Data Show COVID-19 Out of Control Across Massachusetts Prisons and Jails

Four county facilities with over 80 confirmed COVID-19 cases. Multiple county jails conducting fewer than 100 COVID tests over nine months. A 10 percent increase in individuals jailed before trial across the state.

Yesterday, together with the Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS) and the Massachusetts Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (MACDL), the ACLU of Massachusetts filed an amended petition in their existing case with the Supreme Judicial Court seeking relief for individuals incarcerated in county facilities who are currently threatened by the spread of COVID-19 across the state.

Almost nine months have passed since ACLUM first filed this lawsuit in late March, asking the Court to recognize the elevated risk that the pandemic posed to individuals incarcerated in both county and state facilities and to decrease the population of carceral facilities across the state. The Court’s ruling recognized the necessity of decreasing the incarcerated population, and ordered jails and prisons throughout the state to regularly report their population, releases, COVID-19 tests and results.

While yesterday’s filing focuses solely on county facilities, the data reported by both county and state facilities since April raise significant concerns regarding COVID-19 in carceral settings throughout the state.

An interactive dashboard created and maintained by the ACLU of Massachusetts presents weekly data reported by 19 facilities run by 13 county sheriffs (jails and houses of correction or HOCs) and daily data from 16 state Department of Correction (DOC) prisons – 35 facilities in sum. Analysis from the first week of reporting in April already demonstrated an inadequate COVID response in prisons and jails that, unfortunately, has continued for the better part of a year. Indeed, in recent weeks, advocates, attorneys, and worried family members have witnessed frighteningly low test rates, followed by outbreaks in over a dozen facilities – and now, deaths. Here we present four takeaways from recent trends.

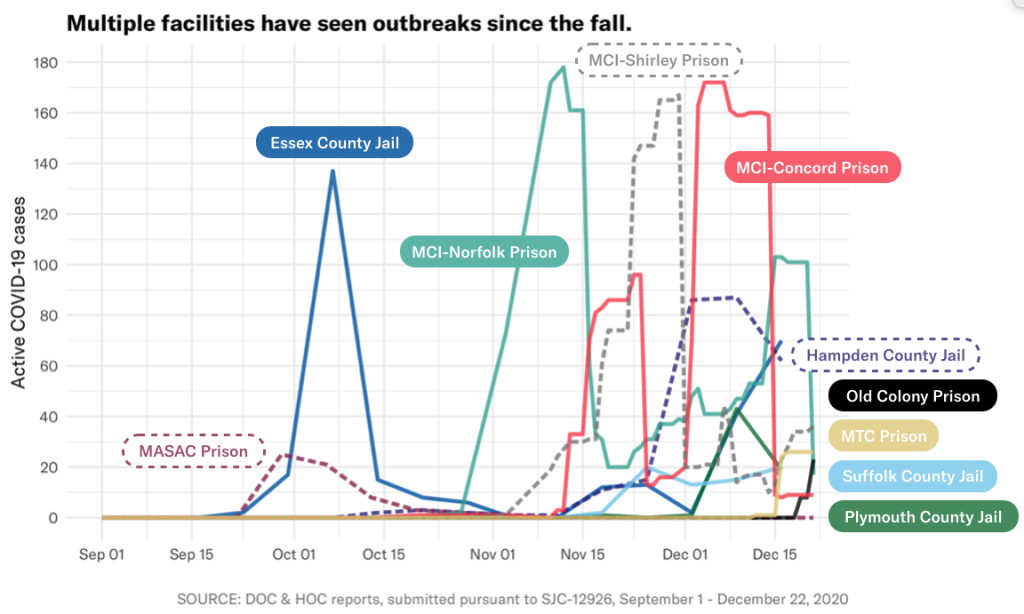

1. A battle against multiple simultaneous outbreaks

Since outbreaks of COVID-19 began increasing in Massachusetts in September, 27 prisons and jails statewide have seen more than 5 prisoners or staff infected with COVID-19. Seven facilities have seen more than 100 positive tests, and four facilities saw more than 100 simultaneous cases in a single outbreak.

In some state prisons, vast swaths of the facility’s prisoner population were (or are) infected at the peak of the outbreak, including: 33 percent of MCI-Concord (1 in 3) on December 7, 15 percent of MCI-Shirley on November 30, and 14 percent of MCI-Norfolk (1 in 6) on November 12.

| Facility Name | Positive tests (staff & prisoners), cumulative since Sept. 1 | Maximum active prisoner cases at peak of outbreak | Maximum active staff cases at peak of outbreak† |

| Barnstable County Correctional Facility | 10 | 0 | 9* |

| Bristol County Jail and House of Correction | 25 | 5 | 13* |

| Essex Middleton House of Correction | 257 | 137* | Not reported |

| Hampden County Correctional Center | 233 | 87 | 30* |

| Middlesex Jail & House of Correction | 46 | 9 | 26* |

| Plymouth County Correctional Facility | 123 | 43 | 35 |

| Suffolk South Bay House of Correction | 84 | 19 | 11 |

| Suffolk Nashua Street Jail | 41 | 17* | 8* |

| [DOC] Massachusetts Alcohol and Substance Abuse Center | 65 | 25 | Not reported |

| [DOC] MCI-Concord | 356 | 172 | Not reported |

| [DOC] MCI-Norfolk | 498 | 178 | Not reported |

| [DOC] MCI-Shirley | 337 | 167* | Not reported |

| [DOC] Massachusetts Treatment Center | 49 | 26* | Not reported |

| [DOC] North Central Correctional Institution | 228 | 83* | Not reported |

* - active positive cases stagnant or increasing as of December 22

† - no DOC facilities report active staff cases

The bottom line is that COVID-19 is raging across our jails and prisons, and the existing response is clearly proving inadequate.

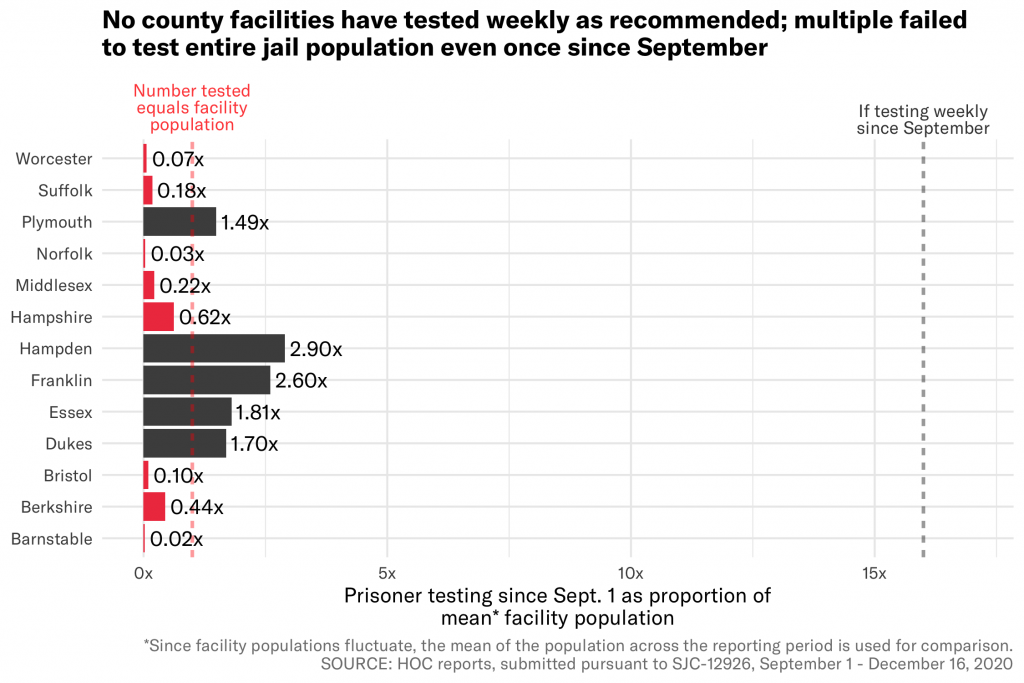

2. Testing has been consistently abysmal

There is a major and concerning caveat to available data on outbreaks: the numbers described above are just those COVID-19 cases that were confirmed via testing. Many prisons and jails are still not testing at a sufficient rate to detect and contain cases, and so there is reason to believe even the extreme outbreaks we’ve seen are underestimates.

Indeed, eight counties have not even conducted enough testing to account for their entire population once since outbreaks began accelerating in September. The most egregious examples include Barnstable County, which has conducted just 4 COVID tests since September while their prisoner population never dipped below 170and Worcester County, which has conducted just 39 COVID tests since September while their prisoner population never dipped below 566.

For comparison, Tufts University – which has a similar student population to the statewide prisoner population – has conducted almost as many tests in the previous 7 days (13,104) as all 13 county facilities have in the past nine months (13,562). And since August, Tufts has conducted more than 7 times as many tests (256,156) as all Massachusetts prisons and jails have since April (35,157).

And it’s not just private universities that are blowing jails out of the water; a state policy defined in June requires all staff at long-term care facilities to be tested weekly. The most recent state report showed that 407 of the 427 long-term care facilities in the state (95 percent) are currently compliant with this policy, as of the week of December 3-10.

The abysmal level of testing in jails is simply unacceptable, and they leave government officials effectively clueless as to whether new outbreaks are taking root across their facilities.

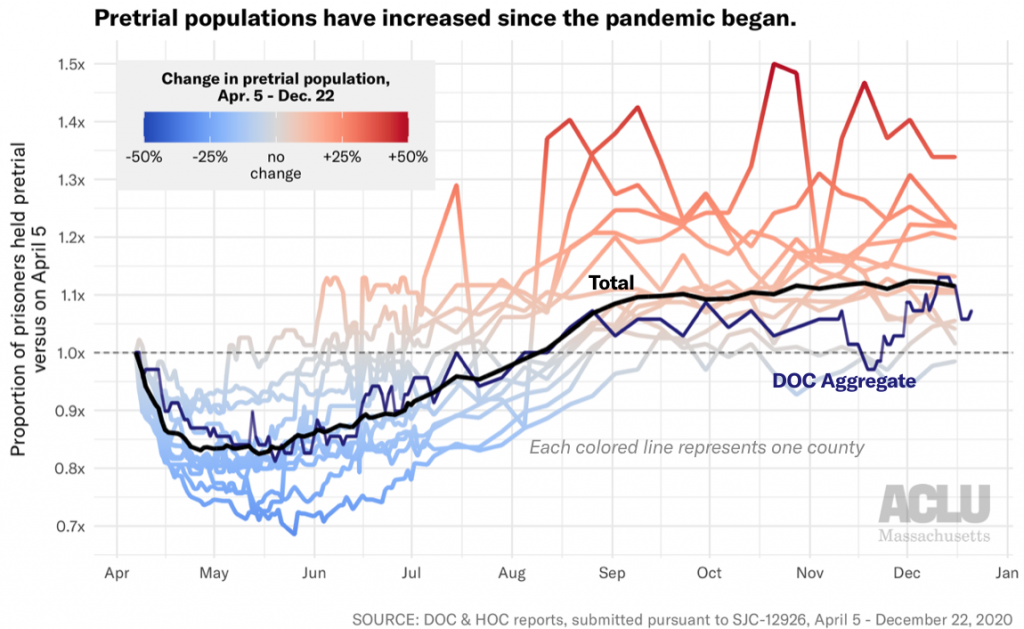

3. Rising prisoner populations increase danger

Yet testing is not the only preventative measure that prisons and jails have at their disposal, nor is it the only response that they are failing to properly implement.

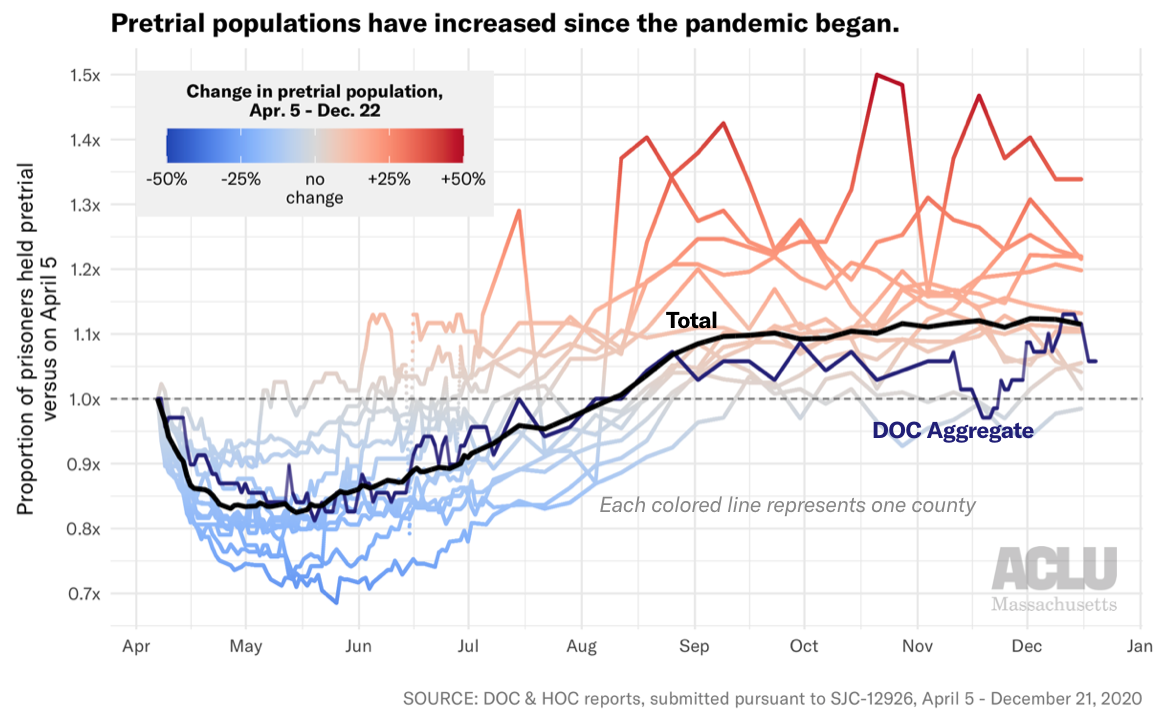

One of the most effective measures to curb the spread of COVID is to reduce the population of incarcerated people – fewer people in cramped quarters reduces spread and saves lives. But concerningly, recent data show that many facilities are actually increasing their populations now, after a drop in the spring. And the population of those being held pretrial – people who have not been sentenced with a crime but are currently incarcerated – is actually higher today than it was at the start of reporting in April. Over 400 more people are currently incarcerated pretrial than nine months ago: 4,355 on December 16 compared to 3,928 on April 5.

Franklin County saw the largest proportional increase with a 34 percent jump in pretrial prisoners since April – from 62 to 83. In larger facilities, the raw difference is even more stark: Hampden County has 106 more prisoners held pretrial today than in April (+22 percent), Bristol County has 86 more (+20 percent), Essex County has 84 more (+13 percent) and Suffolk County has 75 more (+11 percent). And across all DOC facilities, we also see a 7 percent increase in pretrial prisoners, from 69 to 74.

Overall, while the statewide incarcerated population fell by over 2,000 in the first few months of the pandemic, the population has risen by 300 since the lowest point in late June. Rather than further stuffing already crowded carceral facilities, Massachusetts should instead be following in the footsteps of states like Colorado, which has reduced their jail population by 46 percent during the pandemic.

One available tool for decarceration is to release those prisoners who are statutorily eligible to home confinement. Recent analysis by CPCS estimates that approximately 427 prisoners held in county facilities as of December 11, 2020 were eligible for home confinement programs. However, three of the 13 counties do not even have a home confinement program, and those that do have such programs not used them to meaningfully reduce their populations. Indeed, as of November 5, 2020, a total of just 16 individuals were on home confinement from a county facility. Similarly, while the DOC has a home confinement program, available data show it has made no placements since at least .

Prisons and jails need to use every tool in their toolbox to protect those in their care, and decarceration is one of the most effective tools. Massachusetts must drastically step up its prisoner releases and decarceration efforts immediately.

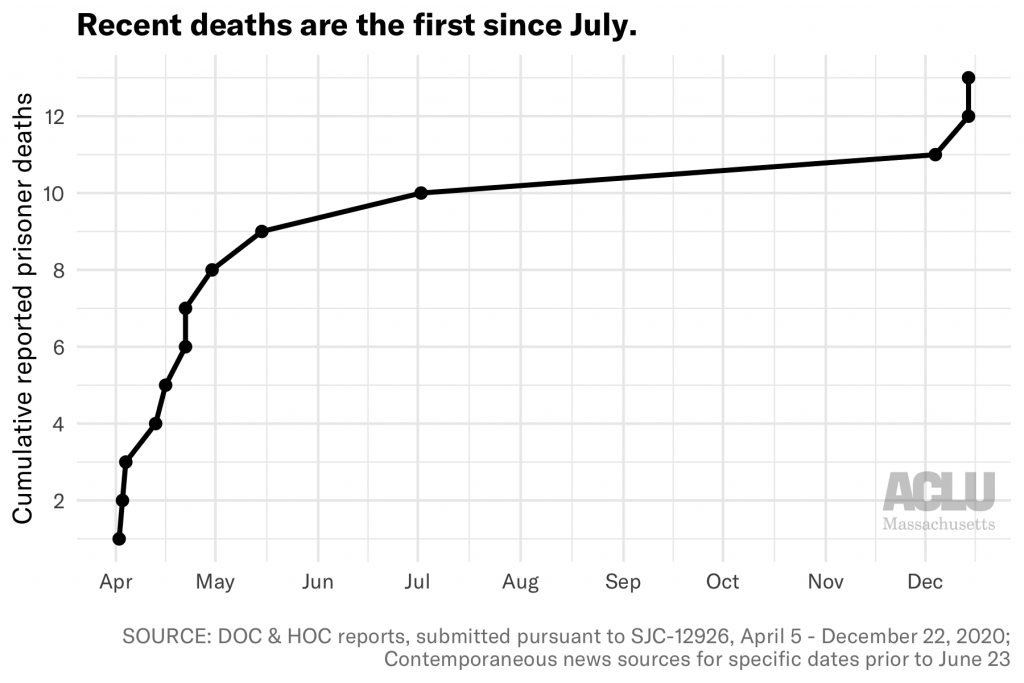

4. The consequences of inaction are fatal

Of course, these data on cases and positives represent human lives.

The DOC recently reported that a prisoner at MCI-Norfolk died from COVID-19 complications in their custody on December 4th. Two prisoner deaths were subsequently reported on December 14th, at MCI-Concord and MCI-Shirley. These reports come after the state saw no deaths for five months through the summer.

Furthermore, a shocking WBUR story in early December revealed that in at least two cases, the DOC approved medical parole for prisoners less than 24 hours before their death. Because these individuals were no longer technically in DOC custody, their deaths were not included in DOC reports to the petitioners.

One of these deaths was Milton Rice, a 76-year-old prisoner who had applied for medical parole in March, stating, "with my underlying health condition and compromised immune system issues, should I contract the COVID-19 virus it would more than likely be fatal for me." He was finally granted medical parole on November 24, two weeks after testing positive, and he died of COVID-19 pneumonia on November 25 – the day before Thanksgiving.

As counsel in the SJC case wrote on March 24th, "There are about 16,500 human beings in our prisons and jails. None of them have been sentenced to death. Yet, without aggressive and immediate intervention, COVID-19 will likely kill many of them." We have seen at least 13 deaths since then, with no appropriate response in sight.

The numbers presented here describe only the tip of an iceberg of an inadequate COVID-19 response. In a federal filing last month, Plymouth County Correctional Facility stated that asymptomatic staff at their facility were “not required to quarantine following an exposure to COVID-19.” One such staff member who returned to work tested positive less than a week later. Plymouth has since indicated that it has “resumed quarantining all close contacts and will only reduce the quarantine period in the future as required to maintain the safety and security of inmates and detainees.” Lockdowns, restrictions on visitation, and the use of solitary confinement as quarantine have been widely implemented – to the detriment of prisoners’ mental health over the past nine months. And throughout the pandemic, there have been reports from inside facilities of staff not consistently wearing masks or PPE.

Two weeks ago, Governor Baker’s office announced that Massachusetts will become one of the few states to include incarcerated individuals in Phase One of the statewide COVID vaccination plan. While this is an important and necessary measure for the future, it does not absolve the government of its responsibility to protect prisoners today; major changes are necessary to ensure that prisoners stay alive long enough to receive a vaccine. And for many, the vaccine will be too little and too late to right the wrongs affected by harmful policies over the past nine months. We know of at least 2,500 Massachusetts prisoners who have already been infected with this disease, and the consequences for their families and communities will be long-lasting.

Also two weeks ago, Governor Baker vetoed line item 8900-0001 from the proposed FY21 budget, which would create an independent ombudsman office to monitor COVID-19 in prisons:

https://twitter.com/justicehealing/status/1337499657069621250

The proposed office was a hard-fought victory by advocacy groups such as Families for Justice as Healing (FJAH), and already represented a legislative compromise. Unfortunately, this veto is just further evidence of the state’s failure to take sufficient action to protect those in their custody in the midst of this pandemic.

State and county governments in Massachusetts must take responsibility for the humanitarian crisis currently threatening – and killing – those in their care. They must drastically increase testing and both pretrial and post-conviction releases immediately, and provide more transparency on how vaccines will be distributed inside prisons and jails.

Take action:

- Use the Building Up People Not Prisons Coalition’s toolkit to contact your state legislators and urge them to override Baker’s veto of the correctional oversight office

- Use FJAH’s toolkit to contact the Department of Public Health commissioner and Department of Correction commissioner, urging them to reduce prison and jail populations and systematize COVID-19 testing

Bond Bill Funds Prisons and Police over Education

Editor's Note: Today, the Senate Bonding Committee gave S2579: the General Government Bond Bill (previously H.4733) a favorable report. Last week, the committee on Senate Bonding, Capital Expenditures and State Assets concluded hearings on this bill. We are glad to see that the committee added limiting language to ensure that the $150 million authorization for public safety facilities would not be spent on building new prisons or jails. As the bill advances to Senate Ways and Means, we hope to see more amendments that prioritize investment in communities rather than policing and prisons.

What is the “General Government Bond Bill” and why should we care?

Last week the committee on Senate Bonding, Capital Expenditures and State Assets concluded hearings on H.4733, the General Government Bond Bill (originally H.4708). This Bond Bill intends to finance general governmental infrastructure of the Commonwealth around “public safety, information technology and data and cyber-security improvements.”

Bond bills are borrowing bills which pass on not just debt to future generations but also values. Given the huge disparities the pandemic has both exposed and created through mandatory remote learning, the top priority for any debt for future taxpayers should in fact be their current education. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown how crucial basic broadband infrastructure is to ensure equitable access to education. Education Commissioner Jeff Riley testified last month to the need of $50 million to support MA school districts to reach students without internet access (9% of students) or exclusive use of a device (15% of students).

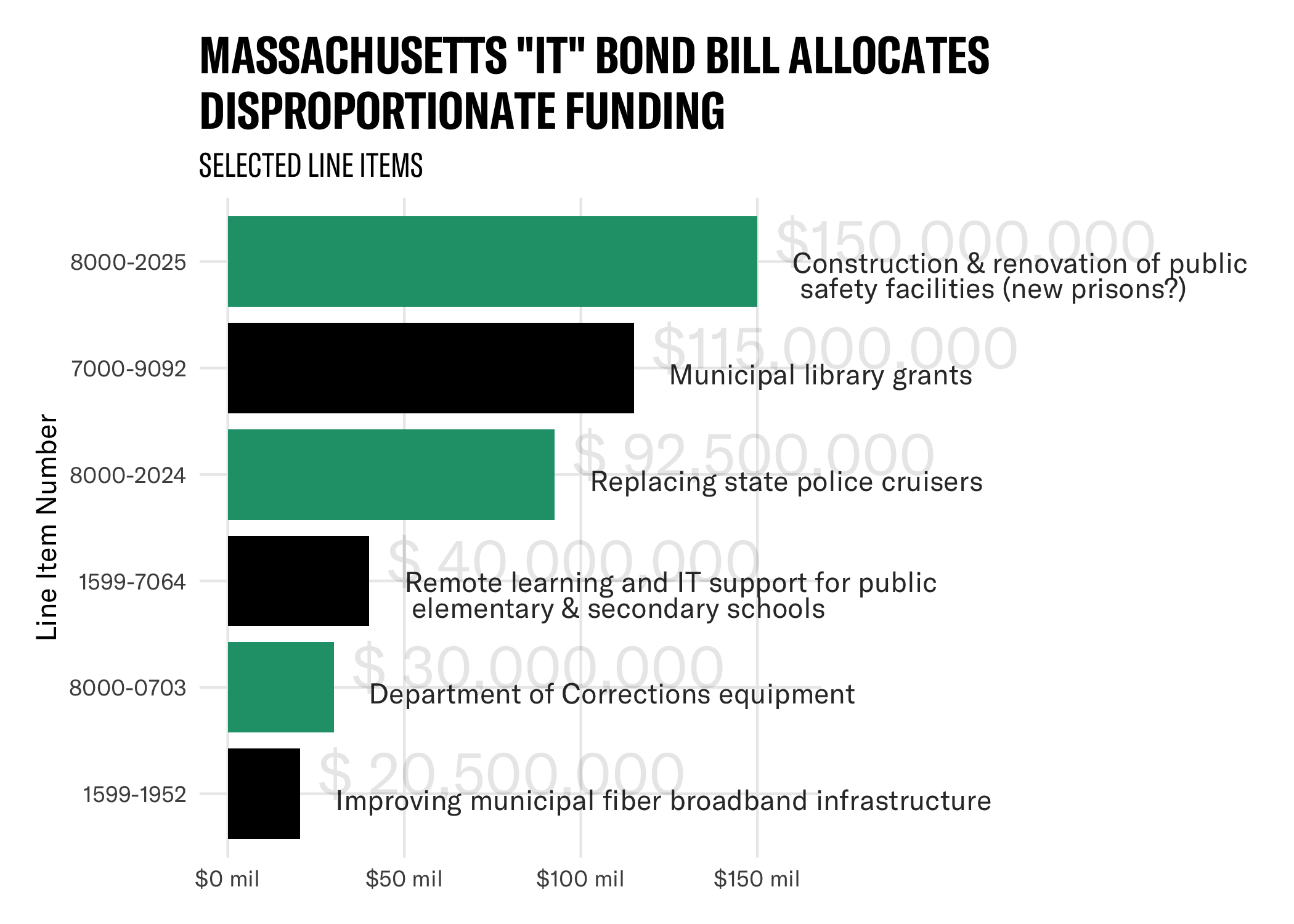

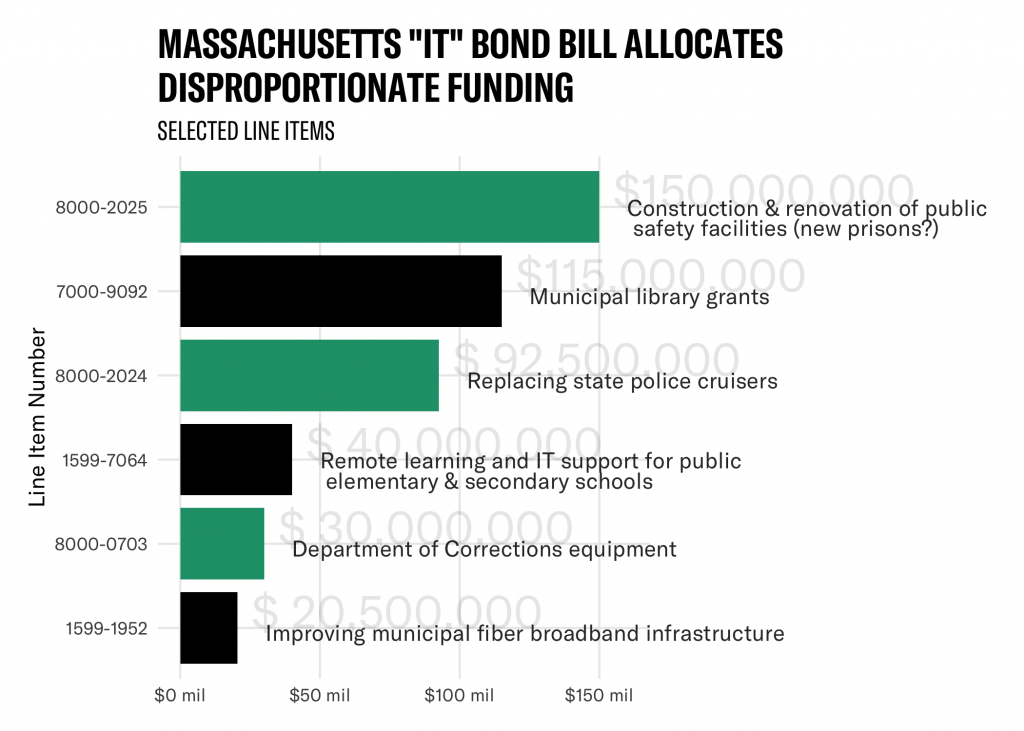

Instead, this bill allows for at least $270 million to build prisons, acquire police cruisers and other equipment for the Department of Corrections. The events of the last few weeks have shown the unnecessary, unwise, and unjust investment in the criminal legal system -- a system that over-polices, over-prosecutes, and over-incarcerates Black and Brown communities in the Commonwealth. The bill’s funding priorities need to be flipped.

As the Boston advocacy organization Families for Justice as Healing states in their call to action against H.4733, "The Commonwealth already spends more money per capita on law enforcement and incarceration than almost any other state. Communities need capital money for critical infrastructure projects like housing, carte facilities, parks, schools, treatment centers, healing centers, community centers, and spaces for art, sports, and culture."

Why are we still investing in police and prisons?

Over the last week, the world has watched as protests against police brutality and unaccountability have been met with further use of excessive force on protestors. As we live through the historic Black Lives Matter movement, the ACLU of Massachusetts (ACLUM) has joined the calls of Black and Brown-led organizations to divest from police in favor of investments in systems that support, feed, and protect people.

There have been demands from across the country to defund police departments, with the Minnesota City Council declaring its intent to disband the police department all together. The timing of further funding of police departments is incomprehensible at this watershed moment for racial justice across the country and in the midst of an economic freefall due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bond bill H.4733 does not meet this moment. In testimony to the Senate Committee on the Bond Bill, ACLUM strongly opposed line item 8000-2025, which would authorize an enormous amount of borrowing to build prisons. Families for Justice as Healing also opposed this line item, testifying that "significant decarceration is possible and further decarceration is doable and practical under current law, and at a cost-savings to the commonwealth."

ACLUM also opposed line item 8000-0703, authorizing the borrowing of $30 million for the purchase of Department of Corrections and Executive Office of Public Safety and Security for equipment and vehicles, and line item 8000-2024, authorizing the borrowing of $92 million for the purchase of police cruisers. (This is enough to put over $40,000 towards a new or improved car for all 2,199 Massachusetts State Police employees.)

Even without bond funds, police departments across the Commonwealth and the country are incredibly well funded. As previous ACLUM analysis of the City of Boston budget on Data for Justice shows, compared to the budgets of other Boston City departments (and cabinets), the Boston Police budget is exponentially higher than that of community focused organizations like Library, Neighborhood Development and Office of Arts and Culture.

Why aren’t we investing in actual information technology infrastructure?

Instead of authorizing new debt to build prisons and increase police budgets, we should be investing in information technology to support educational equity throughout the Commonwealth. In that way, this bond bill could truly reflect values we want to pass down to our children.

At present, the line item 1599-7064 is the only one which directly does this, authorizing $40 million to help close the digital divide for students in the Commonwealth. Certain emergency measures have been taken by school districts to enable transition to remote learning such as tablets and free access to assistive technology. However a bill that is intended to finance the general governmental infrastructure of the Commonwealth, and in particular to provide assistance to public school districts for remote learning environments, should invest in more than $40 million in state-wide digital infrastructure to permanently close the digital divide.

What exactly do we need to invest in?

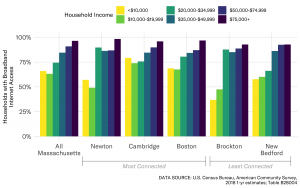

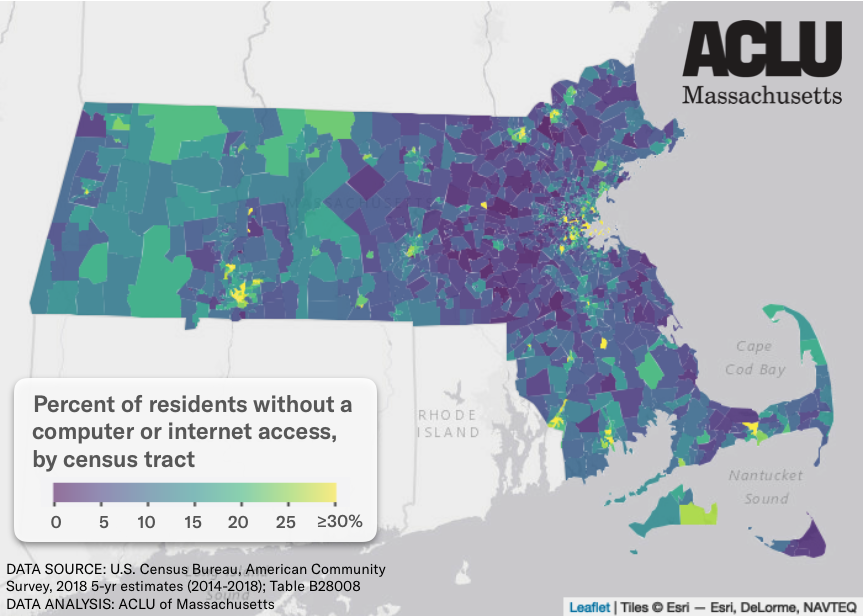

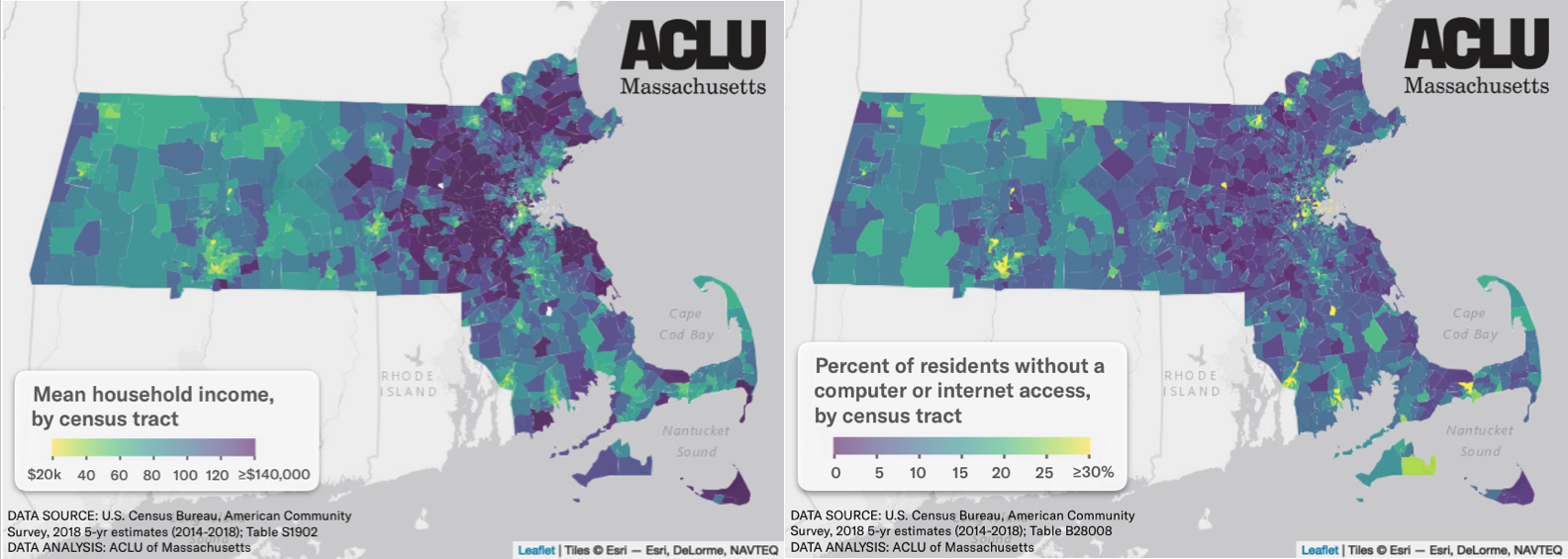

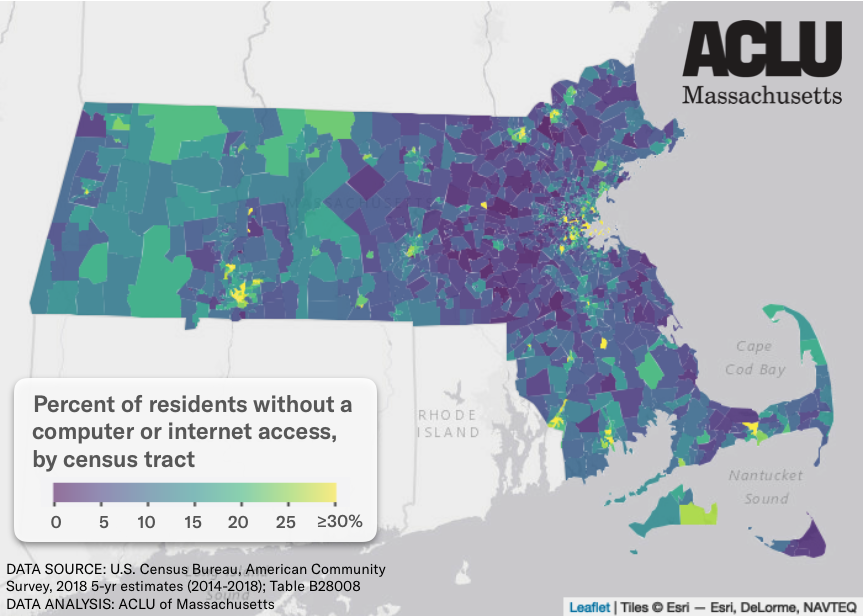

Data from the United States Census American Community Survey show that about 8% of households either do not have a computer, or if they do, do not have access to the internet at all. Furthermore, more than 1 million Massachusetts residents (> 15%) do not have a fixed broadband internet connection.

As reported in a previous analysis by the ACLU of Massachusetts, lower rates of internet access or broadband correlate with lower income, both in terms of macroscopic geography (e.g. southern and western Massachusetts), and low-income neighborhoods within cities. 8 cities in Massachusetts have at least 30% of households without cable, DSL or fiber Internet subscriptions in 2018 - Fall River, Springfield, Lowell, Lawrence, Worcester, Lynn, New Bedford and Brockton.

Taking a closer look at Brockton for example: of the households in the lowest two income categories, less than 50 percent have broadband internet access. This is similar to the pattern of better connected cities such as Newton. Here too, about 50 percent of households in the lowest two income categories do not have broadband. Thus from the perspective of a household, one's income is a stronger indicator of access to the internet, even if one is living in an area which generally has robust high speed internet connectivity.

Divest - Reinvest

Bond bill H.4733 singles out certain cities for specific projects. Brockton, for example, is slated to get $2,000,000 for enhanced security camera systems at public housing buildings Campello and Sullivan towers. Instead of investment in broadband, Lawrence, which ranks 28th on the list of 623 worst connected cities in the country, is going to get $2,500,000 for police cruiser technology.Thankfully Springfield, ranked 24 on that list, is slated to get $7,500,000 for a citywide fiber network.

Beyond Education Commissioner Jeff Riley’s testimony on the need of $50 million for remote elementary and secondary education, State and community colleges are in dire need of funding as well. The community colleges’ chief financial officers recently tallied the costs of additional information technology at nearly $17 million.

Rather than expanding the racist carceral state, we should use this Bond Bill to create equitable digital infrastructure to even out the playing field for the future generation.

Internet Deserts Prevent Remote Learning During COVID-19

Across the country, closures due to COVID-19 are forcing families and schools to take extreme measures just to get students to class, because they lack one essential resource: internet access.

From Michigan to Alabama, Pennsylvania to Oregon, school buses are being transformed into roving wi-fi hotspots. Some rural students have no choice but to drive miles to sit in parking lots of fast food restaurants and churches in order to access the internet. In Fort Worth, Texas, a school district bought three transmission towers for $600,000.

Here in Massachusetts, school districts reports show that while wealthy regions like Andover report online student participation around 95 percent, lower income areas like Chelsea are seeing attendance as low as 30 percent.

Many school districts such as Springfield and Chicopee have distributed technology, like laptops and tablets, to students. However, a laptop without internet is just as useful for modern schoolwork as a car without gas is for driving. Without the final piece of the puzzle, it’s just a glorified hunk of metal.

Using data from the Census’ American Community Survey, the ACLU of Massachusetts presents analysis of internet and computer access across the Commonwealth. We show that many urban and rural areas in Massachusetts are “internet deserts”, where access is severely limited.

Learn More: Visit our interactive site which allows detailed exploration of internet access and related social factors across Massachusetts.

Hotspots without computer or internet access

According to estimates from 2014-2018 census data, over 500,000 Massachusetts residents either do not have a computer or, while having a computer, do not have access to the internet. Statewide, this represents 8 percent of all Massachusetts residents. However, in certain regions in the Commonwealth – so-called internet deserts – over 25 percent of residents, 1 in 4, do not have a computer or internet access.

Massachusetts’ urban areas, including Boston, Lowell, Lawrence, Worcester, Springfield, and Northampton, all have neighborhoods in which over 30 percent of residents live without wi-fi. But rural areas are affected as well: northwestern and southwestern Massachusetts also have large regions where almost 20 percent (1 in 5) of folks don’t have access.

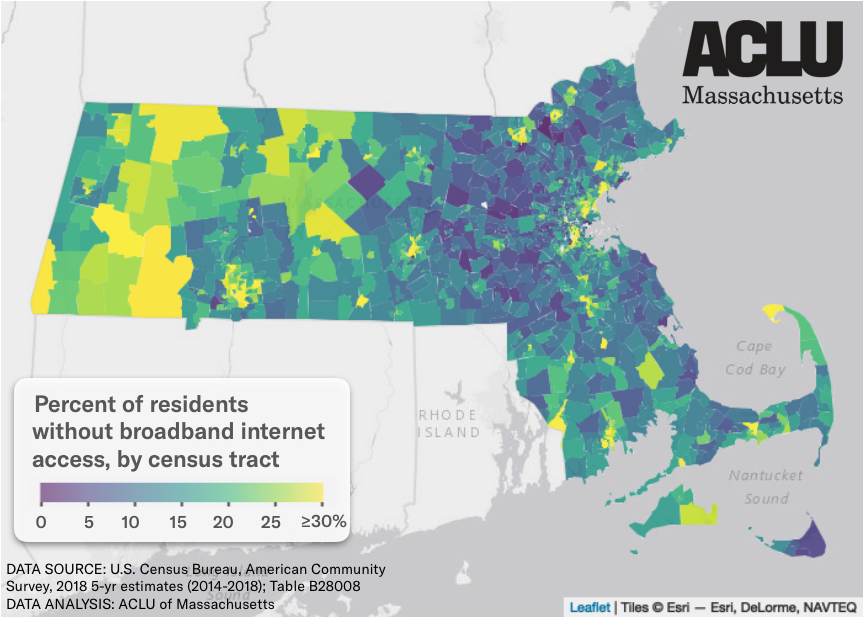

Even more without broadband internet

However, not all internet is created equal. High-speed broadband internet connections, rather than slower dial-up, are necessary for effective use of video conferencing software. Without broadband, remote students may have extra technical difficulties which prevent their participation in school.

Census estimates show that more than 1 million Massachusetts residents, over 15 percent, do not have a fixed broadband internet connection.

Again, localized areas see much higher rates: all major Massachusetts cities and large swaths of rural Western Massachusetts contain regions where over 30 percent of residents have no reliable broadband wi-fi.

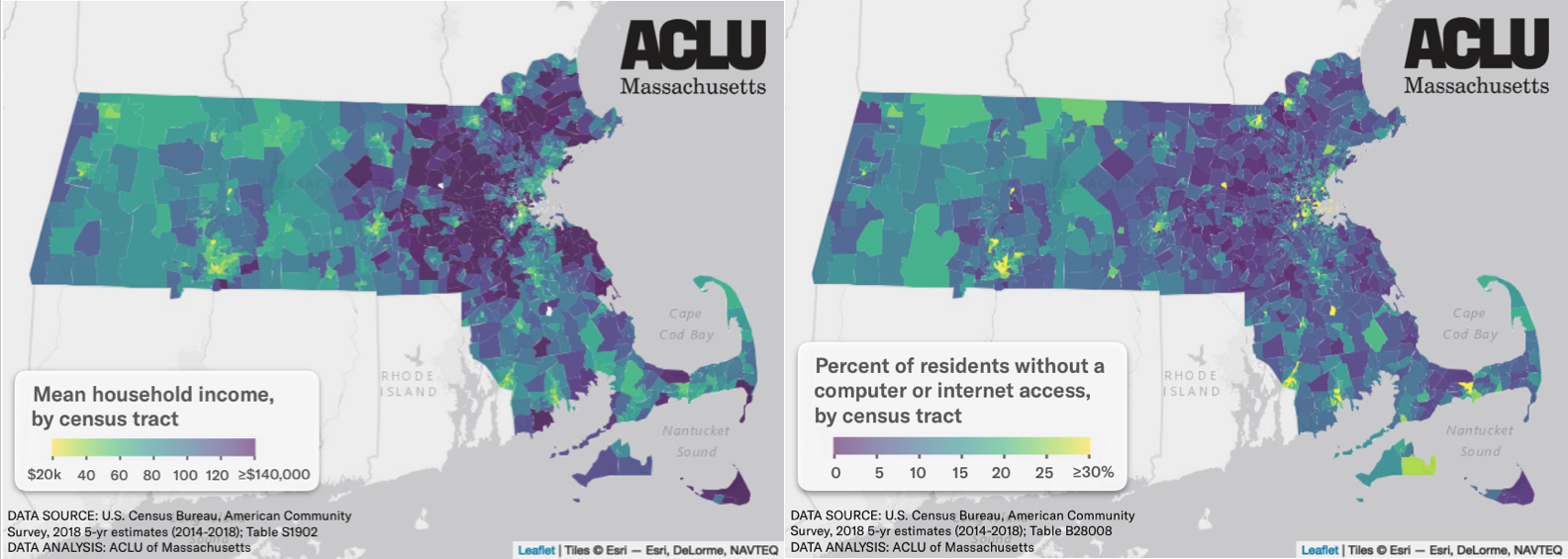

Low-income areas are the most disconnected

Of course, unequal access arises from the fact that internet subscriptions cost money. Census analysis shows that internet and computer access correlate with income, such that areas with higher income communities enjoy more widespread access, while lower income neighborhoods are disproportionately left unconnected.

In the extreme era of COVID-19, it’s important to note that this analysis uses income estimates from up to only 2018. The global economic downturn and widespread job losses caused by the pandemic mean that many households are now earning much less than they did in 2018, and thus presumably even more households are going without wi-fi.

Tens of thousands of students offline

Further analysis breaking down estimates of internet access by age reveals that over 60,000 people under the age of 18 in Massachusetts, around 4 percent of all minors, have no computer or internet access at home.

Indeed, in multiple school districts across the state more than 20 percent of minors have no access to wi-fi, including those already shown to be located within internet deserts: Springfield, Lowell, Lawrence, and Petersham School Districts (Worcester).

What about your town?

Use this interactive map to explore internet access and income across Massachusetts:

As the ACLU of Massachusetts emphasized in a recent letter to the Commonwealth’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE): unequal education isn’t just unacceptable; it’s unlawful.

DESE must take action to increase resources in low income school districts. Some individual districts, including Amherst, Chicopee, and Holyoke have set examples by providing mobile hotspots to families and securing deals with internet providers to get students free access. Now the state, too, must step up to ensure all students have access to not only computers and tablets but all of the following as well:

- Functional microphones and webcams

- Broadband internet supportive of remote video meetings

- Hardware and infrastructure required for an internet connection (e.g. cable line, modem, & router)

- Communications platforms free of charge

- Assistive technology including but not limited to screen readers, live closed captioning, and speech-to-text software for students with disabilities

- Software and websites compliant with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)

- Privacy assurances for all software and devices

- Instructions written in plain English and appropriate non-English languages, such that students’ families understand and can support remote learning efforts

The Massachusetts Constitution requires that the Commonwealth provide adequate education to all students. And while remote learning is certainly a necessary measure in promoting public health, the current state of affairs means far too many Massachusetts students are now home without even the basic infrastructure for academic participation.

Incarcerated and in Danger: COVID-19 in Massachusetts Prisons & Jails

While the COVID-19 pandemic poses a massive threat to the general population, imprisoned populations face even higher risks due to close living quarters, poor hygiene, and inadequate medical attention.

On April 3, 2020, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts (SJC) in Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS) v. Chief Justice of the Trial Court, SJC-12926 issued an order that will help some incarcerated people in Massachusetts seeking release in response to the threat of COVID-19. Per its decision, the Court now allows some people detained pre-trial to request a hearing for their release where they will be entitled to a rebuttable presumption of release. The Court also ordered daily reports from prisons, jails, and houses of corrections across the state.

Each day, these reports document how many COVID-19 tests are performed on prisoners and staff, how many tests return positive, and how many people are released from confinement pursuant to the Court’s decision. Analysts and developers at the ACLU of Massachusetts have developed a new interactive tracking portal to make these data available to the public and perform preliminary analysis of trends.*

Here we present four major takeaways from the first week of reports, illustrating that Massachusetts prisoners already face an exceptional threat due to COVID-19.

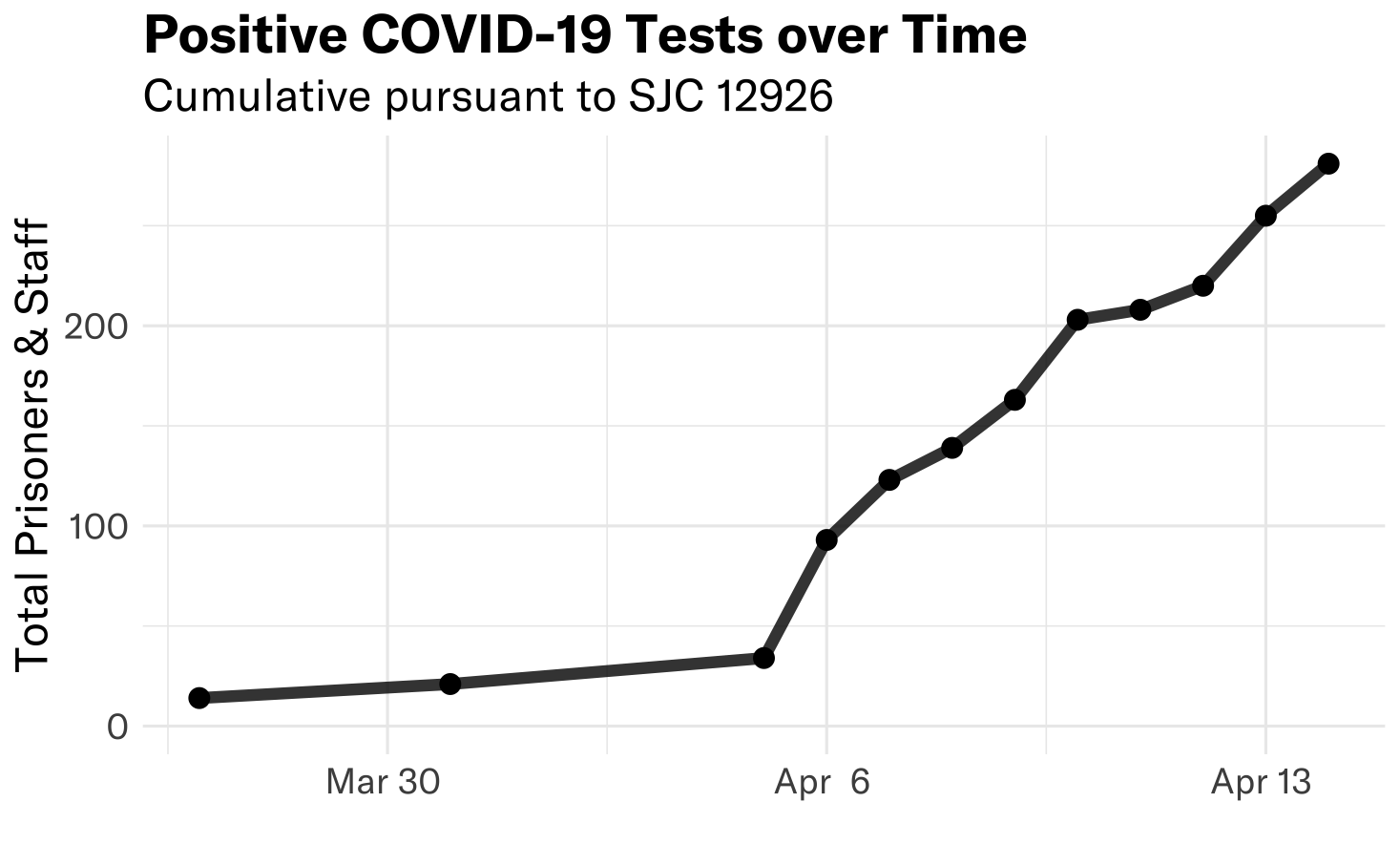

1. COVID-19 cases are skyrocketing in prisons and jails

Statewide, the number of positive COVID-19 cases inside prisons and jails is increasing at a terrifying rate. In just one week, the total number of reported positive cases increased over 200 percent, from 93 prisoners and prison staff who had tested positive by April 6 to 281 positive tests by April 14.

State Department of Correction (DOC) facilities alone account for 62 percent of all cases, reporting 158 positive cases by April 14.

Certain individual facilities have become frightening hotspots, too, with positive cases in Essex County increasing 375 percent from 9 cases on April 6 to 43 cases on April 14. And at the Massachusetts Correctional Institution in Framingham, over 10 percent of prisoners have tested positive for COVID-19.

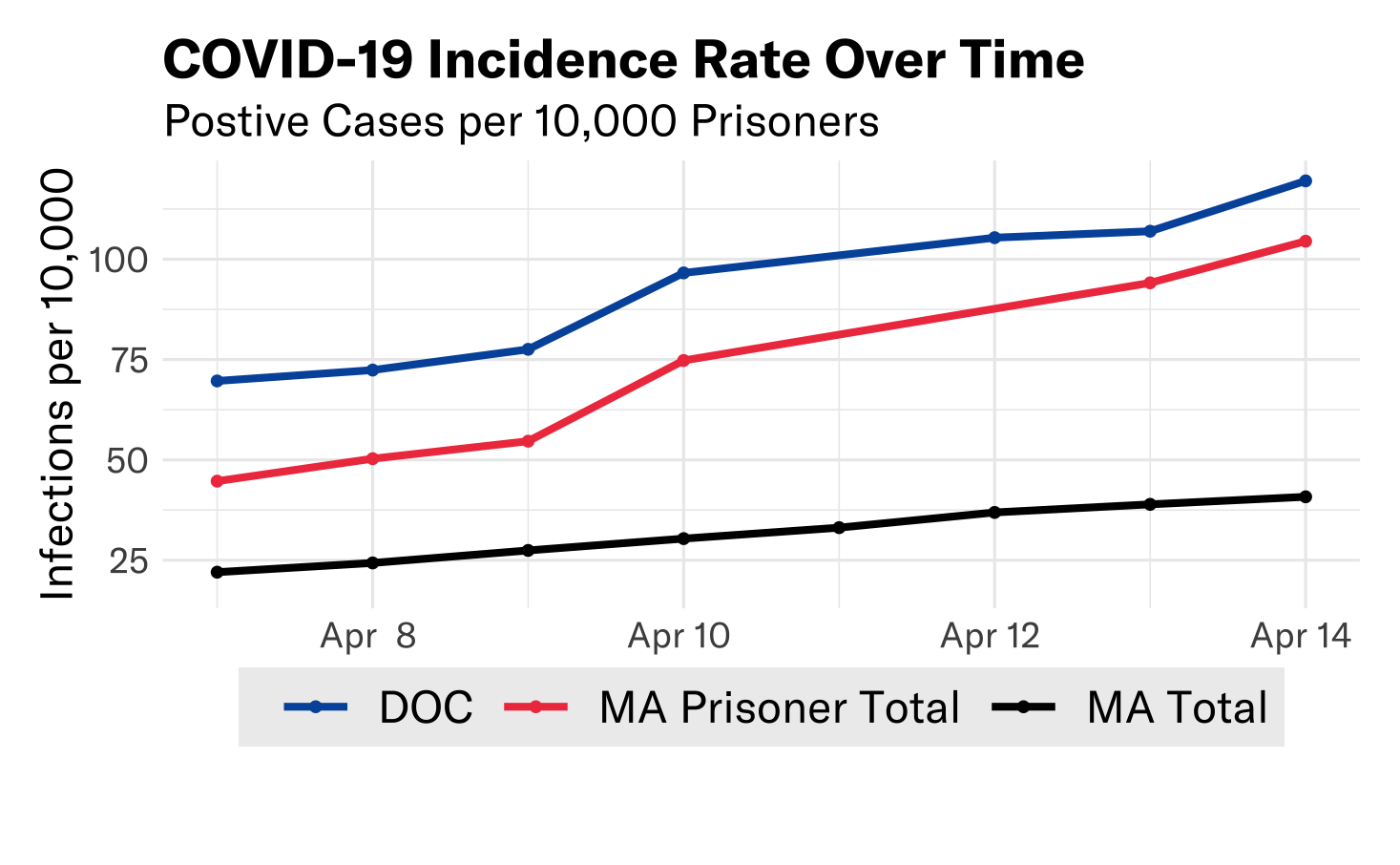

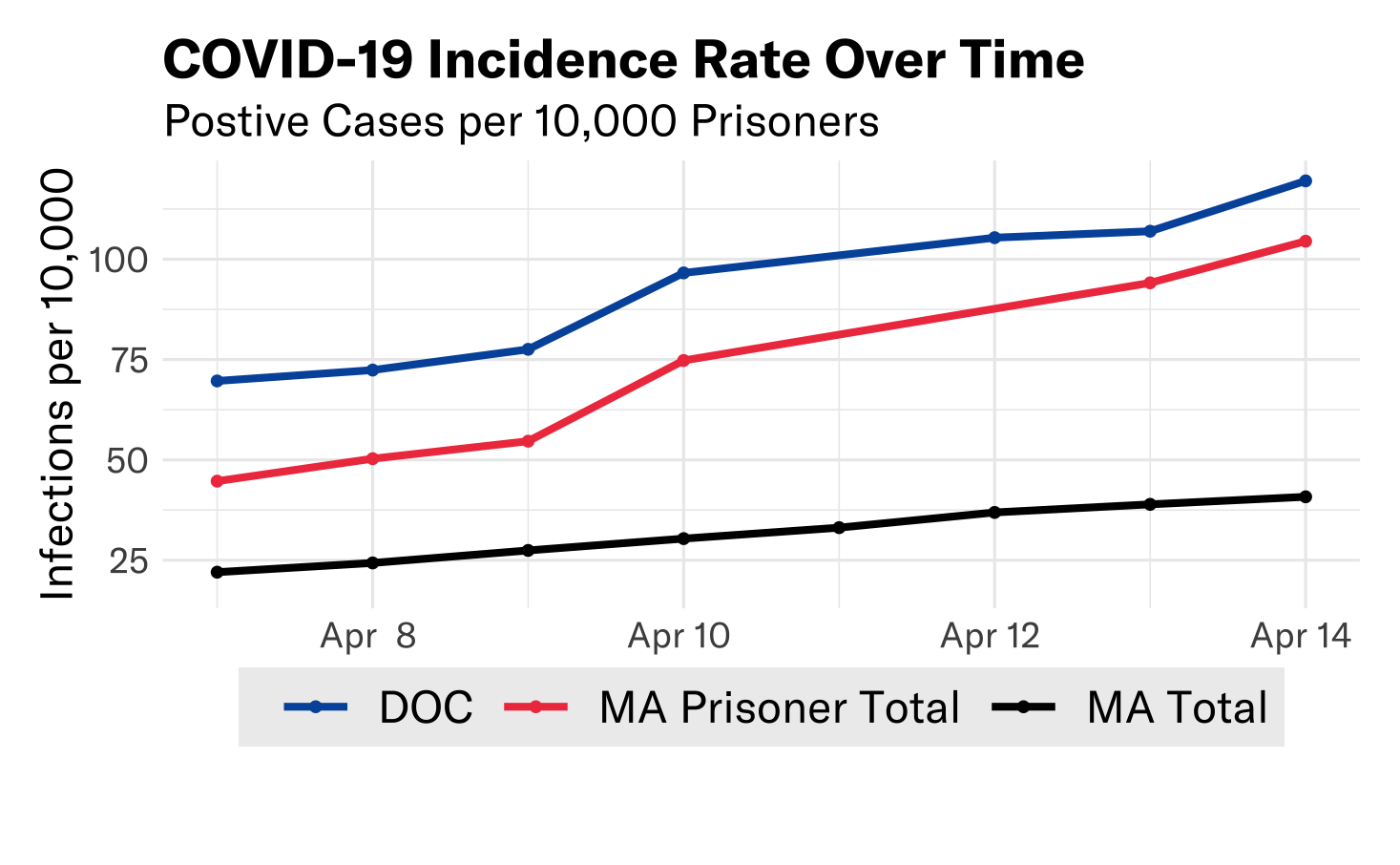

2. Rates of COVID-19 inside prisons and jails are much worse than statewide

As of April 14, the COVID-19 incidence rate among all prisoners incarcerated in Massachusetts is 104 reported positive cases per 10,000 prisoners. In DOC facilities, the situation is even more dire, with a case incidence rate of 120 reported positive cases per 10,000 prisoners.

For comparison, on April 14 Massachusetts reported a statewide case incidence rate of 41 reported positive cases per 10,000 residents. This means the incidence rate of COVID-19 among prisoners within correctional facilities is over two times higher than the statewide rate.

Yet looking to criminal justice facilities nationwide, it is clear that things can get much, much worse. According to the Legal Aid Society, the COVID-19 incidence rate at Riker’s Island Prison in New York City was 814 reported positive cases per 10,000 people on April 14.

Yet looking to criminal justice facilities nationwide, it is clear that things can get much, much worse. According to the Legal Aid Society, the COVID-19 incidence rate at Riker’s Island Prison in New York City was 814 reported positive cases per 10,000 people on April 14.

The meteoric increase of cases in Massachusetts facilities suggest we might reach similarly astronomical numbers soon – unless courts and criminal legal system officials take immediate action.

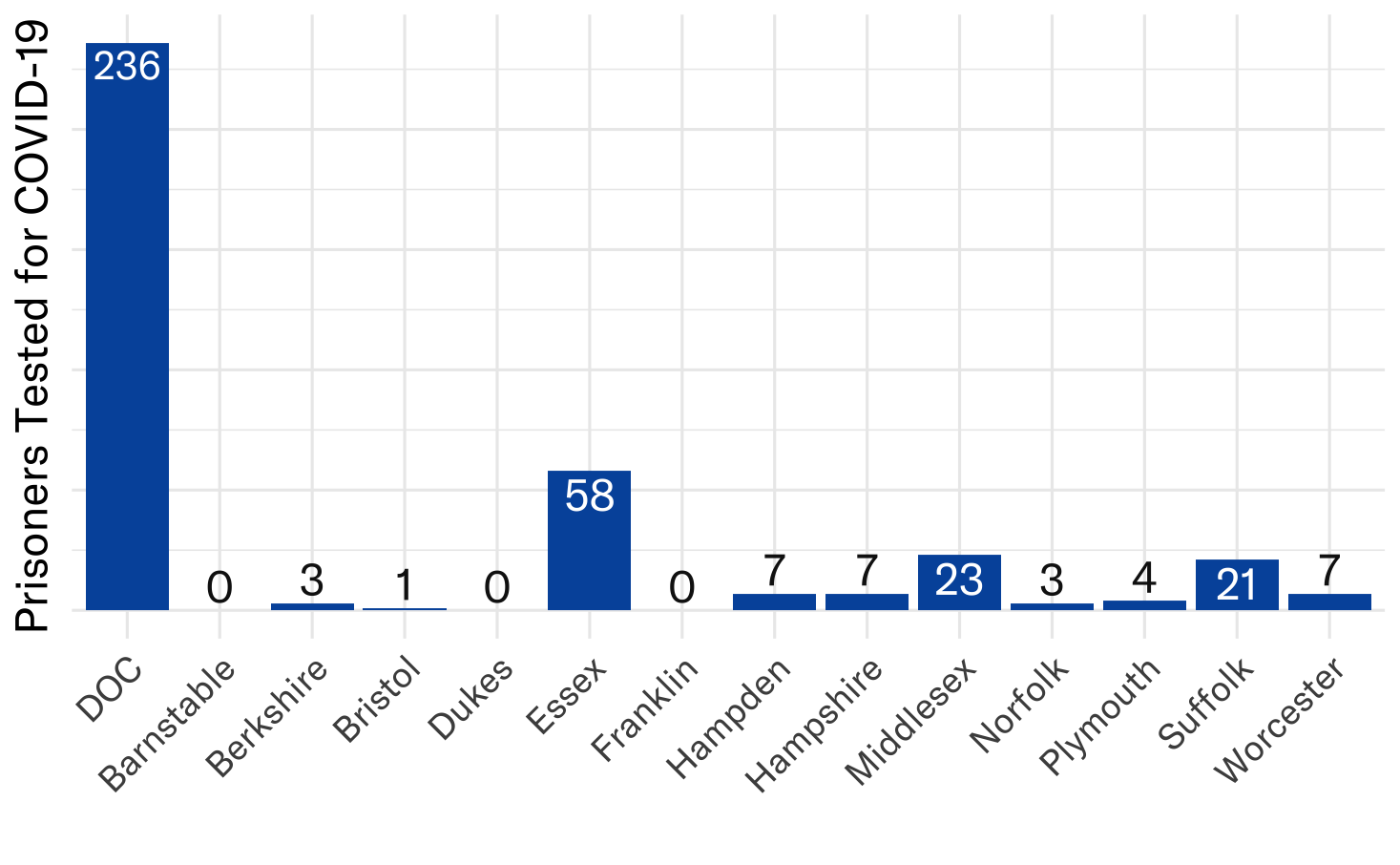

3. Testing in some MA prisons and jails is abysmal

Access to COVID-19 tests in the United States is insufficient nationwide, and the situation is even worse within Massachusetts county jails.

Multiple county sheriffs have not reported testing a single prisoner for COVID-19 since at least April 5. Such counties include Barnstable and Franklin Counties, whose correctional facilities together incarcerate over 300 people.

Other counties have reported testing at unacceptably low rates: Bristol County has administered a COVID-19 test to just 1 of its over 600 prisoners (0.2%); Norfolk County has tested just 3 of 368 (0.8%); Plymouth County, 4 of 744 (0.5%).

Compare this to testing rates across Massachusetts, where 126,551 tests have been administered as of April 14, for a statewide testing rate of 1.8 percent.

Tests of jail employees, including correctional officers, contractors, and other staff, are lacking as well. Bristol County and Suffolk County have not reported administering a single COVID-19 test to any of its staff, again since at least April 5.

Altogether, the positive rate of tests performed on all prisoners and staff is 49 percent (281 positives from 578 tests). This massively inflated rate reflects not only that COVID-19 is running rampant within prisons and jails, but also that nowhere near enough tests are being performed to inform proactive decisions; these facilities are playing whack-a-mole with prisoners’ and correctional officers’ lives.

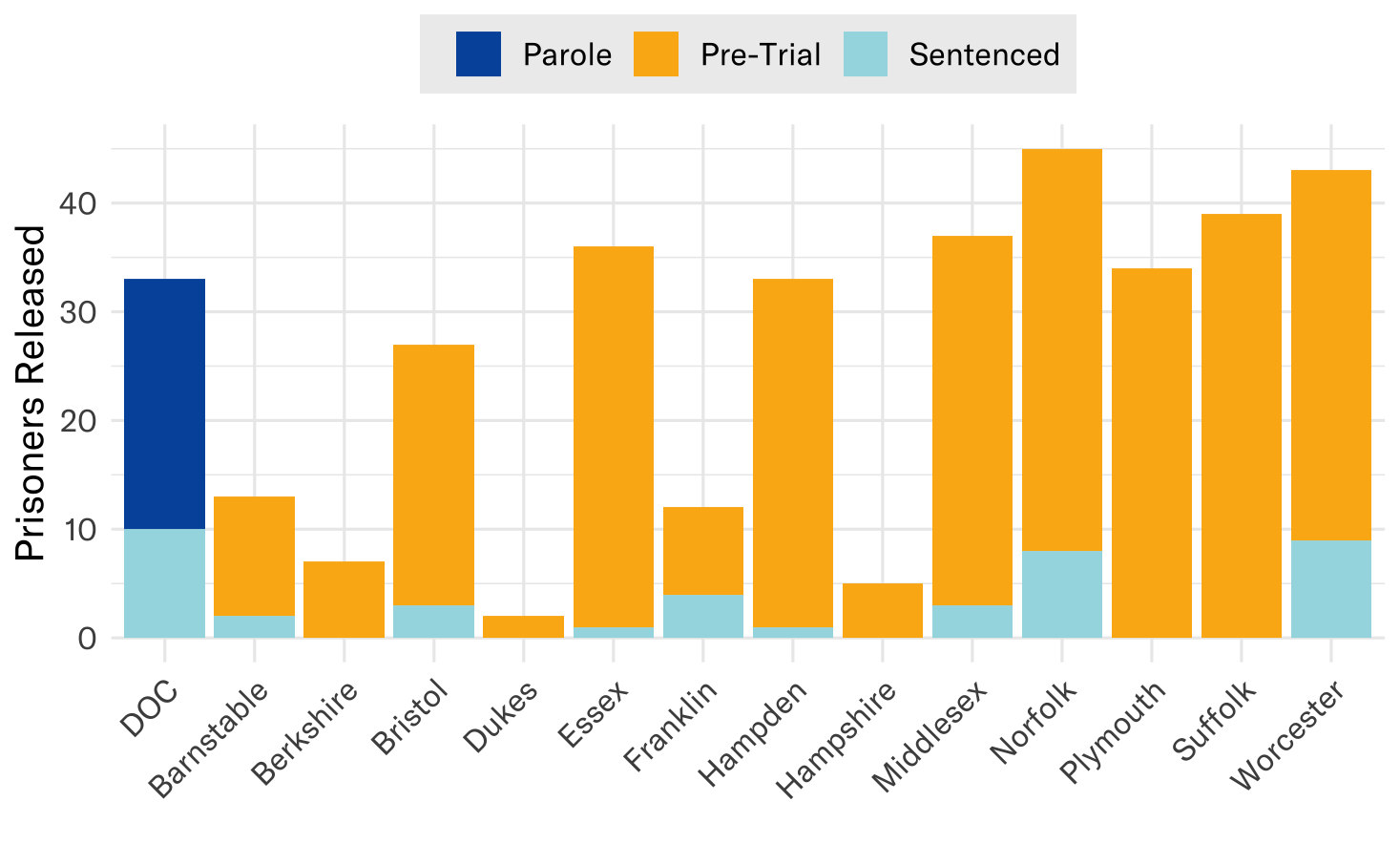

4. SJC decision leads to some prisoners released – but not nearly enough

Some good news is that the Supreme Judicial Court decision has indeed led to the release of some people from incarceration. As reported to the Court, 366 prisoners have been released pursuant to the ruling in SJC 12926. Of these, over 80 percent are releases of pre-trial detainees who have not been convicted.

This result is significant for these 366 people and their loved ones. But releasing such a small number of people will not stop the crisis from overtaking our prisons and jails—putting incarcerated people, prison and jail staff, and the entire community at greater risk of infection and death.

This is why, in an open letter to public officials on March 18, the ACLU of Massachusetts urged Governor Baker to grant emergency commutations for “people whose sentence would end in the next year, to anyone currently being held on a technical supervision violation, and to anyone identified by the CDC as particularly vulnerable whose sentence would end in the next two years.” Neither the Supreme Judicial Court nor the governor have acted yet in favor of release for such sentenced prisoners, and only 41 sentenced prisoners have been released.

Governor Baker can and must protect these vulnerable individuals, or they will remain trapped inside increasingly dangerous facilities with no available options for recourse, and many will die.

The best available data on COVID-19 in Massachusetts prisons and jails suggest that many facilities are death traps where inmates and staff alike suffer from skyrocketing rates of infection and insufficient testing.

In a new letter submitted on April 14, the ACLU of Massachusetts and the Massachusetts Public Health Association once again urged the Governor to take action to release incarcerated individuals in the face of pandemic, by (1) ordering the Parole Board to expedite previously-made parole decisions for hundreds of people who have been granted parole but have not yet been released; (2) amending the Executive Clemency Guidelines in light of the pandemic and (3) directing the Advisory Board of Pardons to expedite the processing of pending clemency petitions.

As the Petitioners in CPCS v. Chief Justice of the Trial Court explained in their emergency petition to the Court on March 24, "There are about 16,500 human beings in our prisons and jails. None of them have been sentenced to death. Yet, without aggressive and immediate intervention, COVID-19 will likely kill many of them."

Four prisoners have died of COVID-19 in Massachusetts since that emergency petition was filed. We don’t need to wait for that number to climb higher before declaring a crisis within our prisons and jails. Unfortunately, the data show that crisis is already here. The time to act is now.

*The Special Master in CPCS v. Chief Justice of the Trial Court released a report on April 14th publishing data that conflict with data reported here and in our web tracker. The ACLU of Massachusetts is aware of the disparities, understands their causes, and is in the process of communicating with the Special Master to resolve the issue.

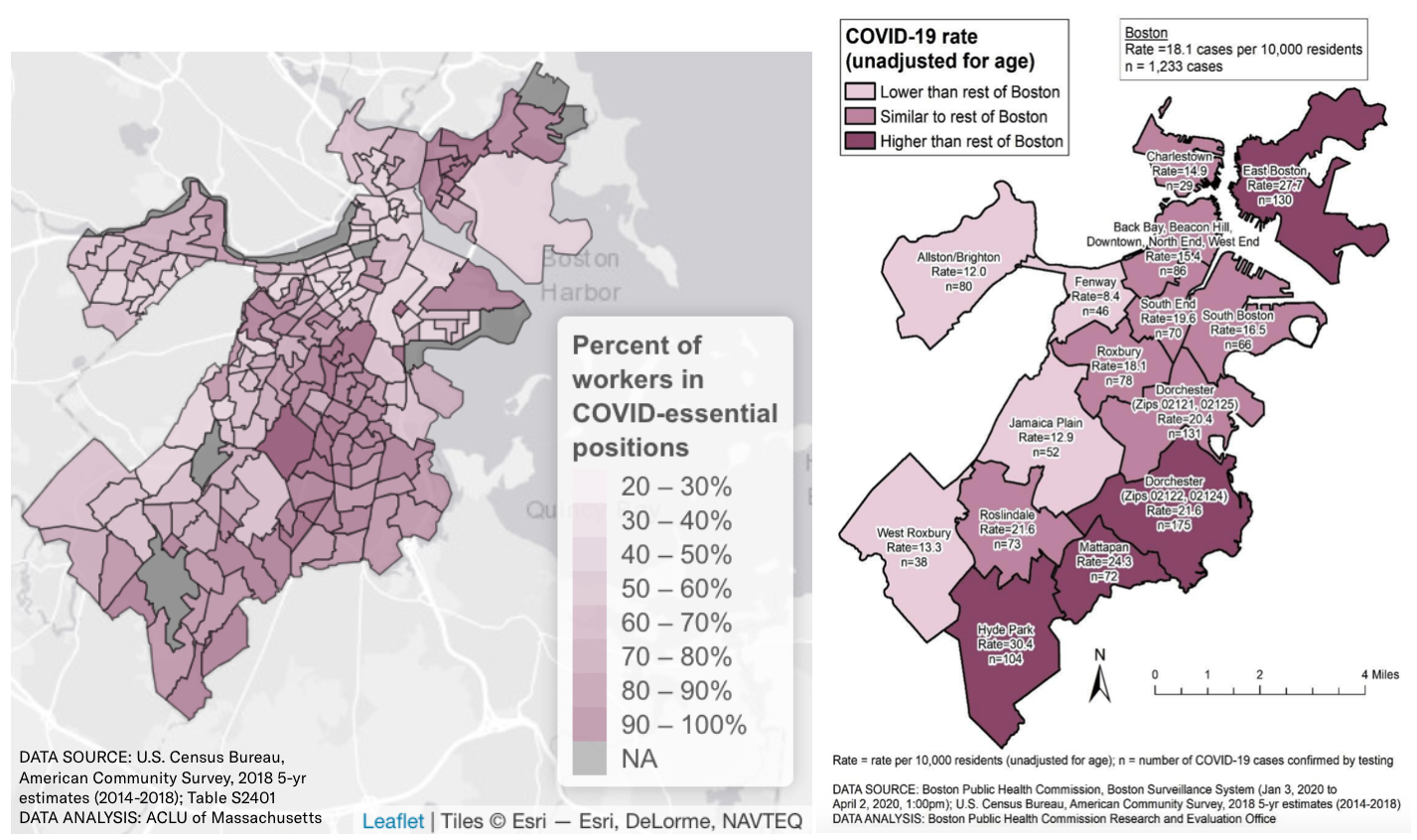

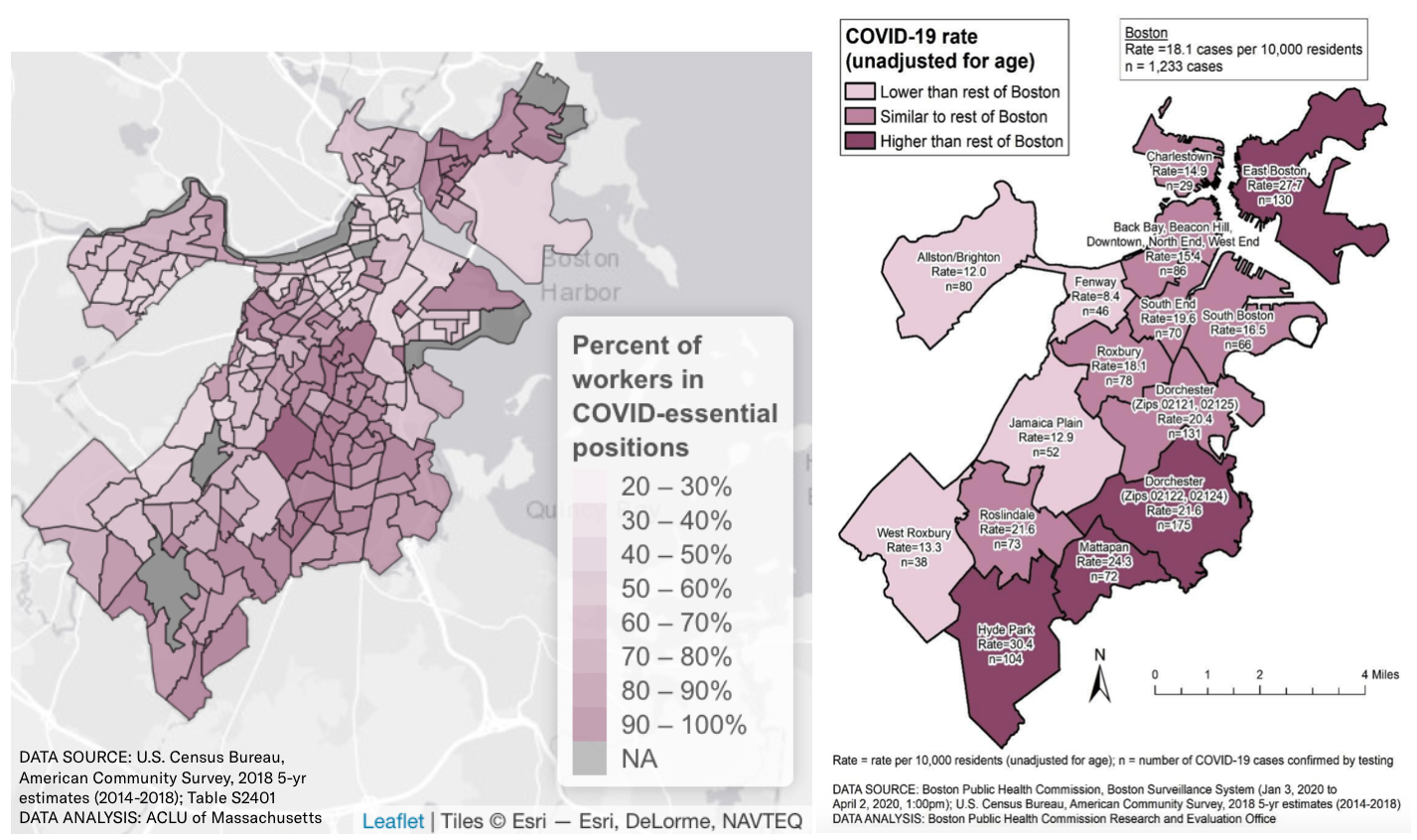

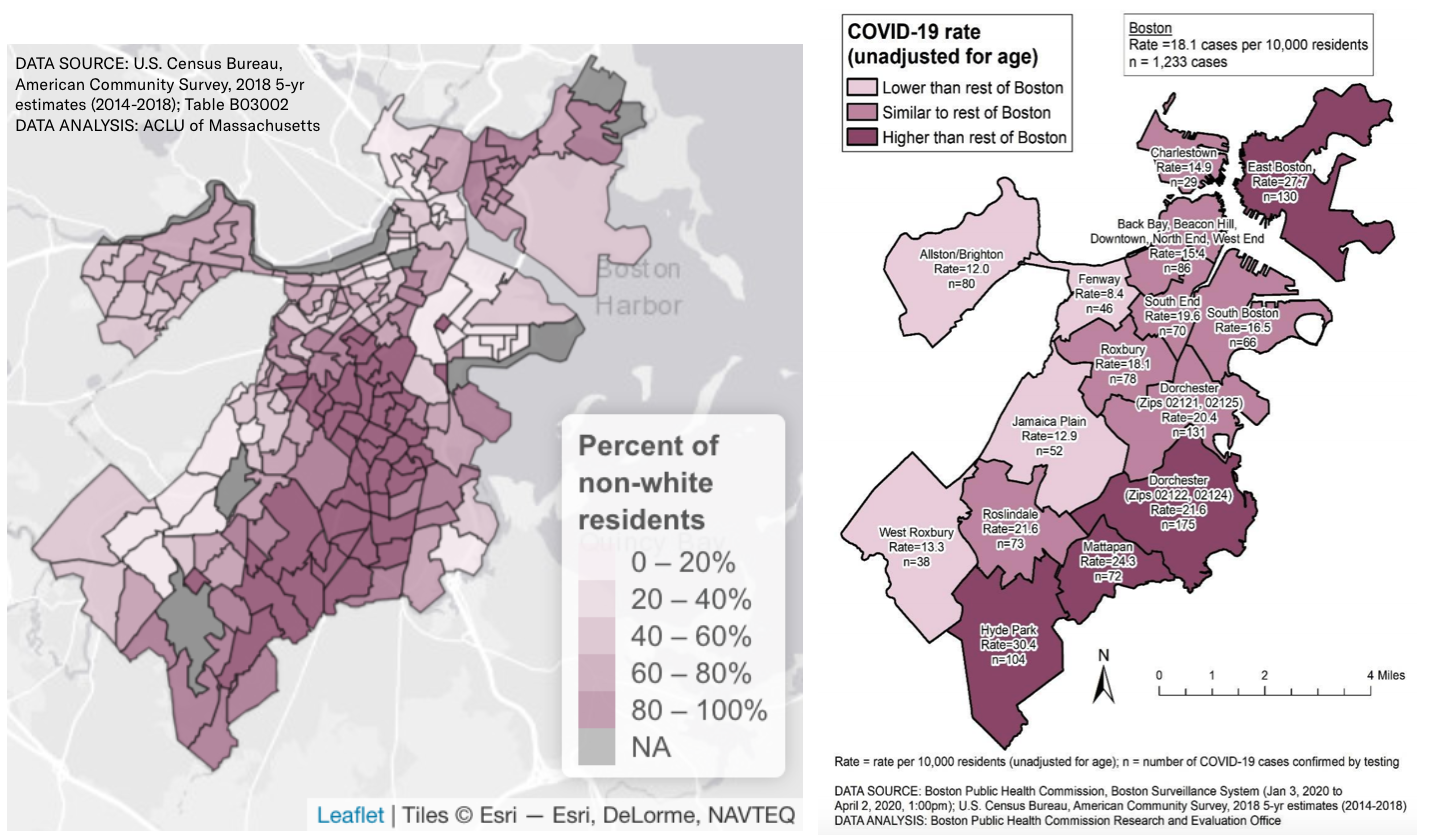

Data show COVID-19 is hitting essential workers and people of color hardest

Newly released data from the Boston Public Health Commission (BPHC) show that COVID-19 is present at higher rates in certain Boston communities, including Hyde Park, Mattapan, Dorchester, and East Boston. Analysis presented here by the ACLU of Massachusetts compares BPHC's findings to census data, in order to better understand how the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting Boston’s essential workers and communities of color.

COVID-19 Cases Concentrated Among Boston's Essential Workers

According to the census data, the Boston neighborhoods most impacted by COVID-19 are co-located with the highest proportions of essential workers in the city.

Using data from the U.S. Census 2018 American Community Survey (ACS), we mapped the proportion of workers across Boston who are employed in "COVID-essential" occupations. We defined "essential" occupations to include the following:

- Healthcare practitioners and technical occupations

- Construction and extraction occupation

- Farming, fishing, and forestry occupation

- Installation, maintenance, and repair occupation

- Material moving occupation

- Production occupation

- Transportation occupation

- Office and administrative support occupation

- Sales and related occupation

- Building and grounds cleaning and maintenance occupation

- Food preparation and serving related occupation

- Healthcare support occupation

- Personal care and service occupation

- Protective service occupations

COVID-essential workers are most concentrated in Dorchester, Roxbury, and East Boston – the same neighborhoods where the virus is present at its highest rates.

COVID-19 Cases Concentrated in Boston's Black & Brown Neighborhoods

Similarly, the areas with the most COVID-19 cases align with Boston's communities where people of color make up a majority of the population.

Communities like Hyde Park, Mattapan, and Dorchester where over 50 percent of the population is non-white (including African American, Hispanic or Latinx, Asian, Native American, Multiracial, or any racial category other than "White Alone") are again the same communities with the highest rates of COVID-19.

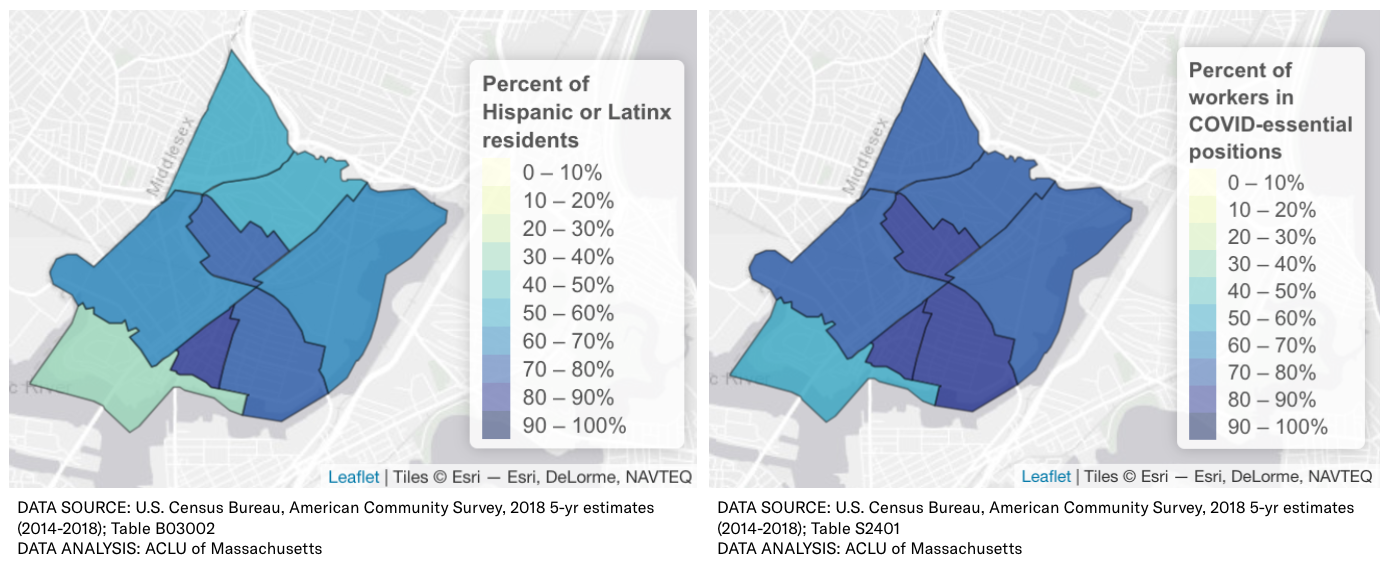

Latinx-Majority Chelsea Hit Hard

As this crisis evolves, more details are coming into focus that show how already-vulnerable communities are those hardest hit by the virus.

As of April 7th, the city of Chelsea had 315 COVID-19 cases in a population just over 40,000. This translates to a rate of about 79 cases per 10,000 residents – over four times higher than the rate in neighboring Boston of 18 cases per 10,000 residents, as reported by the BPHC.

On Monday evening, Massachusetts General Hospital's Chief Equity and Inclusion Officer, Dr. Joseph Betancourt, reported that 35-40 percent of the COVID-19 patients being treated at Mass. General were Hispanic or Latinx.

https://twitter.com/simonfrios/status/1247253763112517637?s=20

In an interview with WBUR, Betancourt mentioned that the outsized effect Chelsea is experiencing could be due to a number of factors, including increased rates of co-habitation and high proportions of residents working in jobs "where social distancing is not possible."

Indeed, our analysis of 2018 ACS data shows that 79.8 percent of all workers in Chelsea are in COVID-essential positions. In some parts of Chelsea, over 80 percent of the employed population work in occupations that are deemed essential during the on-going crisis:

And even within Chelsea, census tracts with the highest proportion of Hispanic or Latinx residents align exactly with the tracts containing the greatest percentage of workers employed in essential jobs.

As editorial writer Marcela García states in her recent Boston Globe piece about Chelsea, “Not only are these immigrants — mostly Latino, many of them here without legal status — the most economically vulnerable, but a high proportion of them already have limited access to health care and other public support networks. Working from home is a privilege that they simply don’t have.” She describes how the COVID-19 outbreak is acting as a “great revealer,” bringing to light systemic inequalities that have plagued minoritized and working-class communities for centuries.

Ultimately, it is communities like Chelsea, with a very high proportion of both COVID-essential workers and residents of color, that are suffering disproportionately in this pandemic. Ironically, a major cause of their increased hardship is the irreplaceable role they play in supporting the continued functioning of all of society, by working essential service jobs.

This is exactly why the ACLU of Massachusetts and other advocacy organizations are pushing for legislative, executive, and judicial action to protect immigrants and working people. While the federal stimulus package passed by Congress in March is a start, it does not go far enough to establish the comprehensive social and economic protections – or the robust data collection practices – required to support vulnerable communities across Massachusetts today.

Our mayors, governors, and representatives must step up. Last week, the ACLU of Massachusetts called on the state Department of Public Health to center equity in its response to the crisis. We must record the race and ethnicity of those receiving tests and treatment for COVID-19, so as to better understand how the virus affects different communities differently. We must ensure that our first responders—including not just EMTs and other healthcare personnel, but also grocery store employees, delivery workers, and public transit operators—have the personal protective equipment (PPE) they need, and have priority access to testing.

The stakes have seldom been higher to get it right on equity. Our leaders must act now in order to save the lives of those working to protect and support us all.

Interested programmers can find the R code used to create these maps on Github.

Edit: A previous version of this blog cited the total percent of essential workers in Chelsea to be 76.9 percent. That number was calculated in error, and has been updated to 79.8 percent.