New to Data for Justice? Get caught up with our 2020 report on the Boston Police budget and other work on policing in Massachusetts.

Boston’s Acting Mayor Kim Janey just this week proposed a new budget for the coming fiscal year: one which maintains a slightly reduced allocation for police overtime. But as we look to the future of policing budgets, we still have much to learn from the past.

Last June, facing monumental pressure from local advocates and community members, the Boston City Council approved a City budget that “cut” the Boston Police Department’s gargantuan overtime allowance by 20 percent – from $60 million to $48 million. Not even a year later, that “cut” has been exposed as an empty promise.

On March 12, the Boston City council held its third quarterly hearing to follow up on how the BPD is reducing overtime costs. The update was bleak: just eight months into fiscal year 2021 (FY21), data show the BPD has already blown through almost the entirety of its $48 million overtime budget – setting itself up to finish out the fiscal year $20 million over budget.

This debacle has made one thing quite clear: when it comes to reining in police spending in Boston, the budget as defined by the City Council is effectively irrelevant. This is due to both (1) a century-old exception in the City Charter that writes the Police Department a blank check, and (2) the fact that many aspects of policing policy are tied up within police union contracts. So who is it that holds the power to actually affect change? TL;DR: it’s the mayor.

In a new analysis, the ACLU of Massachusetts dives deeper into the issue of overtime within the Boston Police Department and how the Mayor of Boston might be able to finally address it. We set out to answer the following questions:

- Just how big is the BPD’s FY21 overtime overage?

- Why does the City let police overtime spending go over budget at all?

- What factors contribute to overtime spending?

- How can we actually fix it?

Access and share this blog published in the form of a report here.

Just how big is the BPD’s FY21 overtime overage?

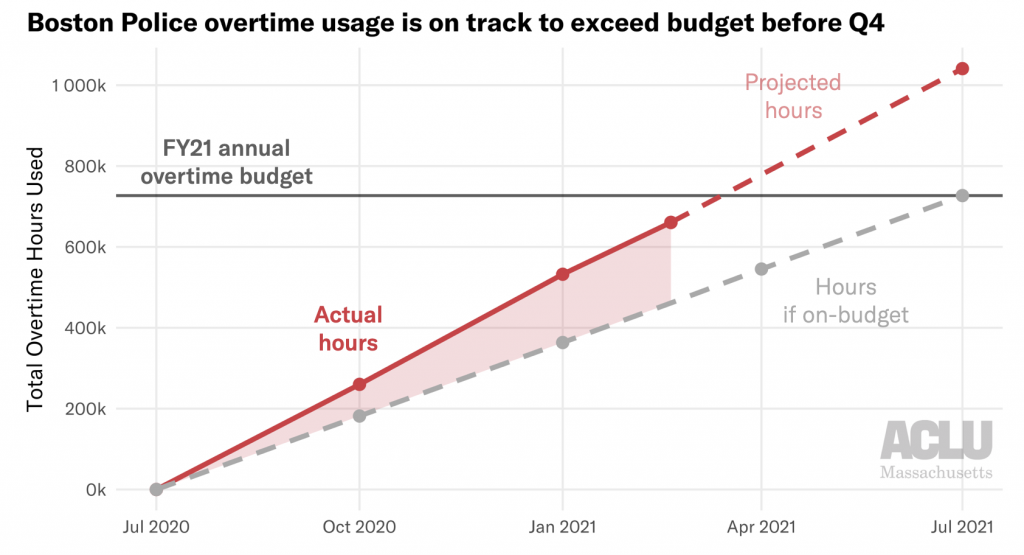

Since we are only three quarters of the way through FY21 (the fiscal year in Boston goes from July 1 through June 30), we can’t know how much the BPD will ultimately go over their overtime budget. However, current projections show an extreme overage, to the tune of more than 300,000 hours.

Indeed, if the current rate of overtime usage continues through the end of FY21, BPD will close out the year with a whopping 1 million overtime hours – 30 percent above the budgeted 727,000 hours. With an hourly overtime rate of approximately 66 dollars an hour, that overage translates to about $20 million of unbudgeted spending that the City will have to cough up. (The BPD itself predicts an overage of $15 million, but that would require a decrease in the rate of OT usage over the next three months – an unlikely outcome.)

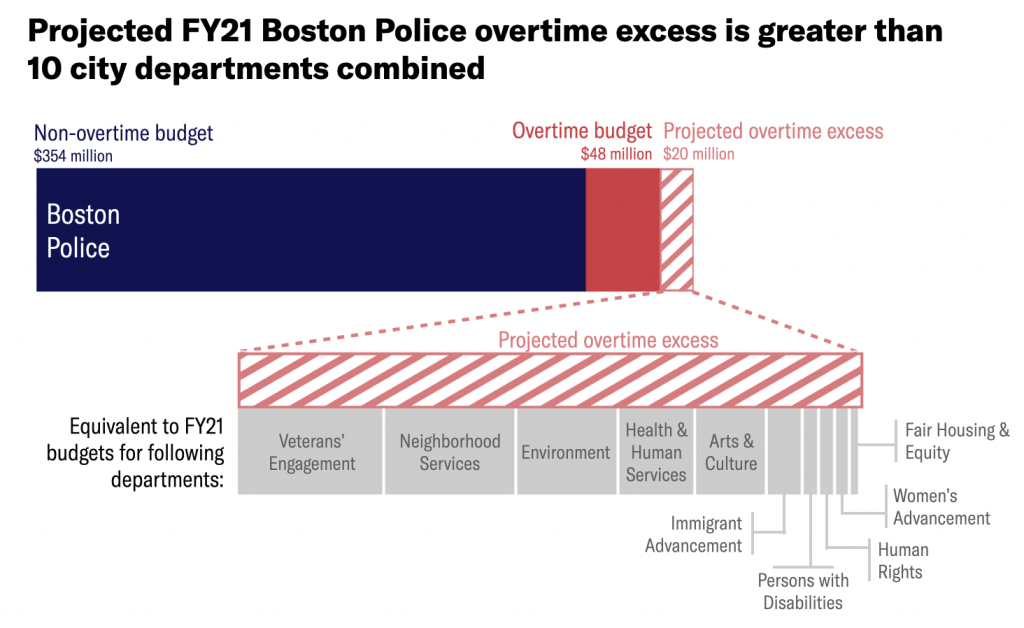

It’s hard to overstate how far these taxpayer dollars could go if they were put elsewhere. The projected $20 million excess is about half of the FY21 budget for the Library Department and is 8 times larger than the entire FY21 budget for the Office of Health & Human Services. Actually, the projected $20 million excess is larger than the FY21 budgets of the following 10 City departments combined:

- Veterans’ Engagement ($4.6 million)

- Neighborhood Services ($4.1 million)

- Environment ($3.2 million)

- Health & Human Services ($2.4 million)

- Arts & Culture ($2.2 million)

- Immigrant Advancement ($1.1 million)

- Human Rights ($500,000)

- Women’s Advancement ($460,000)

- Fair Housing & Equity ($320,000)

These numbers make it clear that the Boston Police Department is a budgetary parasite, aggressively hoarding taxpayer funds that are sorely needed by other City offices that provide support to communities.

So, how is it that the police are allowed to go over their budget so egregiously?

Why does the City let police overtime spending go over budget at all?

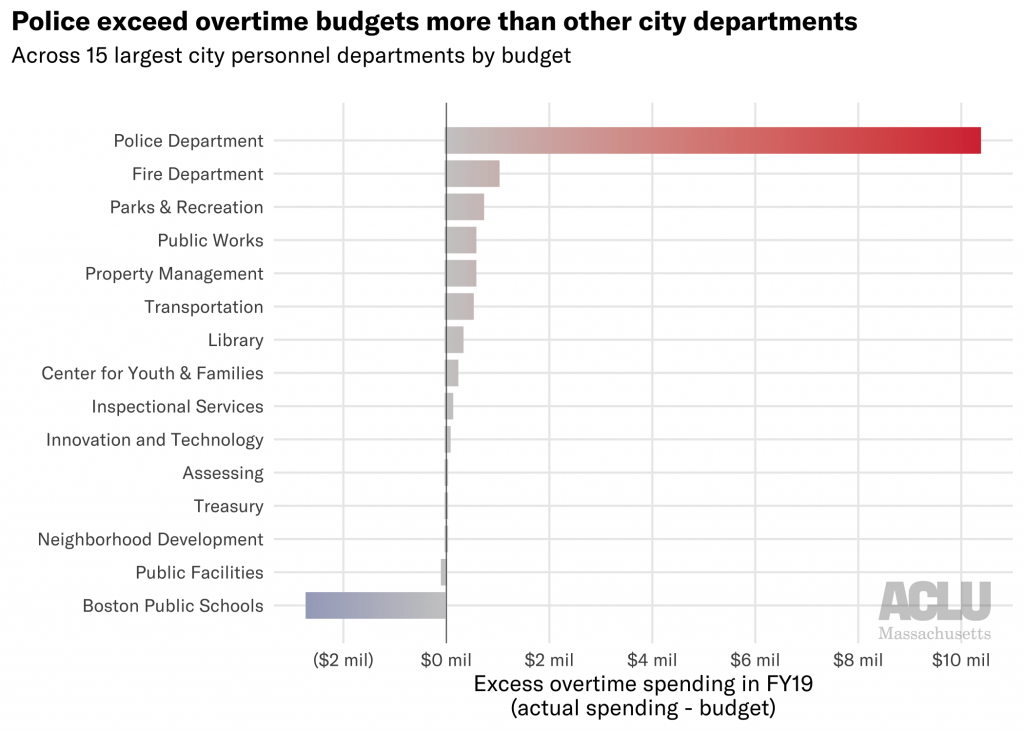

Historically, the Police Department has seen by far the largest overtime overages of any City department. In FY19, for instance, overtime spending went $10.4 million over budget. No other department came close:

And in comparison, the largest City department, Boston Public Schools, actually spent $2.7 million less on overtime than they were budgeted in FY19.

The City allows police overtime overages to happen because of a vague exception carved out of the City Charter, first included in 1909 and later amended in 1982. It states:

No official of said city, except in case of extreme emergency involving the health or safety of the people or their property, shall expend intentionally in any fiscal year any sum in excess of the appropriations duly made in accordance with law (Boston City Charter, section 42, emphasis added)

In practice this clause is interpreted by the City to mean, as stated by the Boston Municipal Research Board in their 2014 report, that “Police and Fire Department spending for emergency situations, snow removal costs and Execution of Court expenses from court decisions are legally allowed to exceed their appropriations.” No matter that Section 42 does not explicitly mention the Police Department.

Curiously, the above language could suggest that City offices which address public health crises, including COVID-19 and systemic racism, are also allowed to spend in excess of their budgets – but this is not how the Charter has historically been interpreted.

Effectively, the City has decided that all policing qualifies as an “extreme emergency,” and as such is not beholden to budgetary appropriations; police can use City funds with wild abandon without the fear of consequence that other departments face.

What factors contribute to overtime spending?

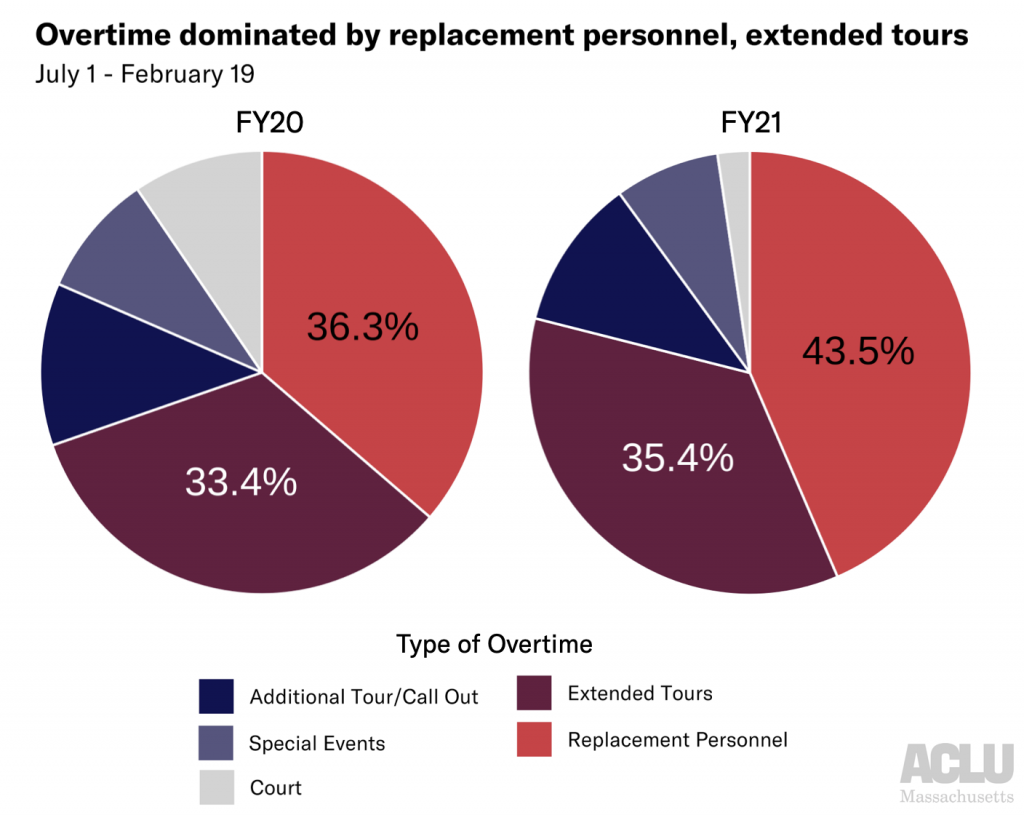

So where are all of these unfettered overtime funds going? Boston Police officers use various different sorts of overtime:

- Extended tours – when officers work longer than their assigned 8-hour shift

- Additional tours/call out – when officers are called in for unexpected additional shifts

- Court – when BPD officers visit a courthouse (dropping off documents, testifying, etc.) outside of their normal shift; results in a minimum 4 hours of overtime pay regardless of visit length

- Special events –when BPD officers establish a presence at specific events (e.g., parades, sporting events, elections) or certain situations (e.g. heavy police presence at Mass & Cass)

- Replacement – when officers sign up for extras shifts to cover officers who are out on sick leave, vacation, etc.

Replacing personnel and extending tours account for the vast majority of overtime hours – over 75 percent so far in FY21. It’s hard to know exactly why this is, as the police have provided multiple reasons including more officers out on sick leave due to COVID, an increase in retirements, and precautions taken around the 2020 election.

But different categories beg the fundamental question: what counts as “overtime”? Why aren’t officers’ schedules arranged such that court visits, annual parades, and longer shifts are included within normal shift scheduling, avoiding costly time-and-a-half overtime pay? Could it be the case that the “minimum staffing” standards that the Department establishes are inflated, requiring more officers than necessary to be on the street, and thus requiring more costly replacement personnel overtime than reasonably required? The BPD has sidestepped questions by the City Council about just these issues.

It’s also critical to ask how overtime policing specifically causes harm. Police presence at “special events” has resulted in the cops destroying wheelchairs, running over peaceful protestors (and later bragging about it on camera), and displacing poor and unhoused residents. As long as the City excuses such destructive behavior from the BPD, the cost of police overtime will always be more than just financial.

Careful consideration of such questions helps underscore that the solution to the overtime problem is not hiring more police officers. We aren’t in this overtime mess because Boston has too few cops; we’re in this mess because of toothless budgetary policies, decades of unsupervised policing practices, and an unrestricted power that police wield over their role in the City.

How can we actually fix it?

As the past eight months have exemplified, thanks to the carve-out in the City Charter, any police budget cuts approved by the City Council have no teeth. In addition, many of the policing-related ordinances that the Council is considering this session would be effectively powerless even if passed, because the policies they seek to change are concretized in police union contracts – such as policies defining shift scheduling, discipline, court overtime, 9-1-1 dispatch, and construction details.

Rather than the Council, the governmental body which currently has the power to actualize police budget reform is the Mayor. Specifically, the current budget can be changed based on (1) the Mayor’s priorities while renegotiating police association contracts, and (2) their interpretation of exceptions for police spending written into the City Charter.

We expect that many of the City’s largest police fraternities are now in the process of renegotiating their collective bargaining agreements after their expiration on June 30, 2020, including the Boston Police Patrolmen Association and the Boston Police Detectives Benevolent Society. (There is no way to know the status of new contracts because police association negotiations are not open to the public.) As demonstrated by their statements and actions, police fraternities are neither aligned with the broader labor movement nor are they concerned with public safety; their overreaching power must be reined in.

As such, Boston’s mayor must negotiate contracts that establish reasonable salaries and free up more aspects of policing policy to be under City, not police fraternity, control. Even better, the mayor should lift the veil of secrecy around such an important process: soliciting input from community leaders and advocates when determining priorities and lines in the sand for fraternity contracts, and clearly communicating those priorities to the public. Only then might the City Council pass progressive policing policies that have a shot at actually affecting change.

Additionally, there is reason to believe that of what constitutes an “extreme emergency” as stated in the City Charter might go far to re-establish accountability structures when the police, say, go seven figures over their allocated budget. The police will likely claim that everything they do qualifies as an “emergency,” but the City doesn’t have to agree. Modern policing in Boston includes much more than 9-1-1 dispatch and urgent responses to local events; overtime policing is not emergency response.

Excessive police spending in Boston is a budgetary octopus: there are many different arms thrashing about that contribute to the problem. Between disproportionate payroll increases resulting from extremely powerful police fraternities (i.e. arbitration awards), overly generous court appearance policies that pay police for time they don’t work, monopolization of private construction details, potential misuse of sick leave policies, and costly vacation buyback programs that boost pensions, it can be hard to know where to start.

When it comes to police overtime, the past year has been a long lesson in the danger of symbolic “changes” that ultimately leave the status quo untouched. Yet local advocacy groups like Muslim Justice League and Families for Justice as Healing have not quieted their calls to redistribute police funding back into communities. Their continuing pressure for more transparency has helped to illuminate the path forward.

We know what the next steps are: Acting Mayor Kim Janey, and every mayoral administration to come, must take a strong stance against egregious police spending: refusing to agree to exploitative police union contracts and putting a foot down over “emergency” budget excesses.

Data sources:

- Data on BPD OT usage presented at March 12 Boston City Council hearing

- Documents reporting Boston FY19 departmental OT budgets (listed in FY20 documents) and OT expenditures (listed in FY21 documents)

- Adopted Boston FY21 budget

This report and analysis was authored by Lauren Chambers (ACLUM) with the guidance of Kade Crockford and Rahsaan Hall (ACLUM) . The analysis also benefitted from crucial feedback and input from members of the Muslim Justice League and the Building Up People Not Prisons Coalition.