Eyes in the Sky: Massachusetts State Police Used Drones to Monitor Black Lives Matter Protests

Records obtained by the ACLU of Massachusetts reveal the State Police routinely fly drones over the Commonwealth, for a variety of purposes, without warrants.

During the summer of 2020, as the nationwide movement against systemic racism grew in the wake of the police murder of George Floyd, the State Police here in Massachusetts (MSP) were busy sending drones to quietly monitor Black Lives Matter protesters across the state.

Records obtained by the ACLU of Massachusetts show the MSP used aerial surveillance to track protests occurring in Fitchburg, Leominster, Gardner, Worcester, Agawam, and Boston. While internal police reports say police did not (in most cases) retain pictures or videos of the protests, the video feeds were streamed in real time to local police departments and the State Police Fusion Center for “situational awareness.”

The records also reveal that the MSP has participated in trainings facilitated by Dave Grossman, a former Army Ranger turned police trainer who has faced extensive criticism for his violent rhetoric. Grossman is infamous for teaching police what he calls “killology,” a so-called “warrior mindset” for officers.

Records obtained by the ACLU last year from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) show drones are in use by police departments across the state. Unlike other aerial surveillance technologies such as helicopters and spy planes, drones are easy to deploy, cheap, small, and quiet to operate. According to FAA records, the MSP owns 81 drones—making its program the largest law enforcement drone operation in the state.

The ACLU of Massachusetts filed several public records requests to understand how the MSP uses drones. In response to a request asking for records about drone use since 2020, the MSP told us there were almost 200,000 relevant records. Unfortunately, the MSP asked us to pay for most of them, amounting to a sum we could not afford. After negotiating with the agency, we agreed to narrow our request in the following way. We asked for (i) emails and reports for the time period between May 29, 2020 to June 15, 2020 and (ii) additional reports for the period between January 20, 2022 to May 24, 2022. This resulted in the disclosure of hundreds—instead of hundreds of thousands—of pages of documents. What we obtained therefore only opens a small window onto the MSP’s drone program, but the records nonetheless provide important information about how the MSP uses their drones.

How did the MSP acquire a drone fleet?

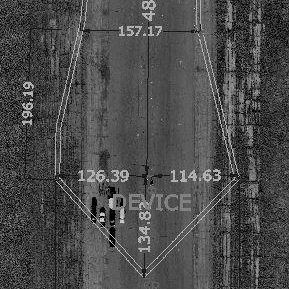

According to the records, as of October 2022, the department had 22 drones, including the following makes and models:

- Four Mavic 2 Hasselblads

- Three Mavic 2 Enterprise Duals

- Two Sparks

- Three Matrice 300 RTKs

- Eight Mavic Minis

- One Phantom 4 Pro+

The two most advanced drones are the Mavic 2 Enterprise Dual and the Matrice 300 RTK.

- The Mavic 2 Enterprise Dual: This powerful drone has thermal imagery capabilities, an integrated radiometric thermal sensor, adjustable parameters for emissivity and reflective surfaces, and multiple display modes.

- The Matrice 300 RTK: This is also a very advanced model—at the time of writing, the latest one released by the manufacturer DJI—offering up to 55 minutes of flight time, machine learning technology that recognizes a subject of interest and identifies it in subsequent automated missions to ensure consistent framing, six directional sensing and positioning, and 15km-1080p map transmission.

The records show the federal government financed the expansion of the MSP drone program, with the state government as an intermediary. In 2019, the MSP received an award of $99,011 from the state government to purchase drones. The funding came from the Homeland Security Grant Program, a Department of Homeland Security funding stream available to all states. This federal funding, passed through the state, allowed the State Police to purchase nine drones from a company called Safeware.

The MSP’s drone policy

The MSP also produced a policy to govern the department’s use of drones. The policy includes some important civil rights protections, but needs substantial work. And crucially, an ACLU review of records provided by the MSP indicates the department’s compliance with the policy appears to be inconsistent.

The policy establishes that drones may be used for a list of purposes that is far too broad, leaving the door open to abuse and misuse. The policy should explicitly list all permissible purposes for drone use. Instead, it takes an open-ended approach. For example, the records show “Homeland Security” is listed as a permissible purpose for drone usage. But this vague phrase is open to extremely broad interpretation, and could be used to justify drone usage in almost any scenario.

The policy states that the drone program is operated by the Unmanned Aerial Section of the Homeland Security and Preparedness division of the MSP. But “Homeland Security” has nothing to do with the vast majority of enumerated purposes listed in the policy, such as accident reconstruction, missing persons investigations, and criminal investigations surveillance. It is likely that the “Homeland Security” division is in charge of the drone program simply because the money for most of the drones came from the federal DHS, not because the drones are actually used in operations relative to “homeland security” operations.

The policy requires police to obtain a warrant or court order to use a drone in a criminal investigation, where a person has a reasonable expectation of privacy (except in exigent circumstances). However, in response to our requests, the MSP did not produce a single search warrant, indicating that the department has never obtained one to use a drone for surveillance purposes. There could be several reasons for this. It’s possible that police are: 1)simply not using drones in criminal investigations, 2) using them without a warrant in violation of the policy, 3) defining “reasonable expectation of privacy” too narrowly, or 4) simply using drones only to investigate criminal activity when exigent circumstances make getting a warrant impractical. Regardless, the fact that the MSP has never once obtained a warrant to use a drone indicates that the policy does not offer sufficient privacy protection. This suggests that we need a law on the books to enforce our rights.

Current privacy protections are not enough

To the MSP’s credit, their policy incorporates the principle of data minimization. This means that in order for any data to be collected with a drone, that data must be essential to complete the objective of the drone mission. Additionally, the policy states that drones cannot be paired with facial recognition technology to identify individuals in real time, and may not be used to carry weapons or facilitate the use of any weapons and/or dispersal payloads. These are important protections, and the ACLU applauds the MSP for including them.

That said, other language in the policy meant to protect civil rights and civil liberties is weak. For example, the policy forbids police from using a drone to target a person based solely on individual characteristics such as race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, disability, gender, or sexual orientation. But the inclusion of the word “solely” leaves open the possibility that the police will target someone in part on the basis of a protected characteristic like their race or national origin.

Likewise, the policy forbids the collection, use, retention, or dissemination of data in any manner that would violate the First Amendment or in any manner that would unlawfully discriminate against persons based upon their ethnicity, race, gender, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, or gender identity. But case law is underdeveloped and insufficient in these areas, leaving decision making about what constitutes a First Amendment violation or discrimination up to the police. Instead, the language should clearly stipulate that the MSP shall not use drones to monitor people exercising their First Amendment rights to assemble, petition the government, exercise their religion, or protest.

Instead, the policy allows drone footage to be collected, processed, used, and shared in a broad range of situations that threaten core civil rights and civil liberties. And this is exactly what’s happened, such as when the MSP, in partnership with local police, used drones to surveil Black Lives Matter protests across the state. Under the guise of “crowd control, traffic incident management, and temporary perimeter security,” the MSP was actively surveilling people exercising their First Amendment rights. The MSP should strengthen their policy to prohibit the collection and processing of drone information concerning First Amendment expression.

Finally, the policy is silent on a critical issue: data sharing. As a result, we do not know who has access to drone footage collected by the MSP, under what circumstances, or subject to what type of request. The lack of any information about data sharing is particularly concerning given the involvement of the Commonwealth Fusion Center in the drone program.

How has the MSP used drones?

While the policy sets out how drones ought to be used, emails, communications, and reports show how the MSP actually uses its drones. To that end, we obtained drone flight logs covering the period between January and May 2022. Generally, those records show that drones were mostly used in the following places:

You can access an interactive map here.

Municipalities where the Mass State Police conducted drone flights between January 1 and May 24, 2022

The records show that the MSP used drones for the following purposes during this time period:

- Monitoring Black Lives Matter protests and rallies in Fitchburg, Leominster, Gardner, Worcester, Agawam, and Boston;

- In criminal investigations, for example an attempt to locate evidence related to a New Hampshire State Police investigation (the MSP found no evidence);

- Finding missing persons;

- Mapping accident scenes;

- Mapping airports;

- Transit purposes;

- Investigating the operation of private drones; and

- Training and mapping exercises.

Note that the category “Search & Rescue” includes missions ranging from searching for missing persons to searching for suspects in criminal investigations. Of the 25 flights labeled “Search & Rescue,” at least 7 are related to criminal investigations or searches for suspects, and 18 related to missions looking for missing persons such as elderly people or people with mental health issues. These are very different kinds of missions, and the MSP should group them into different categories in order to facilitate greater transparency and accountability.

Learning more about government use of drones in Massachusetts

The records published here provide a glimpse into drone use at the MSP. But the MSP is not alone—many other police departments across the state use drones. During the summer of 2022, the Public Safety Subcommittee of Worcester City Council was the stage for a public outcry when community members expressed their concerns about the police department’s proposal to acquire drones. The Boston Police Department also has a large drone program.

If you’re interested in learning more about how government agencies in Massachusetts use drones, you can use our model public records request to find out. More information about this process and resources are available through the tool linked below.

If you find anything interesting, please contact us at data4justice@aclum.org.

Boston City Council Hearing on Proposed Ordinance to Ban Face Surveillance

Boston City Council Hearing on Proposed Ordinance to Ban Face Surveillance

On June 9, 2020, the Boston City Council's Committee on Government Operations held a hearing to discuss Councilor Michelle Wu and Councilor Ricardo Arroyo's proposed ordinance to ban face surveillance in Boston's municipal government. Dozens of advocates, academics, and community members testified at the hearing.

Below is a sample of some of the written testimonies submitted in support of banning face surveillance in Boston.

Organizations

National Lawyers Guild - Massachusetts Chapter

Surveillance Technology Oversight Project

Boston Public Library Professional Staff Association

Electronic Frontier Foundation

Academics, advocates, and community members

Woodrow Hartzog and Evan Selinger