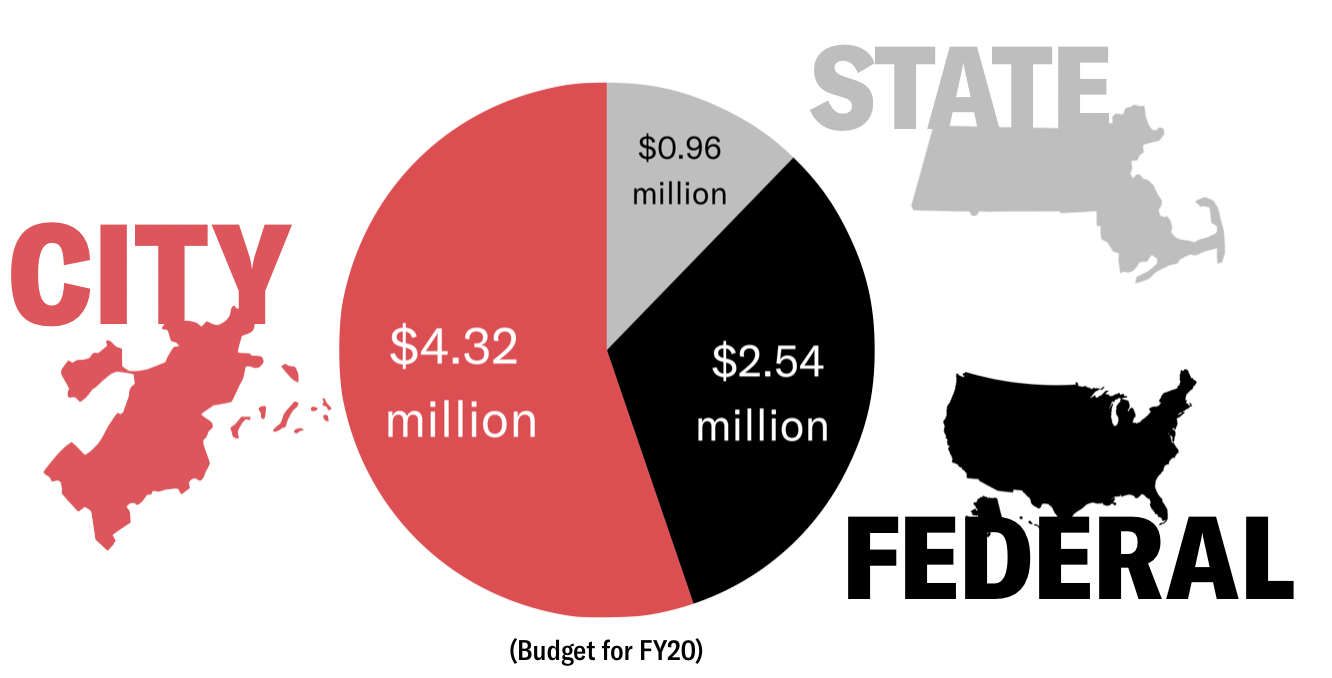

According to city records, Boston has spent over $4 million on ShotSpotter since 2012, deploying the technology mostly in communities of color. Despite the hefty price tag, in nearly 70 percent of ShotSpotter alerts, police found no evidence of gunfire. The records indicate that over 10 percent of ShotSpotter alerts flagged fireworks, not weapons discharges.

The records add more evidence to support what researchers and government investigators have found in other cities: ShotSpotter is unreliable, ineffective, and a danger to civil rights and civil liberties. It’s time to end Boston’s relationship with ShotSpotter. Boston’s ShotSpotter contract expires in June, making now the pivotal moment to stop wasting millions on this ineffective technology.

The records add more evidence to support what researchers and government investigators have found in other cities: ShotSpotter is unreliable, ineffective, and a danger to civil rights and civil liberties. It’s time to end Boston’s relationship with ShotSpotter. Boston’s ShotSpotter contract expires in June, making now the pivotal moment to stop wasting millions on this ineffective technology.

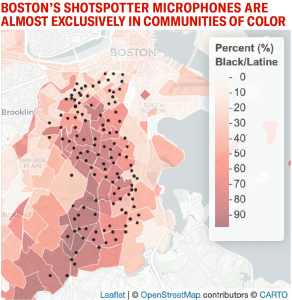

Boston’s relationship with ShotSpotter dates from 2007. A recent leak of ShotSpotter locations confirms ShotSpotter is deployed almost exclusively in communities of color. In Boston, ShotSpotter microphones are installed primarily in Dorchester and Roxbury, in areas where some neighborhoods are over 90 percent Black and/or Latine.

Coupled with the high error rate of the system, BPD records indicate that ShotSpotter perpetuates the over-policing of communities of color, encouraging police to comb through neighborhoods and interrogate residents in response to what often turn out to be false alarms.

For each instance of potential gunfire, ShotSpotter makes an initial algorithmic assessment (gunshot, fireworks, other) and sends the audio file to a team of human analysts, who make their own prediction about whether it is definitely, possibly, or not gunfire. These analysts use heuristics like whether the audio waveform looks like “a sideways Christmas tree” and if there is “100% certainty of gunfire in the reviewer’s mind.”

ShotSpotter relies heavily on these human analysts to correct ShotSpotter predictions; an internal document estimates that human workers overrule around 10 percent of the company’s algorithmic assessments. The remaining alerts comprise the reports we received: cases in which police officers were dispatched to investigate sounds ShotSpotter identified as gunfire. But the records show that in most cases, dispatched police officers did not recover evidence of shots fired.

Analyzing over 1,300 police reports, we found that almost 70 percent of ShotSpotter alerts returned no evidence of shots fired.

In all, 16 percent of alerts corresponded to common urban sounds: fireworks, balloons, vehicles backfiring, garbage trucks and construction. Over 1 in 10 ShotSpotter alerts in Boston were just fireworks, despite a “fireworks suppression mode” that ShotSpotter implements on major holidays.

ShotSpotter markets its technology as a “gunshot detection algorithm,” but these records indicate that it struggles to reliably and accurately perform that central task. Indeed, email metadata we received from the BPD describe several emails that seem to refer to inaccurate ShotSpotter readings. The records confirm what public officials and independent researchers have reported about the technology’s use in communities across the country. For example, in 2018, Fall River Police abandoned ShotSpotter, saying it didn’t “justify the cost.” In recent years, many communities in the United States have either declined to adopt ShotSpotter after unimpressive pilots or elected to stop using the technology altogether.

Coupled with reports from other communities, these new BPD records indicate that ShotSpotter is a waste of money. But it’s worse than just missed opportunities and poor resource allocation. In the nearly 70 percent of cases where ShotSpotter sent an alert but police found no evidence of gunfire, residents of mostly Black and brown communities were confronted by police officers looking for shooters who may not have existed, creating potentially dangerous situations for residents and heightening tension in an otherwise peaceful environment.

Just this February, a Chicago police officer responding to a ShotSpotter alert fired his gun at a teenage boy who was lighting fireworks. Luckily, the boy was not physically harmed. Tragically, 13-year-old Chicago resident Adam Toledo was not so fortunate; he was killed when Chicago police officers responded to a ShotSpotter alert in 2021. The resulting community outrage led Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson to campaign on the promise of ending ShotSpotter. This year, Mayor Johnson followed through on that promise by announcing Chicago would not extend its ShotSpotter contract.

The most dangerous outcome of a false ShotSpotter alert is a police shooting. But over the years, ShotSpotter alerts have also contributed to wrongful arrests and increased police stops, almost exclusively in Black and brown neighborhoods. BPD records — detailing incidents from 2020-2022 — include several cases where people in the vicinity of an alert were stopped, searched, or cited — just because they happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

For instance, in 2021, someone driving in the vicinity of a ShotSpotter alert was pulled over and cited for an “expired registration, excessive window tint, and failure to display a front license plate.” Since ShotSpotter devices in Boston are predominately located in Black and brown neighborhoods, its alerts increase the funneling of police into those neighborhoods, even when there is no evidence of a shooting. This dynamic exacerbates the cycle of over-policing of communities of color and increases mistrust towards police among groups of people who are disproportionately stopped and searched.

This dynamic can lead to grave civil rights harms. In Chicago, a 65-year-old grandfather was charged with murder after he was pulled over in the area of a ShotSpotter alert. The charges were eventually dismissed, but only after he had already spent a year in jail.

In summary, our findings add to the large and growing body of research that all comes to the same conclusion: ShotSpotter is an unreliable technology that poses a substantial threat to civil rights and civil liberties, almost exclusively for the Black and brown people who live in the neighborhoods subject to its ongoing surveillance.

Since 2012, Boston has spent over $4 million on ShotSpotter. But BPD records indicate that, more often than not, police find no evidence of gunfire — wasting officer time looking for witness corroboration and ballistics evidence of gunfire they never find. The true cost of ShotSpotter goes beyond just dollars and cents and wasted officer time. ShotSpotter has real human costs for civil rights and liberties, public safety, and community-police relationships.

For these and other reasons, cities including Canton, OH, Charlotte, NC, Dayton, OH, Durham, NC, Fall River, MA, and San Antonio, TX have decided to end the use of this controversial technology. In San Diego, CA, after a campaign by residents to end the use of ShotSpotter, officials let the contract lapse. And cities like Atlanta, GA and Portland, OR tested the system but decided it wasn’t worth it.

From coast to coast, cities across the country have wised up about ShotSpotter. The company appears to have taken notice of the trend, and in 2023 spent $26.9 million on “sales and marketing”. But the cities that have decided not to partner with the company are right: Community safety shouldn’t rely on unproven surveillance that threatens civil rights. Boston’s ShotSpotter contract is up for renewal in June. To advance racial justice, effective anti-violence investments, and civil rights and civil liberties, it’s time for Boston to drop ShotSpotter.

An earlier version of this post stated that one of the false alerts was due to a piñata. That was incorrect.

Further reading

- WIRED article on the “Secret Locations of ShotSpotter Gunfire Sensors”

- Chicago Office of Inspector General report

- MacArthur Justice Center study

- Longitudinal study on whether ShotSpotter reduces gun violence

- National ShotSpotter coalition website

Emiliano Falcon-Morano contributed to the research for this post. With thanks to Kade Crockford for comments and Tarak Shah from HRDAG for technical advice.

Yes, All Location Data: Separating fact from myth in industry talking points about “anonymous” location data

Image credit: Joahna Kuiper / Better Images of AI / Little data houses (square) / CC-BY 4.0

We carry our phones around wherever we go – and our cellphone location data follows us every moment along the way, revealing the most sensitive and intimate things about us. Everywhere we go, everyone we meet, and everything we do – it’s all accessible to anyone with a credit card, thanks to the data broker industry.

Apps use location data for a variety of purposes including finding directions, logging runs, ordering food, and hailing rideshares. While this information can be used for legitimate purposes, this sensitive data is also exploited for profit and extremist agendas, putting every cellphone user at risk. In 2023, right-wing extremists capitalized on the unregulated open data marketplace to out gay Catholic priests. This disturbing undertaking was possible because data brokers are allowed to buy location information, repackage it, and sell it to anyone who wants to buy it. And, currently, there’s nothing stopping them.

As independent researchers have shown time and time again, it is all too easy to trace cellphone location data back to the people holding those phones.

Data generated from apps are superficially ‘pseudo-anonymized’ by assigning each user a unique combination of numbers called a MAID (“Mobile Advertising ID”), also known as an IDFA (“ID For Advertisers”). But since each MAID is associated with a single device and common across apps, it’s easy to paint a unique picture of someone by aggregating location datapoints across apps.

In fact, just a few data points are sufficient to uniquely identify most individuals. Several highly-cited scientific studies using real-world cellphone location data – including a Scientific Reports research paper – showed that a few linked spatiotemporal data points are enough to uniquely identify most individuals from a crowd. Intuitively, if someone finds out where your phone is between midnight and five a.m., then they know where you likely live. If they then find out where your phone is between nine a.m. and five p.m. on weekdays, then they know where you likely work.

While two location points – home and work – are plenty, data brokers have much more data than that. In fact, data brokers peddle a sprawling digital dossier on millions of people with incredible temporal and spatial detail.

Recently, data broker Kochava was thrown into the spotlight as a result of a shocking investigation by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Among other revelations, analysts from the FTC were able to obtain a free sample of cellphone location data and use that information to track someone who visited an abortion clinic all the way back to their home. This data, like all data from data brokers, was supposed to be anonymous – instead, it revealed a person’s private health care practices and real identity. For vulnerable people travelling from states where reproductive health care is now a crime, the open sale of their cellphone location data is a serious matter. But Kochava is not a lone bad apple. They are one company out of a multibillion dollar industry that exists solely to profit off our data, putting us – and our loved ones – at risk.

Just in case location information is not sufficient to identify someone, it is easy to connect this data with other pieces of information that are easily accessible, such as a person’s public work directory, LinkedIn profile, or by using one of many people search sites that list people’s full names and addresses. Indeed, a spinoff industry has cropped up that offers “identity resolution” services to do just that. For instance, a company called Liveramp partners with several well-known location data brokers, claiming to “resolve data to the user or household level”, helping ad companies “build, configure, and maintain a unified view of your customer, easily connecting customer data from any and all data sources.” Similarly, data brokers like Adobe and Oracle offer identity resolution services to aggregate data across disparate data sources.

Mobile advertising IDs, as mentioned above, are part of the problem – but not the end of the road. In 2021, Google made some strides to secure MAIDs – but left opting out to more tech-savvy users. Meanwhile, Apple phased out MAIDs for users who don’t explicitly opt in to tracking. While these moves were a step in the right direction, they still leave a lot of room for loopholes. From consent for cookies to Do Not Track requests, the ad industry has historically countered every superficial privacy win with dogged – and successful – efforts to circumvent restrictions. When it comes to the “end” of MAIDs, the ad industry has already developed workarounds, allowing companies to match location data to users using “identity graphs”, even if they lack advertising IDs for those people.

As an executive of ad tech company himself described, “when you move to these more restrictive methods, what happens is that all the shady companies … try to find alternative workarounds to the MAID but with methods the user doesn’t have any control over, ultimately hurting end-user privacy.”

Data brokers claim they want to protect our privacy as much as we do. But we can’t trust that they will choose our privacy over their profits. We need more than superficial solutions.

That’s why the ACLU of Massachusetts and our partners are working to pass legislation to ban the sale of cellphone location data. This bill would prevent location data being tracked or traded for anyone in the state of Massachusetts. It is a vital defense to stop this multibillion-dollar industry from profiting from our personal data. We can’t do this without your help – so click here to contact your legislator and urge them to pass this crucial legislation. It’s time to end this shady practice once and for all.

Essential reading

- I Gave a Bounty Hunter $300. Then He Located Our Phone (Jan. 8. 2019). Joseph Cox, Motherboard. https://www.vice.com/en/article/nepxbz/i-gave-a-bounty-hunter-300-dollars-located-phone-microbilt-zumigo-tmobile

- Twelve Million Phones, One Dataset, Zero Privacy (December 19, 2019). Stuart A. Thompson and Charlie Warzel, New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/19/opinion/location-tracking-cell-phone.html

- We Spied on Trump’s ‘Southern White House’ From Our Couches (November 27, 2023). Aram Sinnreich and Jesse Gilbert, Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/data-brokers-trump-tech-spying-privacy-threat-1234897098/

- Debunking the Myth of “Anonymous” Data (November 10, 2023). Paige Collings, Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/11/debunking-myth-anonymous-data

- Catholic group spent millions on app data that tracked gay priests (March 9, 2023). Michelle Boorstein and Heather Kelly, Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2023/03/09/catholics-gay-priests-grindr-data-bishops/

- Unique in the crowd: The privacy bounds of human mobility (2013). Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye, César A. Hidalgo, Michel Verleysen and Vincent D. Blondel, Scientific Reports. https://www.nature.com/articles/srep01376

Eyes in the Sky: Massachusetts State Police Used Drones to Monitor Black Lives Matter Protests

Records obtained by the ACLU of Massachusetts reveal the State Police routinely fly drones over the Commonwealth, for a variety of purposes, without warrants.

During the summer of 2020, as the nationwide movement against systemic racism grew in the wake of the police murder of George Floyd, the State Police here in Massachusetts (MSP) were busy sending drones to quietly monitor Black Lives Matter protesters across the state.

Records obtained by the ACLU of Massachusetts show the MSP used aerial surveillance to track protests occurring in Fitchburg, Leominster, Gardner, Worcester, Agawam, and Boston. While internal police reports say police did not (in most cases) retain pictures or videos of the protests, the video feeds were streamed in real time to local police departments and the State Police Fusion Center for “situational awareness.”

The records also reveal that the MSP has participated in trainings facilitated by Dave Grossman, a former Army Ranger turned police trainer who has faced extensive criticism for his violent rhetoric. Grossman is infamous for teaching police what he calls “killology,” a so-called “warrior mindset” for officers.

Records obtained by the ACLU last year from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) show drones are in use by police departments across the state. Unlike other aerial surveillance technologies such as helicopters and spy planes, drones are easy to deploy, cheap, small, and quiet to operate. According to FAA records, the MSP owns 81 drones—making its program the largest law enforcement drone operation in the state.

The ACLU of Massachusetts filed several public records requests to understand how the MSP uses drones. In response to a request asking for records about drone use since 2020, the MSP told us there were almost 200,000 relevant records. Unfortunately, the MSP asked us to pay for most of them, amounting to a sum we could not afford. After negotiating with the agency, we agreed to narrow our request in the following way. We asked for (i) emails and reports for the time period between May 29, 2020 to June 15, 2020 and (ii) additional reports for the period between January 20, 2022 to May 24, 2022. This resulted in the disclosure of hundreds—instead of hundreds of thousands—of pages of documents. What we obtained therefore only opens a small window onto the MSP’s drone program, but the records nonetheless provide important information about how the MSP uses their drones.

How did the MSP acquire a drone fleet?

According to the records, as of October 2022, the department had 22 drones, including the following makes and models:

- Four Mavic 2 Hasselblads

- Three Mavic 2 Enterprise Duals

- Two Sparks

- Three Matrice 300 RTKs

- Eight Mavic Minis

- One Phantom 4 Pro+

The two most advanced drones are the Mavic 2 Enterprise Dual and the Matrice 300 RTK.

- The Mavic 2 Enterprise Dual: This powerful drone has thermal imagery capabilities, an integrated radiometric thermal sensor, adjustable parameters for emissivity and reflective surfaces, and multiple display modes.

- The Matrice 300 RTK: This is also a very advanced model—at the time of writing, the latest one released by the manufacturer DJI—offering up to 55 minutes of flight time, machine learning technology that recognizes a subject of interest and identifies it in subsequent automated missions to ensure consistent framing, six directional sensing and positioning, and 15km-1080p map transmission.

The records show the federal government financed the expansion of the MSP drone program, with the state government as an intermediary. In 2019, the MSP received an award of $99,011 from the state government to purchase drones. The funding came from the Homeland Security Grant Program, a Department of Homeland Security funding stream available to all states. This federal funding, passed through the state, allowed the State Police to purchase nine drones from a company called Safeware.

The MSP’s drone policy

The MSP also produced a policy to govern the department’s use of drones. The policy includes some important civil rights protections, but needs substantial work. And crucially, an ACLU review of records provided by the MSP indicates the department’s compliance with the policy appears to be inconsistent.

The policy establishes that drones may be used for a list of purposes that is far too broad, leaving the door open to abuse and misuse. The policy should explicitly list all permissible purposes for drone use. Instead, it takes an open-ended approach. For example, the records show “Homeland Security” is listed as a permissible purpose for drone usage. But this vague phrase is open to extremely broad interpretation, and could be used to justify drone usage in almost any scenario.

The policy states that the drone program is operated by the Unmanned Aerial Section of the Homeland Security and Preparedness division of the MSP. But “Homeland Security” has nothing to do with the vast majority of enumerated purposes listed in the policy, such as accident reconstruction, missing persons investigations, and criminal investigations surveillance. It is likely that the “Homeland Security” division is in charge of the drone program simply because the money for most of the drones came from the federal DHS, not because the drones are actually used in operations relative to “homeland security” operations.

The policy requires police to obtain a warrant or court order to use a drone in a criminal investigation, where a person has a reasonable expectation of privacy (except in exigent circumstances). However, in response to our requests, the MSP did not produce a single search warrant, indicating that the department has never obtained one to use a drone for surveillance purposes. There could be several reasons for this. It’s possible that police are: 1)simply not using drones in criminal investigations, 2) using them without a warrant in violation of the policy, 3) defining “reasonable expectation of privacy” too narrowly, or 4) simply using drones only to investigate criminal activity when exigent circumstances make getting a warrant impractical. Regardless, the fact that the MSP has never once obtained a warrant to use a drone indicates that the policy does not offer sufficient privacy protection. This suggests that we need a law on the books to enforce our rights.

Current privacy protections are not enough

To the MSP’s credit, their policy incorporates the principle of data minimization. This means that in order for any data to be collected with a drone, that data must be essential to complete the objective of the drone mission. Additionally, the policy states that drones cannot be paired with facial recognition technology to identify individuals in real time, and may not be used to carry weapons or facilitate the use of any weapons and/or dispersal payloads. These are important protections, and the ACLU applauds the MSP for including them.

That said, other language in the policy meant to protect civil rights and civil liberties is weak. For example, the policy forbids police from using a drone to target a person based solely on individual characteristics such as race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, disability, gender, or sexual orientation. But the inclusion of the word “solely” leaves open the possibility that the police will target someone in part on the basis of a protected characteristic like their race or national origin.

Likewise, the policy forbids the collection, use, retention, or dissemination of data in any manner that would violate the First Amendment or in any manner that would unlawfully discriminate against persons based upon their ethnicity, race, gender, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, or gender identity. But case law is underdeveloped and insufficient in these areas, leaving decision making about what constitutes a First Amendment violation or discrimination up to the police. Instead, the language should clearly stipulate that the MSP shall not use drones to monitor people exercising their First Amendment rights to assemble, petition the government, exercise their religion, or protest.

Instead, the policy allows drone footage to be collected, processed, used, and shared in a broad range of situations that threaten core civil rights and civil liberties. And this is exactly what’s happened, such as when the MSP, in partnership with local police, used drones to surveil Black Lives Matter protests across the state. Under the guise of “crowd control, traffic incident management, and temporary perimeter security,” the MSP was actively surveilling people exercising their First Amendment rights. The MSP should strengthen their policy to prohibit the collection and processing of drone information concerning First Amendment expression.

Finally, the policy is silent on a critical issue: data sharing. As a result, we do not know who has access to drone footage collected by the MSP, under what circumstances, or subject to what type of request. The lack of any information about data sharing is particularly concerning given the involvement of the Commonwealth Fusion Center in the drone program.

How has the MSP used drones?

While the policy sets out how drones ought to be used, emails, communications, and reports show how the MSP actually uses its drones. To that end, we obtained drone flight logs covering the period between January and May 2022. Generally, those records show that drones were mostly used in the following places:

You can access an interactive map here.

Municipalities where the Mass State Police conducted drone flights between January 1 and May 24, 2022

The records show that the MSP used drones for the following purposes during this time period:

- Monitoring Black Lives Matter protests and rallies in Fitchburg, Leominster, Gardner, Worcester, Agawam, and Boston;

- In criminal investigations, for example an attempt to locate evidence related to a New Hampshire State Police investigation (the MSP found no evidence);

- Finding missing persons;

- Mapping accident scenes;

- Mapping airports;

- Transit purposes;

- Investigating the operation of private drones; and

- Training and mapping exercises.

Note that the category “Search & Rescue” includes missions ranging from searching for missing persons to searching for suspects in criminal investigations. Of the 25 flights labeled “Search & Rescue,” at least 7 are related to criminal investigations or searches for suspects, and 18 related to missions looking for missing persons such as elderly people or people with mental health issues. These are very different kinds of missions, and the MSP should group them into different categories in order to facilitate greater transparency and accountability.

Learning more about government use of drones in Massachusetts

The records published here provide a glimpse into drone use at the MSP. But the MSP is not alone—many other police departments across the state use drones. During the summer of 2022, the Public Safety Subcommittee of Worcester City Council was the stage for a public outcry when community members expressed their concerns about the police department’s proposal to acquire drones. The Boston Police Department also has a large drone program.

If you’re interested in learning more about how government agencies in Massachusetts use drones, you can use our model public records request to find out. More information about this process and resources are available through the tool linked below.

If you find anything interesting, please contact us at data4justice@aclum.org.

Break Up with the BRIC: Unpacking the Boston Regional Intelligence Center Budget

Explore all of the ACLU of Massachusetts' analysis on policing in the Commonwealth.

On Thursday, July 23, the Boston City Council is holding a hearing on three grants that would collectively approve over $1 million in additional funding to the Boston Police. These taxpayer dollars would go towards installing new surveillance cameras across Boston and funds for the Boston Regional Intelligence Center, or BRIC.

Thursday’s hearing is a re-run from a routine hearing which took place on June 4, in which the Boston City Council was slated to rubber-stamp these three grants - dockets #0408, #0710, and #0831. However, community advocate groups such as the Muslim Justice League rallied, urging the Councilors to be critical of – and ultimately reject – the BPD grants. Ironically, the BRIC representative failed to make an appearance at the hearing and the question of the grant approval was tabled for this future date.

Out-of-control funding of the Boston Police is nothing new - as discussed in an ACLU of Massachusetts analysis, in FY21 the initially proposed Boston Police budget was $414 million. Ultimately, the Boston City Council still approved $402 million for the BPD, despite thousands of constituents advocating for more substantial budget cuts.

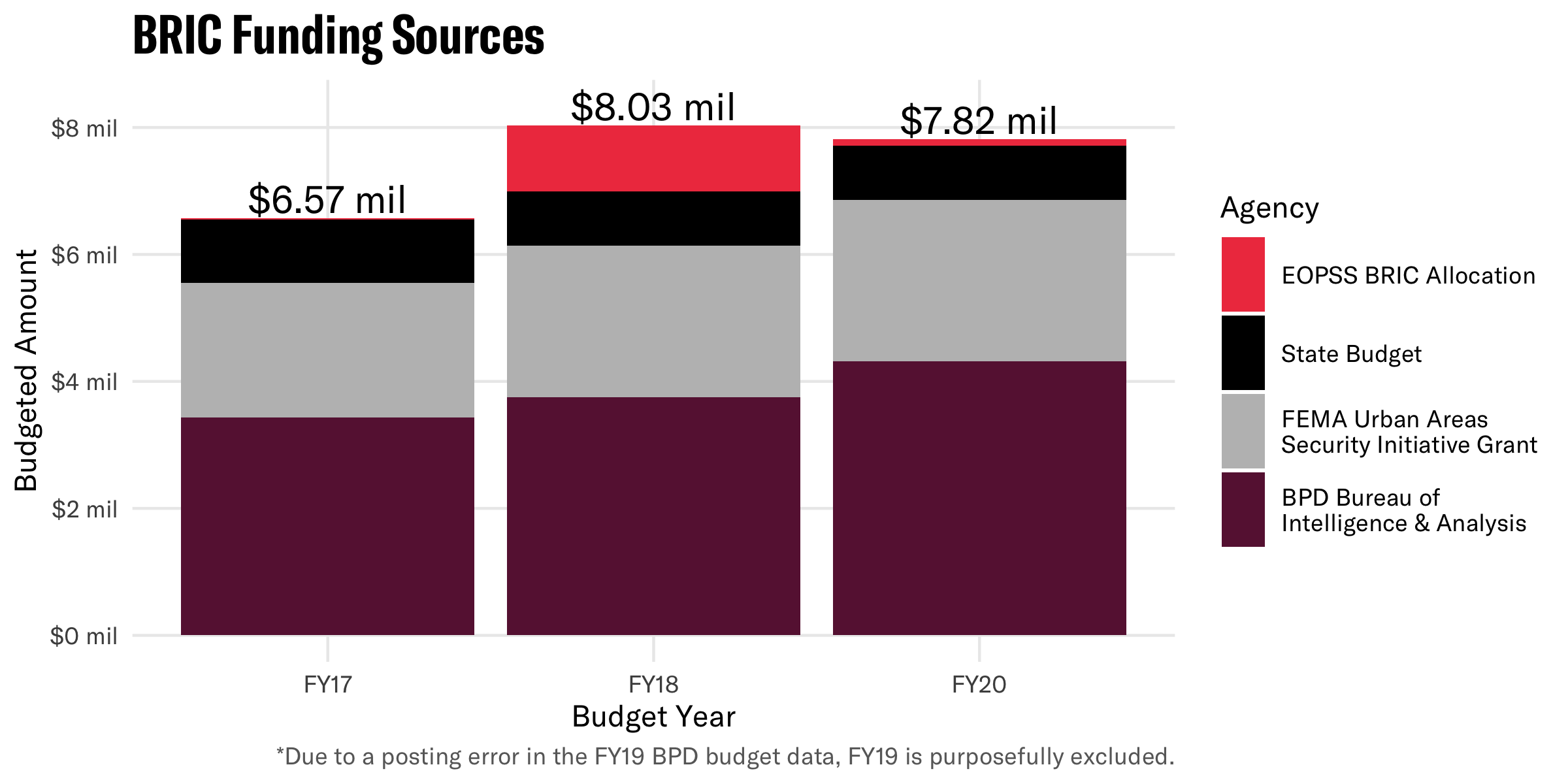

However, specific scrutiny of the BRIC and its funding is long overdue. In recent years, city, state, and federal legislatures have authorized well over $7 million in funding for the BRIC each year. But due to BPD secrecy surrounding all things BRIC-related, it’s hard to paint a full picture of what the BRIC does with this funding. Indeed, the description of the program on the Boston Police Department website consists of a mere 122 words - so we are forced to consult alternate sources and public records requests to get any details.

A new analysis of public records by the ACLU of Massachusetts takes a closer look at where the BRIC’s money comes from -- and what it’s used for.

What is the BRIC?

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is home to two federal fusion centers: Department of Homeland Security-funded centers established after September 11th, which facilitate information sharing between local, federal, and state law enforcement. One such center, the Commonwealth Fusion Center, is operated by the Massachusetts State Police, while the second, the Boston Regional Intelligence Center, or BRIC, is operated by the Boston Police Department.

The BRIC operates across the entire Metro Boston Homeland Security Region (MBHSR), which includes Boston, Brookline, Cambridge, Chelsea, Everett, Quincy, Revere, Somerville, and Winthrop.

Ample and Diverse Funding

According to public records obtained and compiled by the ACLU of Massachusetts, the BRIC is funded by a combination of federal, state, and local budgets and grants.

Specifically, the BRIC receives funding from at least four distinct sources:

- Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Urban Areas Security Initiative (UASI) grants

- Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety and Security (EOPSS) yearly allocations, most likely from the DHS FEMA State Homeland Security Grant program

- Massachusetts state budgets (passed through the Executive Office of Public Safety and Security (EOPSS); line item 8000-1001)

- City of Boston operating budgets (via the Boston Police Department’s Bureau of Intelligence & Analysis)

These four funding streams combined lead to the BRIC receiving approximately $7-8 million each year in public funds.

Note that correspondence with the City of Boston revealed that publicly available data for the FY19 BPD Bureau of Intelligence & Analysis budget is incorrect due to a “posting error”, and so FY19 is excluded from all figures.

Additionally, it’s important to note that due to the lack of transparency, these four sources might not encompass all of the funding coming into the BRIC. For instance, a FY21 report of BPD contracts shows $4 million in payments for “intelligence analysts” to Centra Technologies between 2018 and 2021, likely working at the BRIC. If so, the BRIC budget may indeed be millions of dollars greater than what we are able to report today.

Who’s on the payroll?

How many people do work for the BRIC – and get their salaries from its budgeted funds? Ten? Sixty? It’s difficult to know.

Expense reports reveal at least 41 employees received training from the BRIC between 2017 and 2019 - but 10 of these names do not appear on the City of Boston payroll for those years.

Records show that the BRIC has some dedicated employees: in FY20, the personnel budget for the BPD’s Bureau of Intelligence and Analysis - whose sole charge seems to be the management of the BRIC - was $4.3 million. And in 2019, BRIC expense reports show $1.8 million in payments towards contracted “Intelligence Analysts” through companies such as Centra Technology, The Computer Merchant, and Computer and Engineering Services, Inc. (now Trillium Technical). But would this $1.8 million support 7 analysts making $250k per year? 30 analysts at $60k? The records do not provide clarity on this point.

Finally, confusion around one of the grants being discussed at Thursday’s hearing, proposed in docket #0408, further epitomizes the BRIC’s financial obfuscation around its payroll. The docket formally proposes $850,000 in grant funding to go towards “technology and protocols.” However in discussion at the June 4 hearing it was revealed that, in actuality, part of the grant would go toward hiring 6 new analysts.

By keeping under wraps the roles and job titles of BRIC employees, and even simply the size of the Center, BRIC obstructs transparency, public accountability, and city council oversight.

Hardware and Software Galore

Between 2017 and 2020, BRIC expense reports show the Center spent almost $1.3 million on hardware and software. Thorough review of these reports reveals exorbitant spending: on software of all flavors, scary surveillance technologies, frivolous tech gadgets, and some obscure mysteries.

A number of the expenses are clearly for surveillance cameras and devices, including $106,700 in orders for “single pole concealment cameras”. These pole cameras were bought from Kel-Tech Tactical Concealments, LLC, a company which also supplied the BRIC with some truly dystopian concealment devices such as a “Cable splice boot concealment” ($10,900), a “ShopVac camera system” ($5,250), and a “Tissue box concealment” ($4,900). These purchases imply the BRIC is hiding cameras in tissue boxes, vacuum cleaners, and even electrical cables.

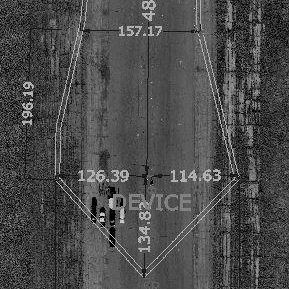

Some of the charges on the report are just too vague to interpret. This includes the largest hardware/software charge in the entire report: $164,199 paid to Carousel Industries for “BRIV A/V Upgrade per Bid Event”. There’s $36,997 in “Engineering Support”, paid to PJ Systems Inc. and $15,606 in a “C45529 CI Technologies Contrac[t]”, paid to CI Technologies. And concerningly, there is a cumulative $16,200 in charges described simply as “(1 Year) of Unlimited” paid to CovertTrack Group Inc. – a company which also supplied the BRIC with a “Stealth 4 Basic Tracking Devic[e]” to the tune of $7,054.

When it comes to computing hardware, there’s no skimping either. Reports show over $200,000 in expenses for servers, and over $67,000 for various laptops. And apparently the BRIC prefers Apple products - judging by the $10,000 they spent on iPad pros, almost $1,000 on Apple Pencils, and $367 on Apple TVs.

Yet the most indulgent spending is on software. Between 2017 and 2020, the BRIC purchased at least 13 specialized software products for intelligence analysis, crime tracking, public records access, device extraction, and more.

| Software | Use | BRIC Expenses 2017-2020 |

| IBM i2 | “Insight analysis” | $124,852 |

| CrimeView Dashboard | Crime analysis, mapping and reporting | $58,009 |

| Accurint | Public records searches | $32,803 |

| Esri Enterprise | Geospatial analysis | $27,000 |

| Thomson Reuters’ CLEAR | Public records searches | $25,322 |

| CrimNtel GIS | Crime analysis, mapping and reporting | $21,016 |

| Computer-Aided Dispatch (CAD) Interface | Emergency response | $16,387 |

| Cellebrite Universal Forensic Extraction Device (UFED) Ultimate 4PC | Device data extraction | $12,878 |

| CaseInfo | Case management | $10,508 |

| NearMap | Geospatial analysis | $9,995 |

| ViewCommander-NVR | Surveillance camera recording | $3,778 |

| eSpatial | Geospatial analysis | $3,650 |

| XRY Logical & Physical | Device data extraction | $2,981 |

And worse, there is redundancy between the products - the BRIC purchased three different geospatial analysis products, two public records search products, and two device data extraction products.

This smorgasbord of tools begs the question: What, if any, supervisory procedures exist within the BRIC to prevent irresponsible spending of taxpayer dollars on expensive, duplicative software?

And furthermore, some of these public records databases give users immense power to access residential, financial, communication, and familial data about almost any person in the country. So who, if anyone, oversees the use of powerful surveillance databases like Accurint and CLEAR, to ensure they aren’t being used to violate basic rights and spy on ex-girlfriends?

From a history of First Amendment violations in Boston, to their role in threatening local immigrant students with deportation, to a 2012 bipartisan Congressional report concluding fusion centers such as the BRIC have been unilaterally ineffective at preventing terrorism, there is much evidence in support of the BRIC being wholly defunded. But at the very least, the Boston City Council must end the practice of writing blank checks for the Boston Police to continue excessive and unscrutinized spending of taxpayer dollars.

The Boston City Council must reject the additional $1 million in funding to the Boston Police being proposed in these three grants. To learn more about the BRIC, the proposed grants, and to urge the City Council to reject them, we encourage you to:

- Consult the Muslim Justice League Toolkit to Get the BRIC Out of Boston

- Sign a petition telling Boston City Councilors to reject BRIC-related grants before Tuesday, July 28

- Submit written testimony for the BRIC budget hearing before 9:30 AM on Saturday, July 25, telling Boston City Councilors to reject BRIC-related grants

Boston City Council Hearing on Proposed Ordinance to Ban Face Surveillance

Boston City Council Hearing on Proposed Ordinance to Ban Face Surveillance

On June 9, 2020, the Boston City Council's Committee on Government Operations held a hearing to discuss Councilor Michelle Wu and Councilor Ricardo Arroyo's proposed ordinance to ban face surveillance in Boston's municipal government. Dozens of advocates, academics, and community members testified at the hearing.

Below is a sample of some of the written testimonies submitted in support of banning face surveillance in Boston.

Organizations

National Lawyers Guild - Massachusetts Chapter

Surveillance Technology Oversight Project

Boston Public Library Professional Staff Association

Electronic Frontier Foundation

Academics, advocates, and community members

Woodrow Hartzog and Evan Selinger