Four county facilities with over 80 confirmed COVID-19 cases. Multiple county jails conducting fewer than 100 COVID tests over nine months. A 10 percent increase in individuals jailed before trial across the state.

Yesterday, together with the Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS) and the Massachusetts Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (MACDL), the ACLU of Massachusetts filed an amended petition in their existing case with the Supreme Judicial Court seeking relief for individuals incarcerated in county facilities who are currently threatened by the spread of COVID-19 across the state.

Almost nine months have passed since ACLUM first filed this lawsuit in late March, asking the Court to recognize the elevated risk that the pandemic posed to individuals incarcerated in both county and state facilities and to decrease the population of carceral facilities across the state. The Court’s ruling recognized the necessity of decreasing the incarcerated population, and ordered jails and prisons throughout the state to regularly report their population, releases, COVID-19 tests and results.

While yesterday’s filing focuses solely on county facilities, the data reported by both county and state facilities since April raise significant concerns regarding COVID-19 in carceral settings throughout the state.

An interactive dashboard created and maintained by the ACLU of Massachusetts presents weekly data reported by 19 facilities run by 13 county sheriffs (jails and houses of correction or HOCs) and daily data from 16 state Department of Correction (DOC) prisons – 35 facilities in sum. Analysis from the first week of reporting in April already demonstrated an inadequate COVID response in prisons and jails that, unfortunately, has continued for the better part of a year. Indeed, in recent weeks, advocates, attorneys, and worried family members have witnessed frighteningly low test rates, followed by outbreaks in over a dozen facilities – and now, deaths. Here we present four takeaways from recent trends.

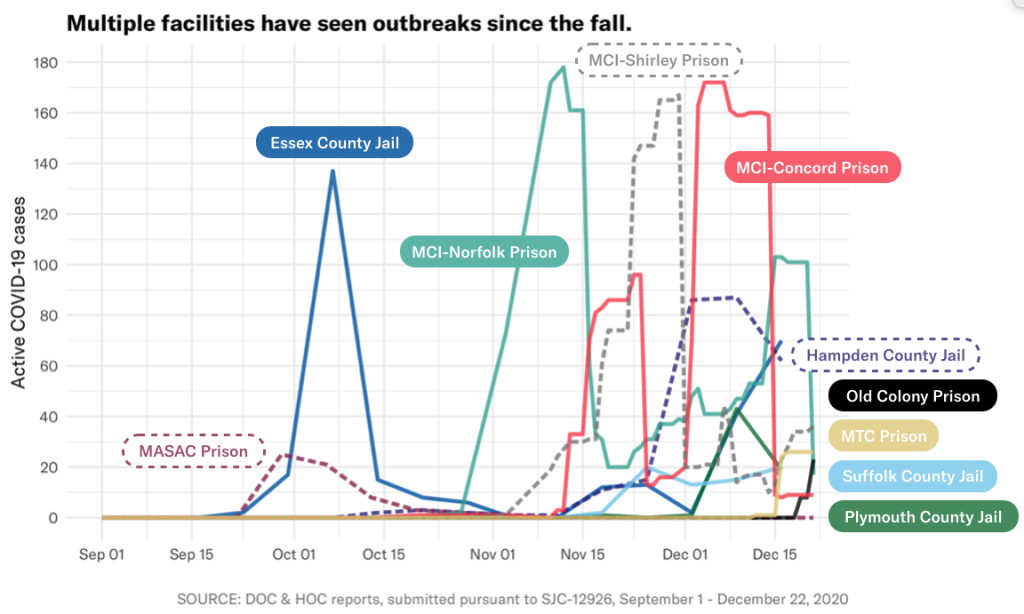

1. A battle against multiple simultaneous outbreaks

Since outbreaks of COVID-19 began increasing in Massachusetts in September, 27 prisons and jails statewide have seen more than 5 prisoners or staff infected with COVID-19. Seven facilities have seen more than 100 positive tests, and four facilities saw more than 100 simultaneous cases in a single outbreak.

In some state prisons, vast swaths of the facility’s prisoner population were (or are) infected at the peak of the outbreak, including: 33 percent of MCI-Concord (1 in 3) on December 7, 15 percent of MCI-Shirley on November 30, and 14 percent of MCI-Norfolk (1 in 6) on November 12.

| Facility Name | Positive tests (staff & prisoners), cumulative since Sept. 1 | Maximum active prisoner cases at peak of outbreak | Maximum active staff cases at peak of outbreak† |

| Barnstable County Correctional Facility | 10 | 0 | 9* |

| Bristol County Jail and House of Correction | 25 | 5 | 13* |

| Essex Middleton House of Correction | 257 | 137* | Not reported |

| Hampden County Correctional Center | 233 | 87 | 30* |

| Middlesex Jail & House of Correction | 46 | 9 | 26* |

| Plymouth County Correctional Facility | 123 | 43 | 35 |

| Suffolk South Bay House of Correction | 84 | 19 | 11 |

| Suffolk Nashua Street Jail | 41 | 17* | 8* |

| [DOC] Massachusetts Alcohol and Substance Abuse Center | 65 | 25 | Not reported |

| [DOC] MCI-Concord | 356 | 172 | Not reported |

| [DOC] MCI-Norfolk | 498 | 178 | Not reported |

| [DOC] MCI-Shirley | 337 | 167* | Not reported |

| [DOC] Massachusetts Treatment Center | 49 | 26* | Not reported |

| [DOC] North Central Correctional Institution | 228 | 83* | Not reported |

* – active positive cases stagnant or increasing as of December 22

† – no DOC facilities report active staff cases

The bottom line is that COVID-19 is raging across our jails and prisons, and the existing response is clearly proving inadequate.

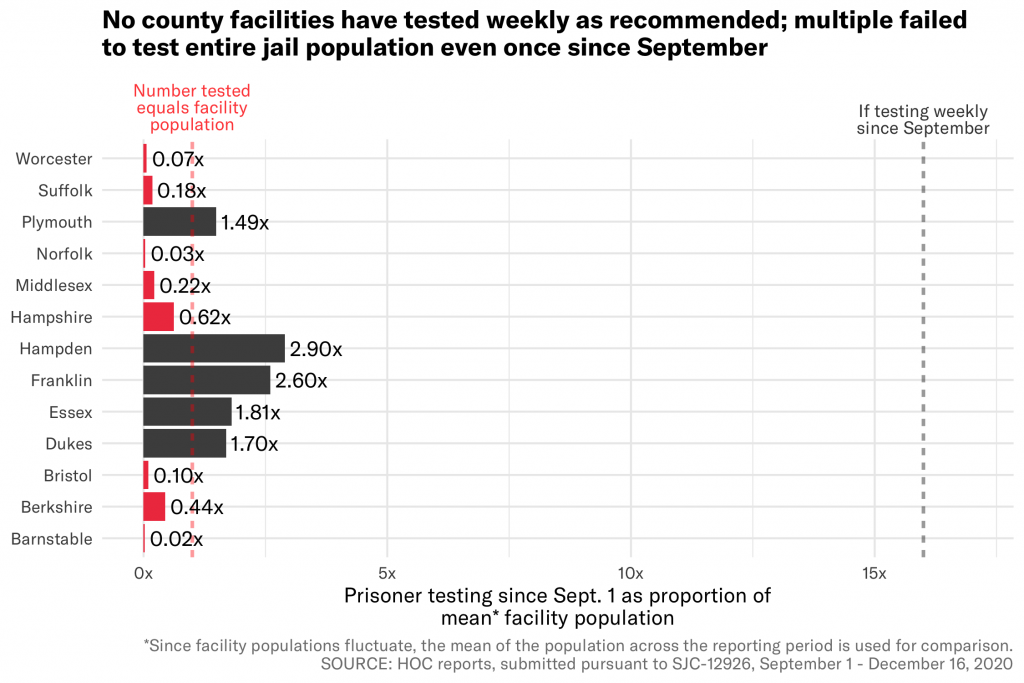

2. Testing has been consistently abysmal

There is a major and concerning caveat to available data on outbreaks: the numbers described above are just those COVID-19 cases that were confirmed via testing. Many prisons and jails are still not testing at a sufficient rate to detect and contain cases, and so there is reason to believe even the extreme outbreaks we’ve seen are underestimates.

Indeed, eight counties have not even conducted enough testing to account for their entire population once since outbreaks began accelerating in September. The most egregious examples include Barnstable County, which has conducted just 4 COVID tests since September while their prisoner population never dipped below 170and Worcester County, which has conducted just 39 COVID tests since September while their prisoner population never dipped below 566.

For comparison, Tufts University – which has a similar student population to the statewide prisoner population – has conducted almost as many tests in the previous 7 days (13,104) as all 13 county facilities have in the past nine months (13,562). And since August, Tufts has conducted more than 7 times as many tests (256,156) as all Massachusetts prisons and jails have since April (35,157).

And it’s not just private universities that are blowing jails out of the water; a state policy defined in June requires all staff at long-term care facilities to be tested weekly. The most recent state report showed that 407 of the 427 long-term care facilities in the state (95 percent) are currently compliant with this policy, as of the week of December 3-10.

The abysmal level of testing in jails is simply unacceptable, and they leave government officials effectively clueless as to whether new outbreaks are taking root across their facilities.

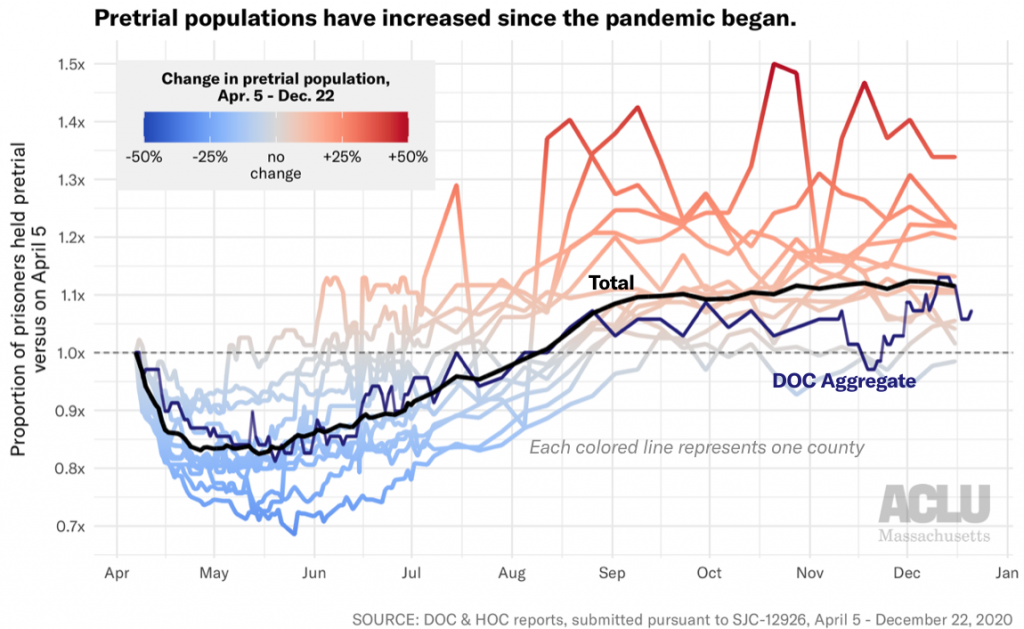

3. Rising prisoner populations increase danger

Yet testing is not the only preventative measure that prisons and jails have at their disposal, nor is it the only response that they are failing to properly implement.

One of the most effective measures to curb the spread of COVID is to reduce the population of incarcerated people – fewer people in cramped quarters reduces spread and saves lives. But concerningly, recent data show that many facilities are actually increasing their populations now, after a drop in the spring. And the population of those being held pretrial – people who have not been sentenced with a crime but are currently incarcerated – is actually higher today than it was at the start of reporting in April. Over 400 more people are currently incarcerated pretrial than nine months ago: 4,355 on December 16 compared to 3,928 on April 5.

Franklin County saw the largest proportional increase with a 34 percent jump in pretrial prisoners since April – from 62 to 83. In larger facilities, the raw difference is even more stark: Hampden County has 106 more prisoners held pretrial today than in April (+22 percent), Bristol County has 86 more (+20 percent), Essex County has 84 more (+13 percent) and Suffolk County has 75 more (+11 percent). And across all DOC facilities, we also see a 7 percent increase in pretrial prisoners, from 69 to 74.

Overall, while the statewide incarcerated population fell by over 2,000 in the first few months of the pandemic, the population has risen by 300 since the lowest point in late June. Rather than further stuffing already crowded carceral facilities, Massachusetts should instead be following in the footsteps of states like Colorado, which has reduced their jail population by 46 percent during the pandemic.

One available tool for decarceration is to release those prisoners who are statutorily eligible to home confinement. Recent analysis by CPCS estimates that approximately 427 prisoners held in county facilities as of December 11, 2020 were eligible for home confinement programs. However, three of the 13 counties do not even have a home confinement program, and those that do have such programs not used them to meaningfully reduce their populations. Indeed, as of November 5, 2020, a total of just 16 individuals were on home confinement from a county facility. Similarly, while the DOC has a home confinement program, available data show it has made no placements since at least .

Prisons and jails need to use every tool in their toolbox to protect those in their care, and decarceration is one of the most effective tools. Massachusetts must drastically step up its prisoner releases and decarceration efforts immediately.

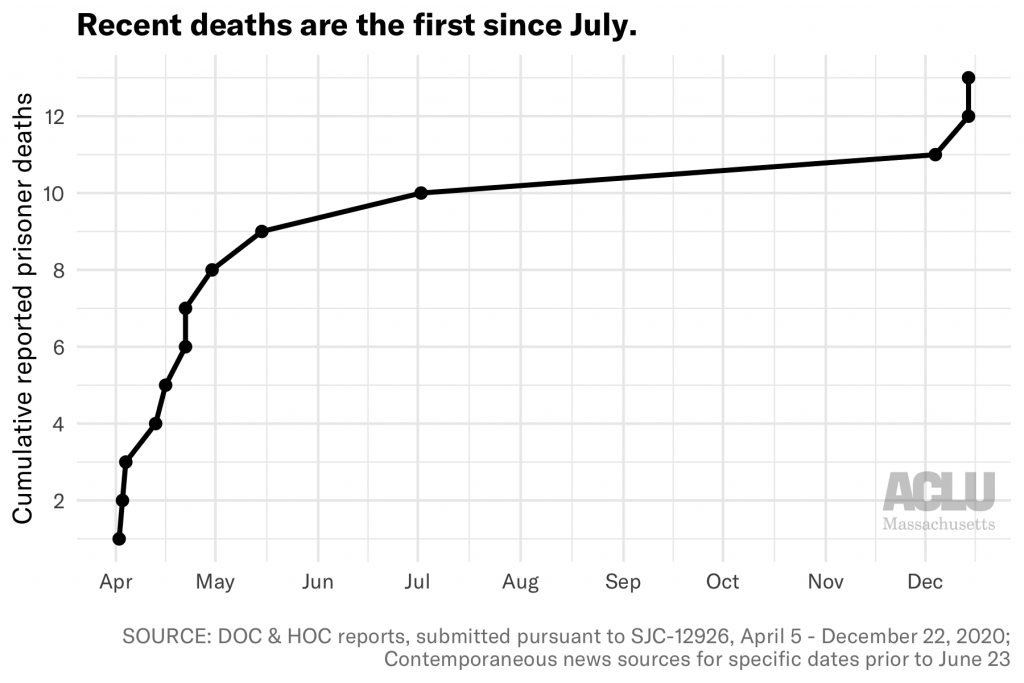

4. The consequences of inaction are fatal

Of course, these data on cases and positives represent human lives.

The DOC recently reported that a prisoner at MCI-Norfolk died from COVID-19 complications in their custody on December 4th. Two prisoner deaths were subsequently reported on December 14th, at MCI-Concord and MCI-Shirley. These reports come after the state saw no deaths for five months through the summer.

Furthermore, a shocking WBUR story in early December revealed that in at least two cases, the DOC approved medical parole for prisoners less than 24 hours before their death. Because these individuals were no longer technically in DOC custody, their deaths were not included in DOC reports to the petitioners.

One of these deaths was Milton Rice, a 76-year-old prisoner who had applied for medical parole in March, stating, “with my underlying health condition and compromised immune system issues, should I contract the COVID-19 virus it would more than likely be fatal for me.” He was finally granted medical parole on November 24, two weeks after testing positive, and he died of COVID-19 pneumonia on November 25 – the day before Thanksgiving.

As counsel in the SJC case wrote on March 24th, “There are about 16,500 human beings in our prisons and jails. None of them have been sentenced to death. Yet, without aggressive and immediate intervention, COVID-19 will likely kill many of them.” We have seen at least 13 deaths since then, with no appropriate response in sight.

The numbers presented here describe only the tip of an iceberg of an inadequate COVID-19 response. In a federal filing last month, Plymouth County Correctional Facility stated that asymptomatic staff at their facility were “not required to quarantine following an exposure to COVID-19.” One such staff member who returned to work tested positive less than a week later. Plymouth has since indicated that it has “resumed quarantining all close contacts and will only reduce the quarantine period in the future as required to maintain the safety and security of inmates and detainees.” Lockdowns, restrictions on visitation, and the use of solitary confinement as quarantine have been widely implemented – to the detriment of prisoners’ mental health over the past nine months. And throughout the pandemic, there have been reports from inside facilities of staff not consistently wearing masks or PPE.

Two weeks ago, Governor Baker’s office announced that Massachusetts will become one of the few states to include incarcerated individuals in Phase One of the statewide COVID vaccination plan. While this is an important and necessary measure for the future, it does not absolve the government of its responsibility to protect prisoners today; major changes are necessary to ensure that prisoners stay alive long enough to receive a vaccine. And for many, the vaccine will be too little and too late to right the wrongs affected by harmful policies over the past nine months. We know of at least 2,500 Massachusetts prisoners who have already been infected with this disease, and the consequences for their families and communities will be long-lasting.

Also two weeks ago, Governor Baker vetoed line item 8900-0001 from the proposed FY21 budget, which would create an independent ombudsman office to monitor COVID-19 in prisons:

Governor Baker struck all the language families of incarcerated people fought for to address the humanitarian crisis in MA prisons.

He has done absolutely nothing for our incarcerated loved ones nor our families. People are sick, suffering, dying.

Shame. Shame. Shame. #mapoli pic.twitter.com/DuxQBvUf4N

— Families for Justice as Healing (@justicehealing) December 11, 2020

The proposed office was a hard-fought victory by advocacy groups such as Families for Justice as Healing (FJAH), and already represented a legislative compromise. Unfortunately, this veto is just further evidence of the state’s failure to take sufficient action to protect those in their custody in the midst of this pandemic.

State and county governments in Massachusetts must take responsibility for the humanitarian crisis currently threatening – and killing – those in their care. They must drastically increase testing and both pretrial and post-conviction releases immediately, and provide more transparency on how vaccines will be distributed inside prisons and jails.

Take action:

- Use the Building Up People Not Prisons Coalition’s toolkit to contact your state legislators and urge them to override Baker’s veto of the correctional oversight office

- Use FJAH’s toolkit to contact the Department of Public Health commissioner and Department of Correction commissioner, urging them to reduce prison and jail populations and systematize COVID-19 testing