Data shows drug policing in Massachusetts overwhelmingly targeted drug users

Drug prosecution data released today by the ACLU of Massachusetts shows that police and prosecutors throughout Massachusetts arrested and prosecuted people for simple drug possession at alarming rates between 2003 and 2014.

For the first time ever, the ACLU of Massachusetts is publishing comprehensive drug prosecution data covering this time period, giving residents, researchers, policymakers, and advocates a clear picture of how the drug war unfolded in courtrooms across the state over a decade. The data shows that even as politicians and police shifted away from “tough on crime” language towards acknowledging addiction as a disease, large numbers of people nonetheless continued to face arrest, prosecution, and conviction merely for possessing drugs.

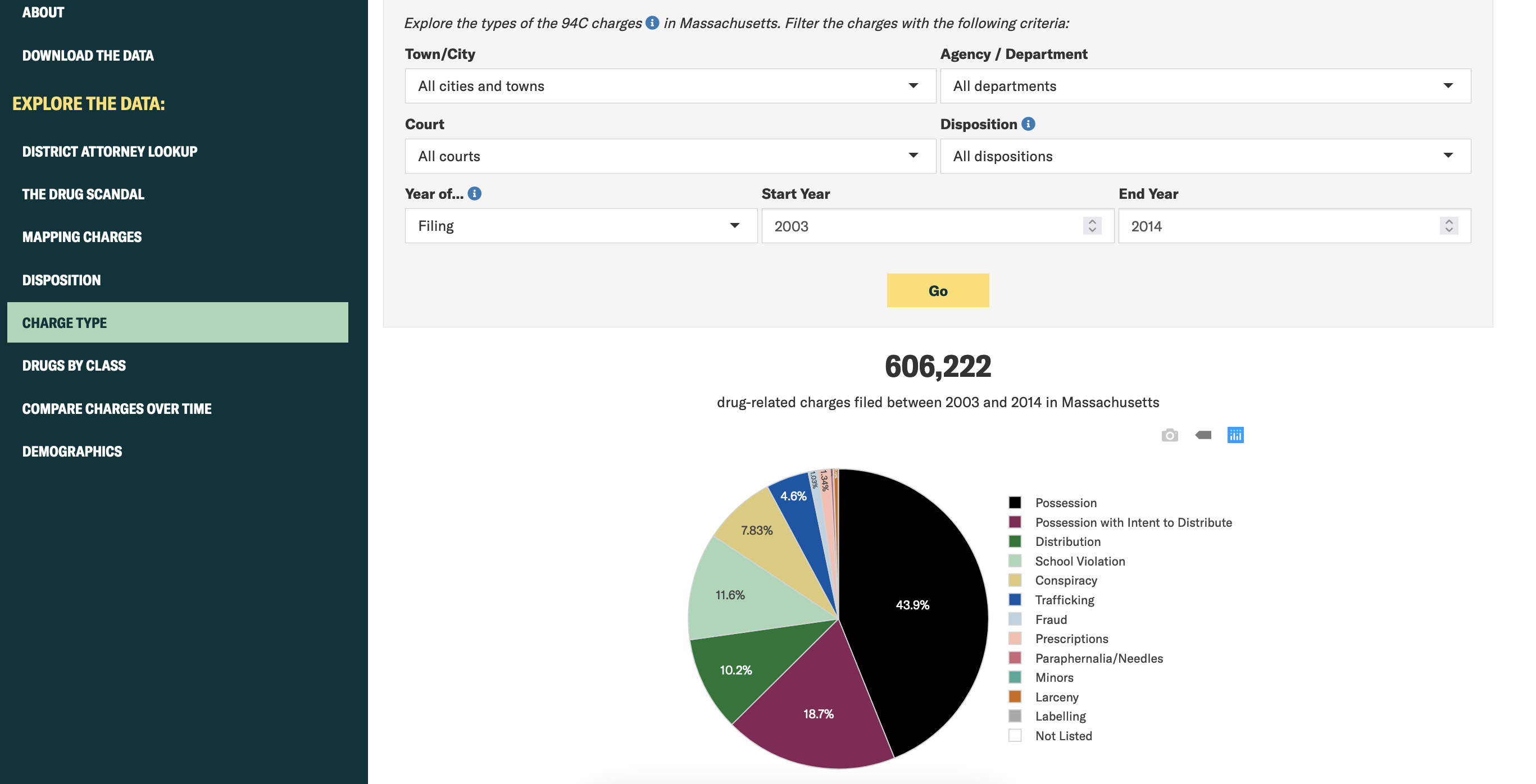

Of the over 600,000 drug charges filed against people in Massachusetts between 2003 and 2014, nearly half (44 percent) exclusively concerned simple possession. An additional 19 percent of charges were for “possession with intent to distribute,” a charge often leveled at drug users. In total, 63 percent of all drug charges in Massachusetts during this period were for possession or possession with intent to distribute, representing approximately 382,000 of the just over 600,000 drug charges filed against people during this time period.

While these low-level drug charges clogged up courtrooms across the state and burdened people with jail time and fees, most of these cases did not lead to a guilty finding. Only 19 percent of simple possession cases resulted in a guilty finding or plea. Forty-two percent were dismissed outright.

Likewise, only one in four of the over 100,000 prosecutions for possession with intent to distribute lead to a guilty finding or plea.

On the other hand, drug trafficking charges represented a tiny fraction of the overall war on drugs in our state. Just 5 percent of all charges dealt with this more serious offense category.

The data reveals striking differences in how police enforce drug laws across Massachusetts, showing that a handful of communities aggressively—and even exclusively—police drug possession. In eight rural communities in the western part of the state, every single drug arrest resulting in prosecution pertained to drug possession. On the other hand, in larger cities, drug possession prosecutions represented a smaller, though still troubling, percentage of the total. In Boston, for example, 35 percent of all drug prosecutions were for possession. In Worcester, the figure was 33 percent; in Springfield, it was 29 percent. One-in-three is nonetheless a disturbingly high rate, particularly given that big city police departments have significantly more resources and staff to investigate serious offenses.

In addition to providing new details about the policing and prosecution of drug possession across the state, the ACLU’s data explorer allows users to see how drug policing has changed over time, in individual communities and statewide. Another feature, “Drugs by Class,” breaks down drug prosecution data by drug type, showing how prosecutions of specific classes of drugs have changed over time. Users interested in how drug prosecution patterns vary in each county can explore details about how different District Attorneys pursued the drug war on the “District Attorney Lookup” page. The tool also provides key data about the impact of the drug lab scandal and related conviction dismissals, showing that contrary to claims from some prosecutors, the mass dismissal of tens of thousands of fraudulent drug convictions did not lead to increases in reported violent crimes.

The ACLU obtained the data from the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court during multi-year litigation arising from systemic government misconduct at two separate drug labs responsible for testing substances. The litigation ultimately led to the mass dismissal of tens of thousands of tainted drug convictions.

In Massachusetts, court data is not subject to the public records law, but the ACLU has asked the Massachusetts Trial Court to make drug prosecution data for the time period 2014 to the present available to us. We will update this tool if we receive it.

Special thanks to Lauren Chambers for building this interactive data explorer.

Break Up with the BRIC: Unpacking the Boston Regional Intelligence Center Budget

Explore all of the ACLU of Massachusetts' analysis on policing in the Commonwealth.

On Thursday, July 23, the Boston City Council is holding a hearing on three grants that would collectively approve over $1 million in additional funding to the Boston Police. These taxpayer dollars would go towards installing new surveillance cameras across Boston and funds for the Boston Regional Intelligence Center, or BRIC.

Thursday’s hearing is a re-run from a routine hearing which took place on June 4, in which the Boston City Council was slated to rubber-stamp these three grants - dockets #0408, #0710, and #0831. However, community advocate groups such as the Muslim Justice League rallied, urging the Councilors to be critical of – and ultimately reject – the BPD grants. Ironically, the BRIC representative failed to make an appearance at the hearing and the question of the grant approval was tabled for this future date.

Out-of-control funding of the Boston Police is nothing new - as discussed in an ACLU of Massachusetts analysis, in FY21 the initially proposed Boston Police budget was $414 million. Ultimately, the Boston City Council still approved $402 million for the BPD, despite thousands of constituents advocating for more substantial budget cuts.

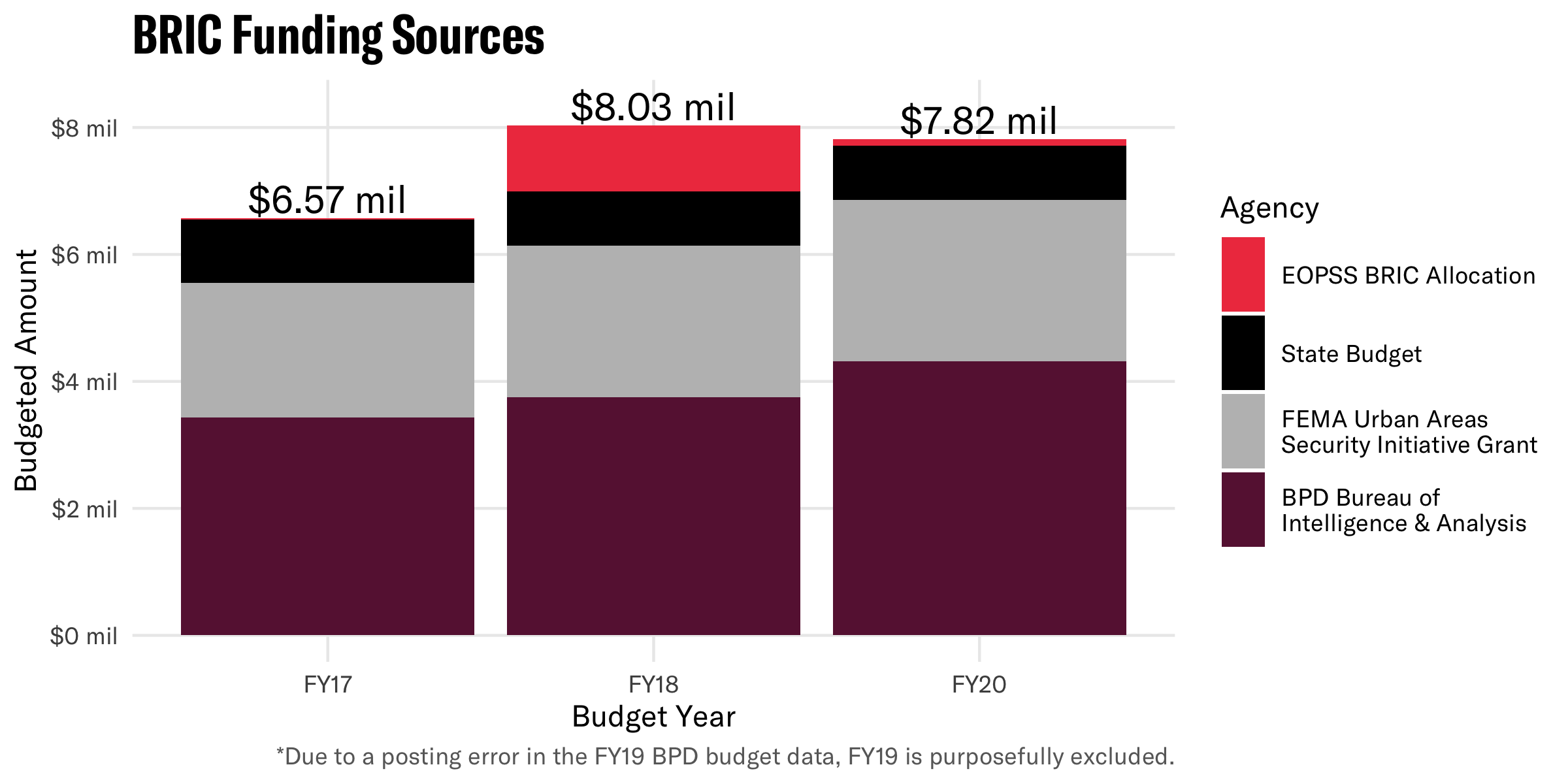

However, specific scrutiny of the BRIC and its funding is long overdue. In recent years, city, state, and federal legislatures have authorized well over $7 million in funding for the BRIC each year. But due to BPD secrecy surrounding all things BRIC-related, it’s hard to paint a full picture of what the BRIC does with this funding. Indeed, the description of the program on the Boston Police Department website consists of a mere 122 words - so we are forced to consult alternate sources and public records requests to get any details.

A new analysis of public records by the ACLU of Massachusetts takes a closer look at where the BRIC’s money comes from -- and what it’s used for.

What is the BRIC?

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is home to two federal fusion centers: Department of Homeland Security-funded centers established after September 11th, which facilitate information sharing between local, federal, and state law enforcement. One such center, the Commonwealth Fusion Center, is operated by the Massachusetts State Police, while the second, the Boston Regional Intelligence Center, or BRIC, is operated by the Boston Police Department.

The BRIC operates across the entire Metro Boston Homeland Security Region (MBHSR), which includes Boston, Brookline, Cambridge, Chelsea, Everett, Quincy, Revere, Somerville, and Winthrop.

Ample and Diverse Funding

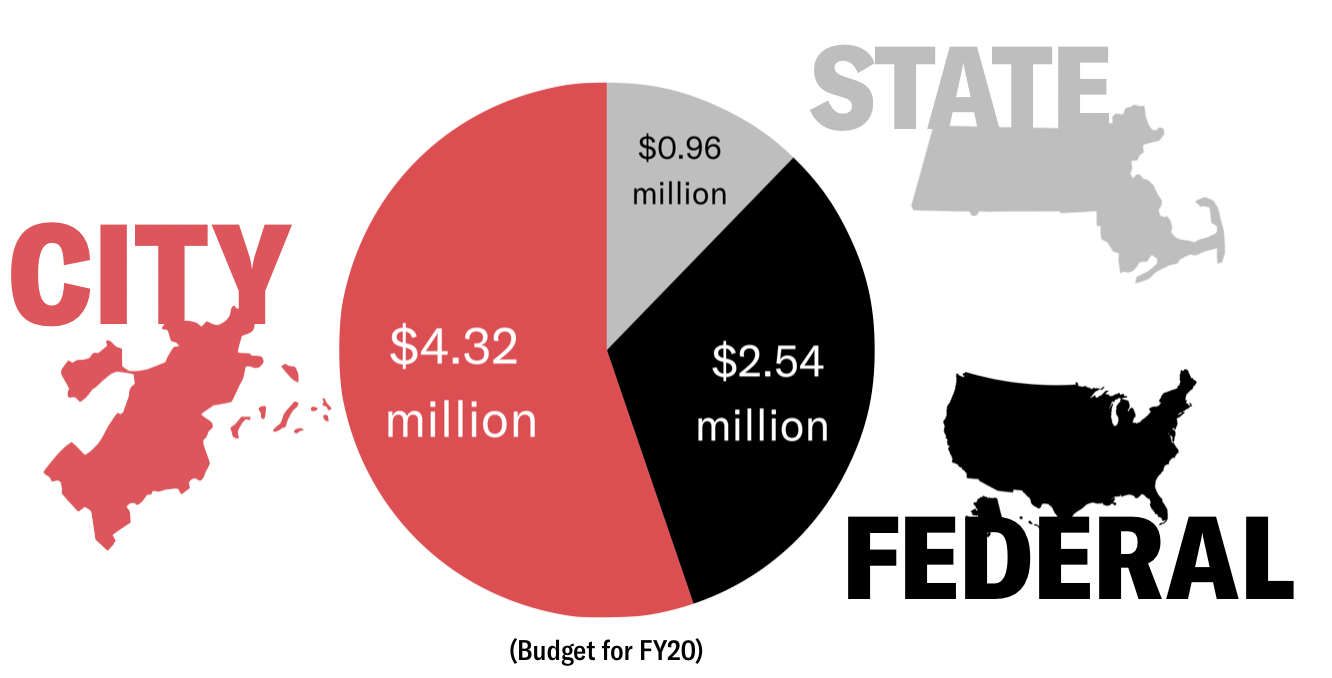

According to public records obtained and compiled by the ACLU of Massachusetts, the BRIC is funded by a combination of federal, state, and local budgets and grants.

Specifically, the BRIC receives funding from at least four distinct sources:

- Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Urban Areas Security Initiative (UASI) grants

- Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety and Security (EOPSS) yearly allocations, most likely from the DHS FEMA State Homeland Security Grant program

- Massachusetts state budgets (passed through the Executive Office of Public Safety and Security (EOPSS); line item 8000-1001)

- City of Boston operating budgets (via the Boston Police Department’s Bureau of Intelligence & Analysis)

These four funding streams combined lead to the BRIC receiving approximately $7-8 million each year in public funds.

Note that correspondence with the City of Boston revealed that publicly available data for the FY19 BPD Bureau of Intelligence & Analysis budget is incorrect due to a “posting error”, and so FY19 is excluded from all figures.

Additionally, it’s important to note that due to the lack of transparency, these four sources might not encompass all of the funding coming into the BRIC. For instance, a FY21 report of BPD contracts shows $4 million in payments for “intelligence analysts” to Centra Technologies between 2018 and 2021, likely working at the BRIC. If so, the BRIC budget may indeed be millions of dollars greater than what we are able to report today.

Who’s on the payroll?

How many people do work for the BRIC – and get their salaries from its budgeted funds? Ten? Sixty? It’s difficult to know.

Expense reports reveal at least 41 employees received training from the BRIC between 2017 and 2019 - but 10 of these names do not appear on the City of Boston payroll for those years.

Records show that the BRIC has some dedicated employees: in FY20, the personnel budget for the BPD’s Bureau of Intelligence and Analysis - whose sole charge seems to be the management of the BRIC - was $4.3 million. And in 2019, BRIC expense reports show $1.8 million in payments towards contracted “Intelligence Analysts” through companies such as Centra Technology, The Computer Merchant, and Computer and Engineering Services, Inc. (now Trillium Technical). But would this $1.8 million support 7 analysts making $250k per year? 30 analysts at $60k? The records do not provide clarity on this point.

Finally, confusion around one of the grants being discussed at Thursday’s hearing, proposed in docket #0408, further epitomizes the BRIC’s financial obfuscation around its payroll. The docket formally proposes $850,000 in grant funding to go towards “technology and protocols.” However in discussion at the June 4 hearing it was revealed that, in actuality, part of the grant would go toward hiring 6 new analysts.

By keeping under wraps the roles and job titles of BRIC employees, and even simply the size of the Center, BRIC obstructs transparency, public accountability, and city council oversight.

Hardware and Software Galore

Between 2017 and 2020, BRIC expense reports show the Center spent almost $1.3 million on hardware and software. Thorough review of these reports reveals exorbitant spending: on software of all flavors, scary surveillance technologies, frivolous tech gadgets, and some obscure mysteries.

A number of the expenses are clearly for surveillance cameras and devices, including $106,700 in orders for “single pole concealment cameras”. These pole cameras were bought from Kel-Tech Tactical Concealments, LLC, a company which also supplied the BRIC with some truly dystopian concealment devices such as a “Cable splice boot concealment” ($10,900), a “ShopVac camera system” ($5,250), and a “Tissue box concealment” ($4,900). These purchases imply the BRIC is hiding cameras in tissue boxes, vacuum cleaners, and even electrical cables.

Some of the charges on the report are just too vague to interpret. This includes the largest hardware/software charge in the entire report: $164,199 paid to Carousel Industries for “BRIV A/V Upgrade per Bid Event”. There’s $36,997 in “Engineering Support”, paid to PJ Systems Inc. and $15,606 in a “C45529 CI Technologies Contrac[t]”, paid to CI Technologies. And concerningly, there is a cumulative $16,200 in charges described simply as “(1 Year) of Unlimited” paid to CovertTrack Group Inc. – a company which also supplied the BRIC with a “Stealth 4 Basic Tracking Devic[e]” to the tune of $7,054.

When it comes to computing hardware, there’s no skimping either. Reports show over $200,000 in expenses for servers, and over $67,000 for various laptops. And apparently the BRIC prefers Apple products - judging by the $10,000 they spent on iPad pros, almost $1,000 on Apple Pencils, and $367 on Apple TVs.

Yet the most indulgent spending is on software. Between 2017 and 2020, the BRIC purchased at least 13 specialized software products for intelligence analysis, crime tracking, public records access, device extraction, and more.

| Software | Use | BRIC Expenses 2017-2020 |

| IBM i2 | “Insight analysis” | $124,852 |

| CrimeView Dashboard | Crime analysis, mapping and reporting | $58,009 |

| Accurint | Public records searches | $32,803 |

| Esri Enterprise | Geospatial analysis | $27,000 |

| Thomson Reuters’ CLEAR | Public records searches | $25,322 |

| CrimNtel GIS | Crime analysis, mapping and reporting | $21,016 |

| Computer-Aided Dispatch (CAD) Interface | Emergency response | $16,387 |

| Cellebrite Universal Forensic Extraction Device (UFED) Ultimate 4PC | Device data extraction | $12,878 |

| CaseInfo | Case management | $10,508 |

| NearMap | Geospatial analysis | $9,995 |

| ViewCommander-NVR | Surveillance camera recording | $3,778 |

| eSpatial | Geospatial analysis | $3,650 |

| XRY Logical & Physical | Device data extraction | $2,981 |

And worse, there is redundancy between the products - the BRIC purchased three different geospatial analysis products, two public records search products, and two device data extraction products.

This smorgasbord of tools begs the question: What, if any, supervisory procedures exist within the BRIC to prevent irresponsible spending of taxpayer dollars on expensive, duplicative software?

And furthermore, some of these public records databases give users immense power to access residential, financial, communication, and familial data about almost any person in the country. So who, if anyone, oversees the use of powerful surveillance databases like Accurint and CLEAR, to ensure they aren’t being used to violate basic rights and spy on ex-girlfriends?

From a history of First Amendment violations in Boston, to their role in threatening local immigrant students with deportation, to a 2012 bipartisan Congressional report concluding fusion centers such as the BRIC have been unilaterally ineffective at preventing terrorism, there is much evidence in support of the BRIC being wholly defunded. But at the very least, the Boston City Council must end the practice of writing blank checks for the Boston Police to continue excessive and unscrutinized spending of taxpayer dollars.

The Boston City Council must reject the additional $1 million in funding to the Boston Police being proposed in these three grants. To learn more about the BRIC, the proposed grants, and to urge the City Council to reject them, we encourage you to:

- Consult the Muslim Justice League Toolkit to Get the BRIC Out of Boston

- Sign a petition telling Boston City Councilors to reject BRIC-related grants before Tuesday, July 28

- Submit written testimony for the BRIC budget hearing before 9:30 AM on Saturday, July 25, telling Boston City Councilors to reject BRIC-related grants

Bond Bill Funds Prisons and Police over Education

Editor's Note: Today, the Senate Bonding Committee gave S2579: the General Government Bond Bill (previously H.4733) a favorable report. Last week, the committee on Senate Bonding, Capital Expenditures and State Assets concluded hearings on this bill. We are glad to see that the committee added limiting language to ensure that the $150 million authorization for public safety facilities would not be spent on building new prisons or jails. As the bill advances to Senate Ways and Means, we hope to see more amendments that prioritize investment in communities rather than policing and prisons.

What is the “General Government Bond Bill” and why should we care?

Last week the committee on Senate Bonding, Capital Expenditures and State Assets concluded hearings on H.4733, the General Government Bond Bill (originally H.4708). This Bond Bill intends to finance general governmental infrastructure of the Commonwealth around “public safety, information technology and data and cyber-security improvements.”

Bond bills are borrowing bills which pass on not just debt to future generations but also values. Given the huge disparities the pandemic has both exposed and created through mandatory remote learning, the top priority for any debt for future taxpayers should in fact be their current education. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown how crucial basic broadband infrastructure is to ensure equitable access to education. Education Commissioner Jeff Riley testified last month to the need of $50 million to support MA school districts to reach students without internet access (9% of students) or exclusive use of a device (15% of students).

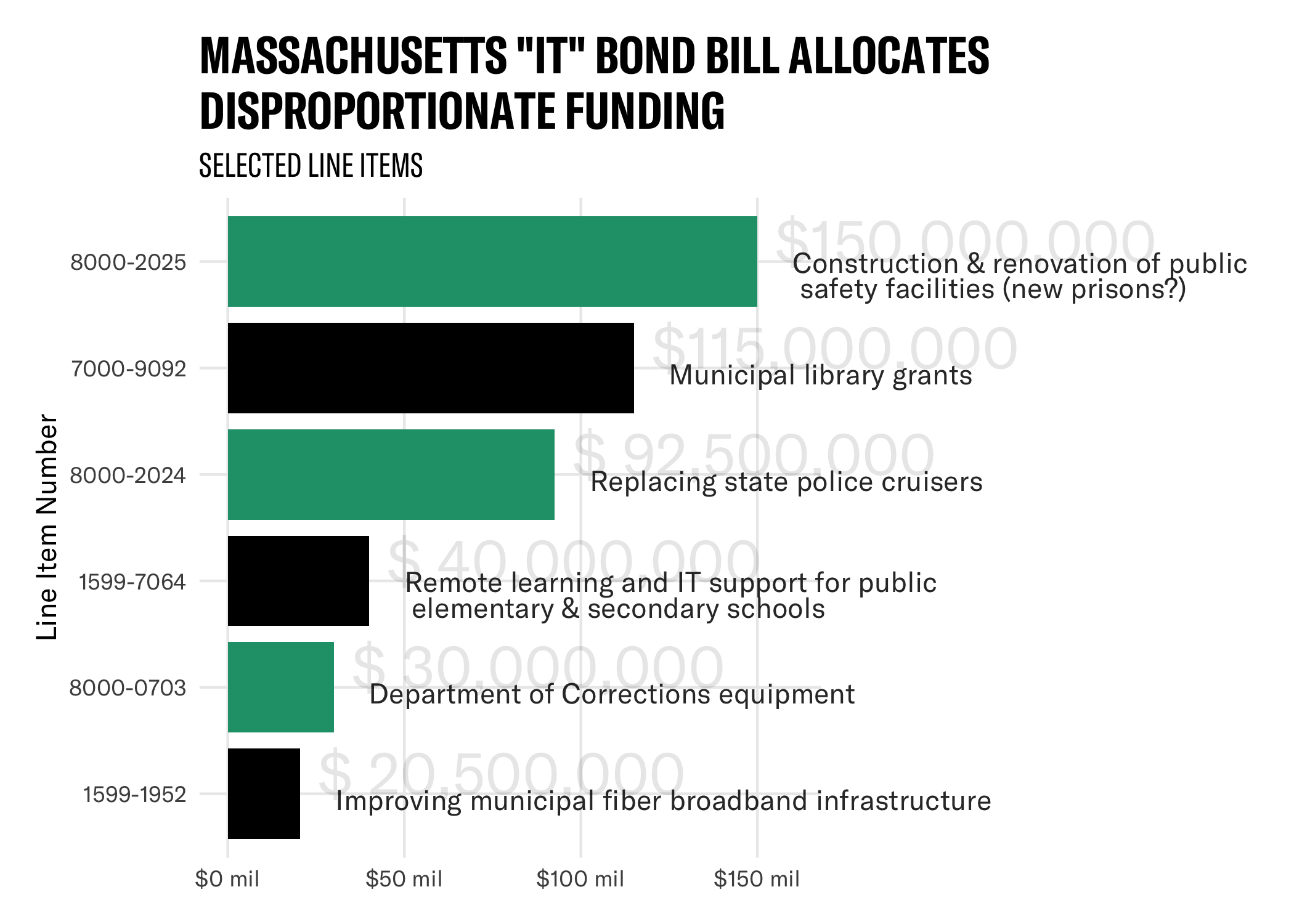

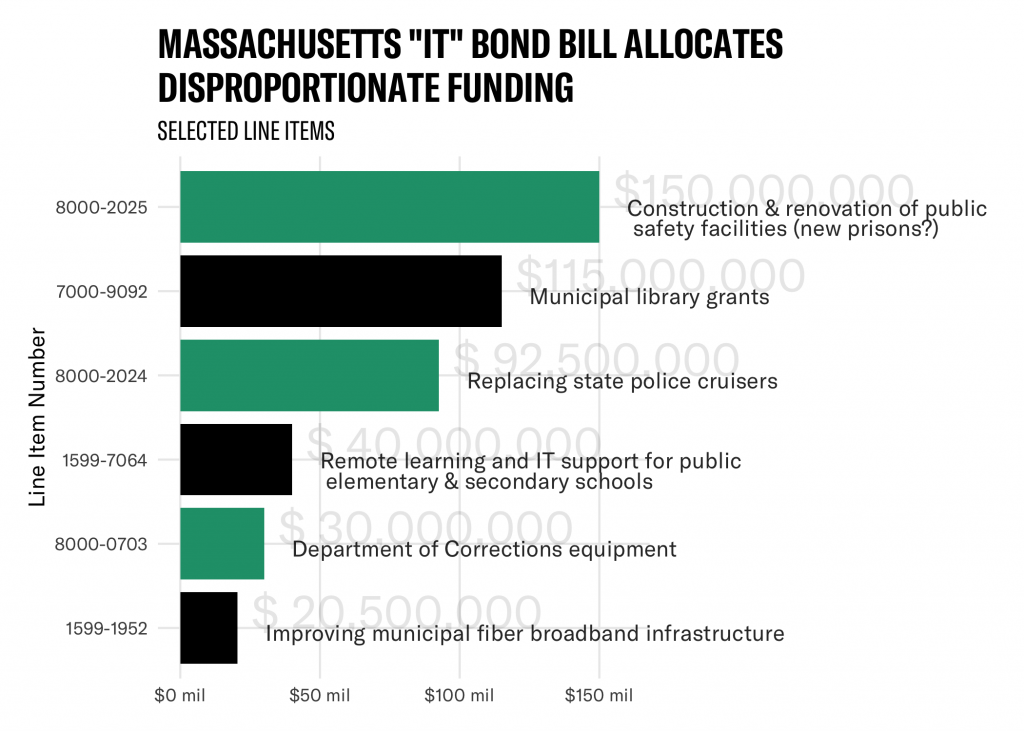

Instead, this bill allows for at least $270 million to build prisons, acquire police cruisers and other equipment for the Department of Corrections. The events of the last few weeks have shown the unnecessary, unwise, and unjust investment in the criminal legal system -- a system that over-polices, over-prosecutes, and over-incarcerates Black and Brown communities in the Commonwealth. The bill’s funding priorities need to be flipped.

As the Boston advocacy organization Families for Justice as Healing states in their call to action against H.4733, "The Commonwealth already spends more money per capita on law enforcement and incarceration than almost any other state. Communities need capital money for critical infrastructure projects like housing, carte facilities, parks, schools, treatment centers, healing centers, community centers, and spaces for art, sports, and culture."

Why are we still investing in police and prisons?

Over the last week, the world has watched as protests against police brutality and unaccountability have been met with further use of excessive force on protestors. As we live through the historic Black Lives Matter movement, the ACLU of Massachusetts (ACLUM) has joined the calls of Black and Brown-led organizations to divest from police in favor of investments in systems that support, feed, and protect people.

There have been demands from across the country to defund police departments, with the Minnesota City Council declaring its intent to disband the police department all together. The timing of further funding of police departments is incomprehensible at this watershed moment for racial justice across the country and in the midst of an economic freefall due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bond bill H.4733 does not meet this moment. In testimony to the Senate Committee on the Bond Bill, ACLUM strongly opposed line item 8000-2025, which would authorize an enormous amount of borrowing to build prisons. Families for Justice as Healing also opposed this line item, testifying that "significant decarceration is possible and further decarceration is doable and practical under current law, and at a cost-savings to the commonwealth."

ACLUM also opposed line item 8000-0703, authorizing the borrowing of $30 million for the purchase of Department of Corrections and Executive Office of Public Safety and Security for equipment and vehicles, and line item 8000-2024, authorizing the borrowing of $92 million for the purchase of police cruisers. (This is enough to put over $40,000 towards a new or improved car for all 2,199 Massachusetts State Police employees.)

Even without bond funds, police departments across the Commonwealth and the country are incredibly well funded. As previous ACLUM analysis of the City of Boston budget on Data for Justice shows, compared to the budgets of other Boston City departments (and cabinets), the Boston Police budget is exponentially higher than that of community focused organizations like Library, Neighborhood Development and Office of Arts and Culture.

Why aren’t we investing in actual information technology infrastructure?

Instead of authorizing new debt to build prisons and increase police budgets, we should be investing in information technology to support educational equity throughout the Commonwealth. In that way, this bond bill could truly reflect values we want to pass down to our children.

At present, the line item 1599-7064 is the only one which directly does this, authorizing $40 million to help close the digital divide for students in the Commonwealth. Certain emergency measures have been taken by school districts to enable transition to remote learning such as tablets and free access to assistive technology. However a bill that is intended to finance the general governmental infrastructure of the Commonwealth, and in particular to provide assistance to public school districts for remote learning environments, should invest in more than $40 million in state-wide digital infrastructure to permanently close the digital divide.

What exactly do we need to invest in?

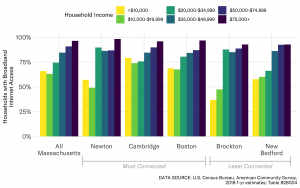

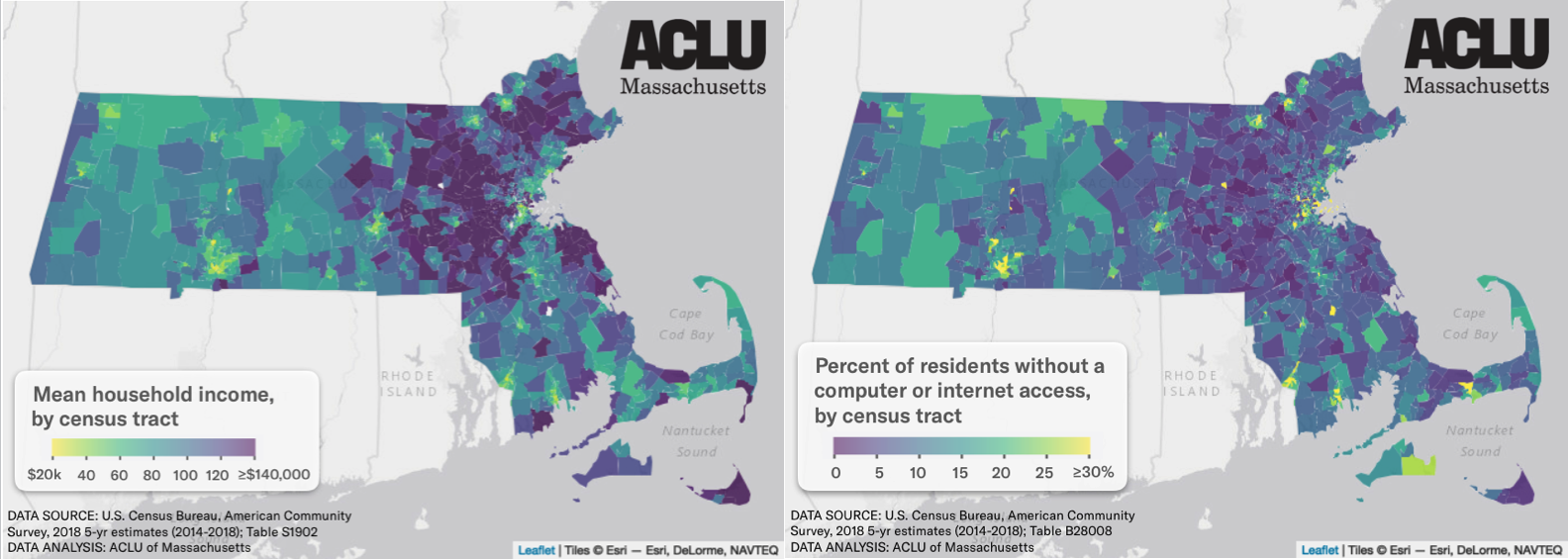

Data from the United States Census American Community Survey show that about 8% of households either do not have a computer, or if they do, do not have access to the internet at all. Furthermore, more than 1 million Massachusetts residents (> 15%) do not have a fixed broadband internet connection.

As reported in a previous analysis by the ACLU of Massachusetts, lower rates of internet access or broadband correlate with lower income, both in terms of macroscopic geography (e.g. southern and western Massachusetts), and low-income neighborhoods within cities. 8 cities in Massachusetts have at least 30% of households without cable, DSL or fiber Internet subscriptions in 2018 - Fall River, Springfield, Lowell, Lawrence, Worcester, Lynn, New Bedford and Brockton.

Taking a closer look at Brockton for example: of the households in the lowest two income categories, less than 50 percent have broadband internet access. This is similar to the pattern of better connected cities such as Newton. Here too, about 50 percent of households in the lowest two income categories do not have broadband. Thus from the perspective of a household, one's income is a stronger indicator of access to the internet, even if one is living in an area which generally has robust high speed internet connectivity.

Divest - Reinvest

Bond bill H.4733 singles out certain cities for specific projects. Brockton, for example, is slated to get $2,000,000 for enhanced security camera systems at public housing buildings Campello and Sullivan towers. Instead of investment in broadband, Lawrence, which ranks 28th on the list of 623 worst connected cities in the country, is going to get $2,500,000 for police cruiser technology.Thankfully Springfield, ranked 24 on that list, is slated to get $7,500,000 for a citywide fiber network.

Beyond Education Commissioner Jeff Riley’s testimony on the need of $50 million for remote elementary and secondary education, State and community colleges are in dire need of funding as well. The community colleges’ chief financial officers recently tallied the costs of additional information technology at nearly $17 million.

Rather than expanding the racist carceral state, we should use this Bond Bill to create equitable digital infrastructure to even out the playing field for the future generation.

Declining to Prosecute in the Interest of Racial Justice

Suffolk County’s reform candidate for District Attorney (DA) said declining to prosecute lower-level crimes would advance racial and economic justice. Police lobbies warned of chaos. Newly published records obtained by the ACLU show then-candidate Rachael Rollins was right—ending the prosecution of low-level crimes would disproportionately benefit Black people. Crucially, the data also show that her plan isn’t such a radical departure from the prior DA’s charging patterns.

During the 2018 electoral campaign for Suffolk County District Attorney, Rollins took a bold step that may have secured her the Democratic Party nomination, and later, the seat. Following other progressive-minded reform DA candidates like Philadelphia’s Larry Krasner, Rollins released a list of 15 misdemeanors and low-level felonies that, if elected, her office would “decline to prosecute.” Her pledge was hailed by progressives and criminal legal reform advocates, but sharply criticized by police lobby groups and others in law enforcement.

In fact, data from DA Dan Conley’s term in office reveal that Rollins’ plan won’t mark a sea change for the Suffolk County DA’s Office. The data show that over half of the charges Rollins has indicated her office will decline to prosecute were dismissed under Conley.

The revelation that DA Conley dismissed more than half of these types of low-level cases comes in a new report by the ACLU of Massachusetts, Facts Over Fear: The benefits of declining to prosecute misdemeanor and low-level felony offenses. The analysis uses empirical data to evaluate how, over a two-year period, DA Conley prosecuted people in Suffolk County for the low-level offenses Rollins has indicated her office will decline to prosecute.

The information, obtained by Boston resident Carol Pryor through a public records request and shared with the ACLU, is a list of every charge processed to a disposition by the office in 2013 and 2014. The records include race information about the people charged.

The report has two main findings:

1. DA Rollins’ plan addresses racial inequity in the criminal legal system.

The data indicates that if DA Rollins fulfills her campaign promise to decline to prosecute these 15 lower-level offenses, it will have a disproportionately positive impact on Black people in Suffolk County, who during Conley’s time in office were disproportionately charged with the misdemeanors and low-level felonies DA Rollins has pledged not to prosecute.

For example, under Conley, Black people were three times more likely to be charged with disorderly conduct or trespassing than white people, per capita. In some geographic jurisdictions of the Boston Municipal Court system, the disparities were even starker.

Racial disparities in charging data suggest racial bias in policing practices. Declining to prosecute misdemeanors and low-level felonies can be a check on racially disparate policing.

In the map above, mouse over a division of the Boston Municipal Court (BMC) system to learn more about the cases or charges processed in that division. Select the “Ratio of Black to White People” view to see how many more times Black people were likely to be arrested and charged with a driving, trespassing or drug possession with intent offense, compared to white people. This map shows per capita racial breakdowns by BMC district.

2. DA Conley dismissed most cases involving one of the offenses Rollins has said her office won’t prosecute.

“Decline to Prosecute” cases—or cases that contain at least one decline to prosecute charge—make up about 37.7 percent of the 49,033 total cases processed by the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office in those years. Of that 37.7 percent, 55 percent of these cases have a non-adverse (dismissed or equivalent) outcome.

In Massachusetts, advocates have been demanding reforms to a system that disproportionately over-polices, over-charges, and over-prosecutes people of color. Black and brown people in Suffolk County have born the weight of fear-based tactics that presume the worst of people and disrupt countless lives. We need data-based solutions that are rooted in restoration, transformation, and healing. A small step forward is declining to prosecute these lower-level offenses. The data show us that doing so is an important—yet hardly radical—step forward for racial justice.