Police in Texas, Florida, and thousands of departments nationwide can track Massachusetts drivers in real-time — without a warrant, probable cause, or even reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing. Documents obtained by the ACLU of Massachusetts reveal that police across the state are collecting detailed information about the locations of Massachusetts drivers and sharing that information with a network of over 7,000 agencies and organizations all over the country — including in states that have passed laws banning abortion and gender-affirming healthcare for minors, and laws requiring police to conduct civil immigration enforcement operations.

The records and other publicly available information confirm that over 80 Massachusetts police departments have entered into contracts to deploy Flock Safety’s automatic license plate reader (LPR) technology to surveil drivers when they pass one of Flock’s cameras on the roads. Over the past three years, Massachusetts police have spent over $2 million in taxpayer funds on this technology. Many of these departments have been sharing LPR data collected in their jurisdiction with Flock to be entered into its national database, where it can be accessed by thousands of out-of-state police departments and even federal agencies.

At minimum, this dragnet surveillance means warrantless tracking of everyone on the road. At worst, it means a digital police state wherein law enforcement officials in far-flung jurisdictions outside of Massachusetts can track protesters, political opponents, immigrants, patients, and others not suspected of any crime and use the information to hurt them.

What Is Flock and How Does It Work?

Flock Safety is a major player in the LPR industry, contracting with thousands of law enforcement agencies, running LPR surveillance across nearly 7,000 networks, and deploying nearly 90,000 cameras nationwide as of July 2025. The company’s CEO claims their technology can eradicate all crime in America — though that’s more marketing hype than reality.

License plate readers are cameras that automatically capture and record license plates, locations, and timestamps as vehicles pass by. These AI-enabled systems allow police to instantly track where motorists are now and where they’ve been.

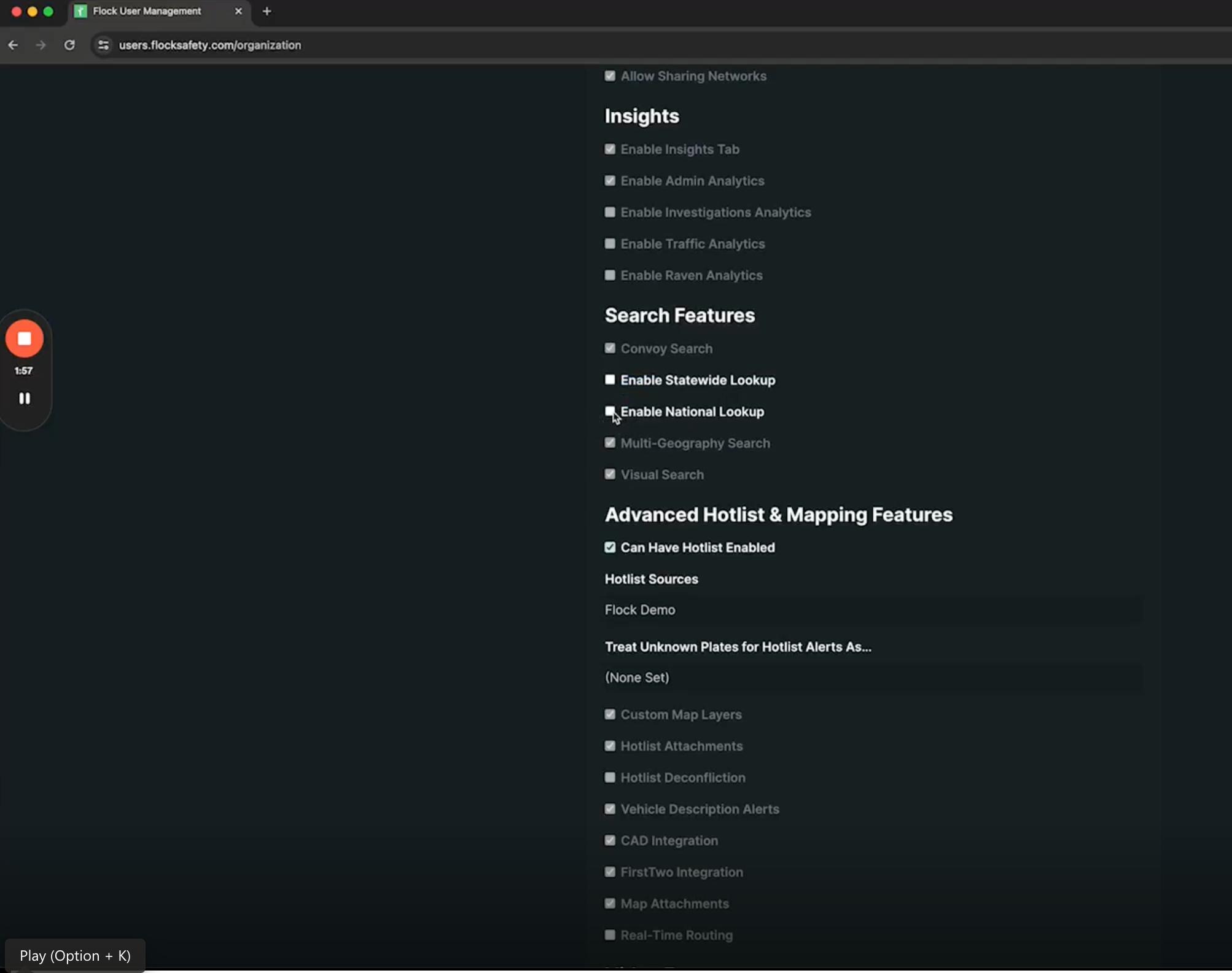

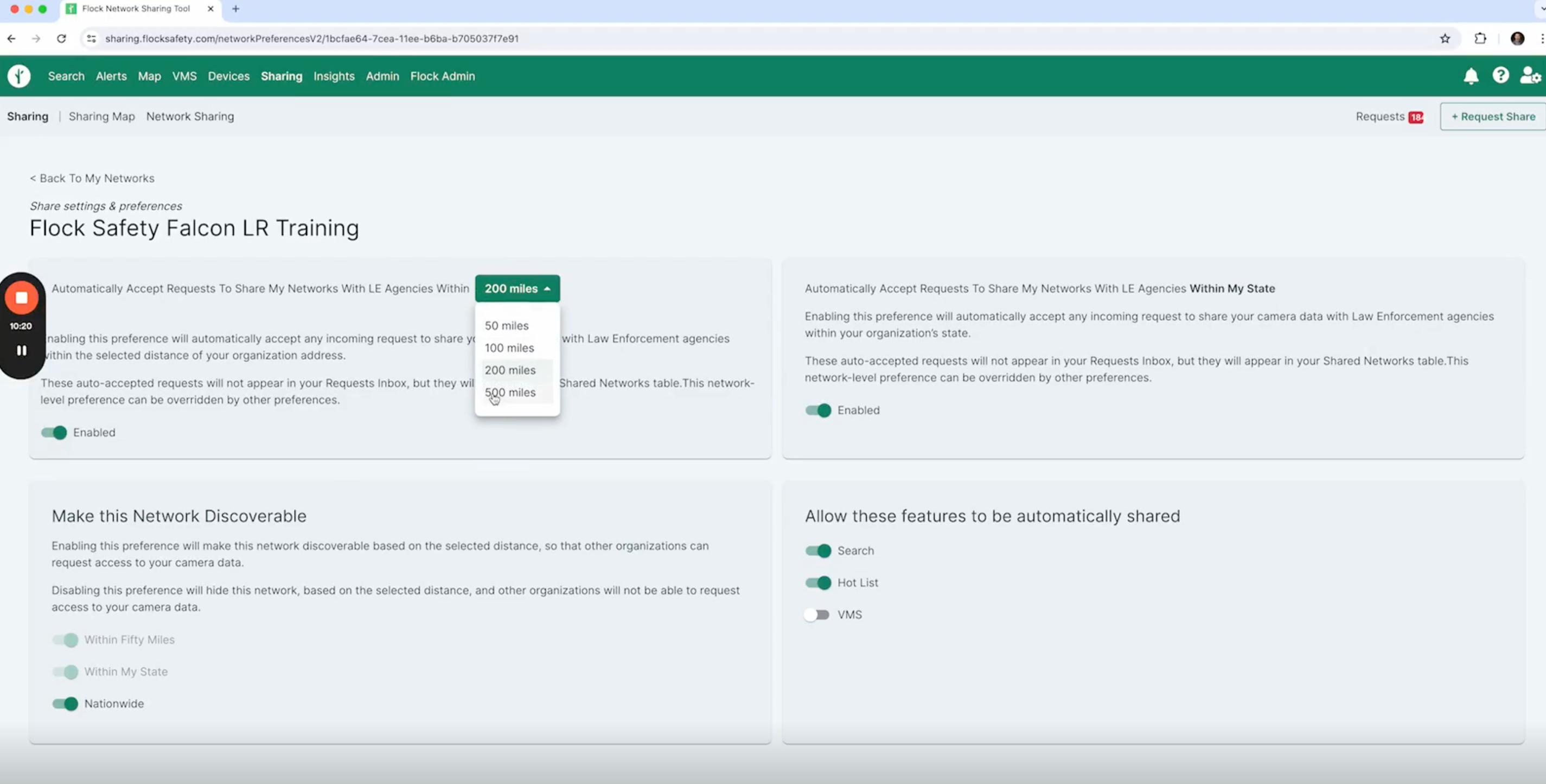

At the crux of the problems with Flock is their nationwide data sharing model. Police departments that contract with Flock can choose to share the LPR data they collect with no other departments, with specific named departments, with all departments in their state, or with the entire Flock network nationwide. But Flock has designed its system to incentivize maximum sharing: if a police department chooses to share their data with the entire nationwide network, that department can also search the entire nationwide network. In effect: “You show me yours, I’ll show you mine.” This Flock training video received in response to public records requests demonstrates how seamless and unrestricted data sharing operates within Flock’s system. To share their data with police nationwide, all an administrator needs to do is click a button:

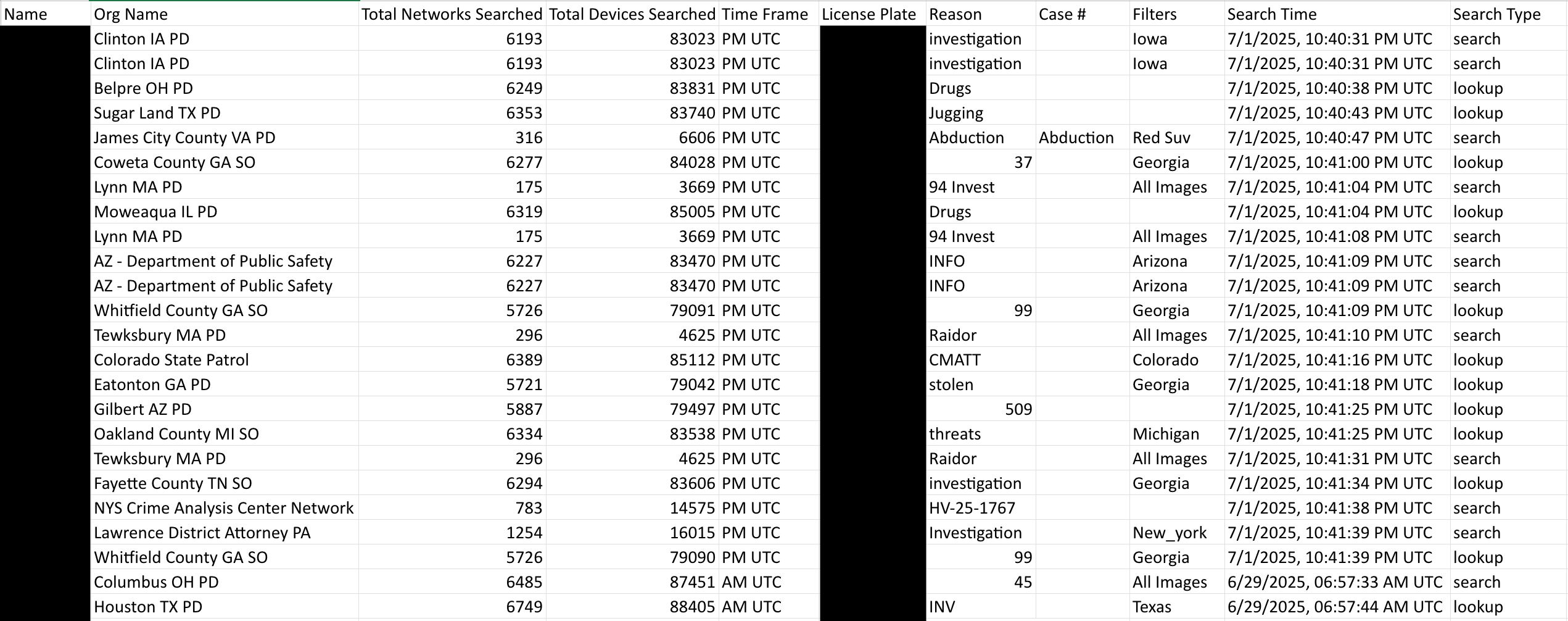

We know many Massachusetts police departments are taking part in this nationwide network because, after submitting public records requests with nearly 80 departments, we received numerous records called “Flock Network Audits[.]” These network audits document searches conducted by police across the country of approximately 7,000 agencies and organizations’ LPR data, including data on Massachusetts drivers collected by dozens of Massachusetts police departments. What this means in practice is that officers with the Florida Highway Patrol and those in Dallas, TX, Jacksonville, FL, Columbus, OH, and thousands of other locations can track where and when Massachusetts residents are driving, even when they are in Massachusetts — all without demonstrating any probable cause or even reasonable suspicion that those people have committed a crime.

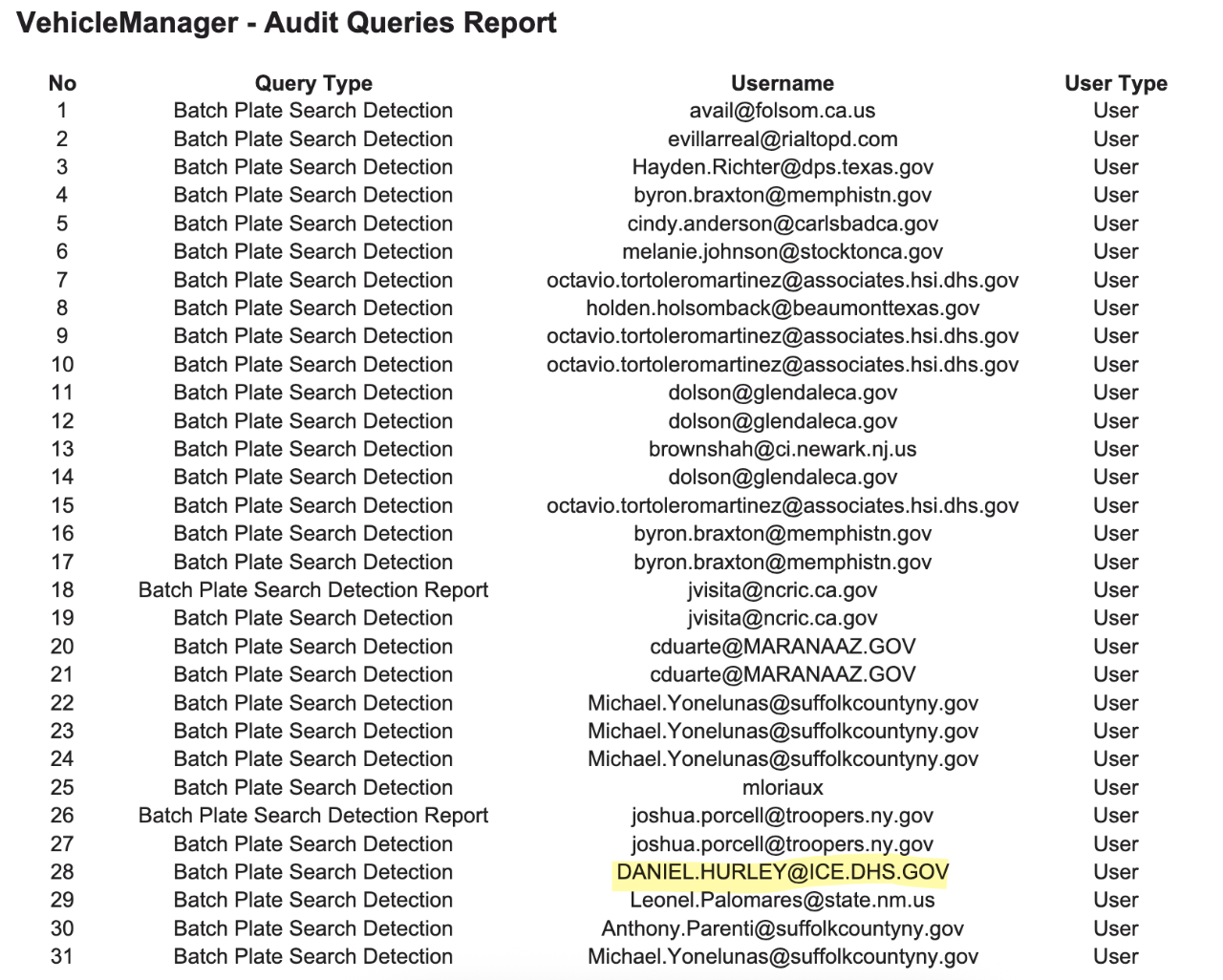

Even some federal law enforcement agencies may have access to Flock’s database, despite Flock’s recent assertion that it ended its pilot program with the Department of Homeland Security’s Customs and Border Protection (CBP). News reports indicate local police have conducted searches on behalf of ICE agents.

And that’s not all. Flock isn’t the only license plate reader company with a large presence in Massachusetts. The Massachusetts State Police (MSP) and some local departments also have contracts with Vigilant Solutions, a company that maintains its own national database and has contracts with agencies nationwide — including those in states that have passed extreme restrictions on abortion and gender affirming healthcare access. Vigilant also has contracts with federal agencies, including ICE. Indeed, records obtained through a public records request to the town of Auburn, Massachusetts show ICE agents have direct access to query the Vigilant database. The ACLU of Massachusetts is currently involved in public records litigation to learn more about the MSP’s license plate reader surveillance network and its statewide LPR tracking database. Stay tuned for more details as that litigation progresses.

Is Warrantless, Dragnet Surveillance of Motorists Legal?

In 2014, in Commonwealth v. Augustine, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that police are required to obtain a search warrant to access cell site location information under the Massachusetts Constitution, the Declaration of Rights. Four years later, the Supreme Court applied similar protections nationwide in Carpenter v. United States. The Court reasoned that technology enabling the government to track everyone, to monitor all our public movements, and to do so both in real time and retroactively, posed a significant threat to our Fourth Amendment rights.

LPRs are analogous to cellphone tracking. These AI-enabled cameras track motorists in real-time and historically, giving the government the means to track people’s locations in a manner similar to the cell site location information at issue in Augustine and Carpenter.

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court recognized this in 2020, holding in Commonwealth v. McCarthy that “[w]ith enough cameras in enough locations, the historic location data from an [LPR] system in Massachusetts would invade a reasonable expectation of privacy and would constitute a search for constitutional purposes.” Yet today, police in Massachusetts are subject to no state or federal statute governing their use of automatic license plate readers. In the absence of a state statute, police are engaged in mass surveillance of all drivers.

Flock’s Data Sharing Model vs. the Massachusetts Shield Law

In August 2024, Massachusetts strengthened its Shield Law, which prohibits Massachusetts law enforcement from providing information or assistance to any other state’s law enforcement agency in relation to investigations into reproductive healthcare or gender-affirming healthcare that is lawful in the Commonwealth. The Shield Law was designed to protect people from other states’ laws that criminalize abortion and restrict access to gender-affirming care, ensuring that people who receive and provide protected healthcare that is lawful in Massachusetts can do so without fear of retribution from out-of-state actors.

But Massachusetts law enforcement’s use of Flock’s nationwide data sharing undermines the effectiveness of the Shield Law. Out-of-state officers from thousands of agencies across the country can and do access information about where and when people are driving in Massachusetts, and there is nothing stopping them from using that information to track the movements of people in Massachusetts who are seeking or providing protected healthcare.

These concerns are not hypothetical. Earlier this year, police in Johnson County, Texas performed a nationwide search in Flock’s database to find a woman who they believed had a self-administered abortion — searching LPR data from many states where abortion is legal and protected, including Massachusetts. We know about this investigation because the Texas officer entered “had an abortion, search for female” in the “Reason” field in Flock’s database. Initially, Flock tried to dismiss criticism stemming from the negative press, suggesting that the woman’s “family feared she was hurt” and that police merely sought to make sure that she was alright. But subsequent reporting from 404 Media based on public records obtained by the Electronic Frontier Foundation show the police who made this search were pursuing the woman as part of a “death investigation” into the abortion. As 404 Media reporters put it: “In documents created prior to the publication of our article, there is zero mention of concern about the woman’s safety. The records show that the police retroactively created a separate document about the Flock search a week after our article was published, in which they justify the search by saying they were concerned for her safety.”

Flock claims it protects people’s privacy and legal rights by requiring all law enforcement officers to enter a “search reason” before accessing database results. According to Flock’s recent response to similar data sharing concerns in other states, if an out-of-state officer enters a reason that would violate a state law that protects access to reproductive and gender-affirming healthcare (for example, Massachusetts’ Shield Law), that state’s LPR data would be excluded from the search results. But the Flock network audits obtained by the ACLU of Massachusetts demonstrate that the company’s measures are woefully inadequate.

The network audits show police frequently enter vague, tautological terms like “investigation” or “susp” instead of information about the substance of the investigation. But even if Flock were to prohibit officers from accessing search data unless they provide a substantive reason, police could evade the system’s guardrails. As Flock’s technology attracts more negative media attention and scrutiny from public officials concerned about its data sharing practices, officers in states that criminalize abortion and gender-affirming healthcare could simply decline to provide specific details about their investigations or use terms like “homicide” or “suspicious death” when investigating an abortion case. The scale of the nationwide searches makes case-by-case oversight impossible. For example, a Flock network audit provided to the ACLU of Massachusetts in response to a July 2025 public records request documents over 450,000 searches of the nationwide database in just a 30-day period in the spring of 2025.

Flock’s purported solution to comply with state laws that restrict the sharing of information related to investigations of protected healthcare services is no solution at all. Today, out-of-state officers continue to have effectively unrestricted access to Flock’s nationwide database, including data about Massachusetts residents and visitors.

Flock’s Contract Problem

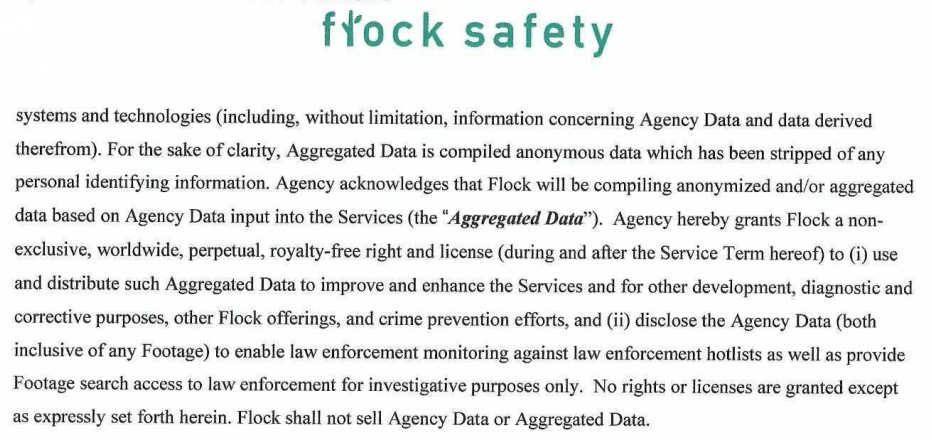

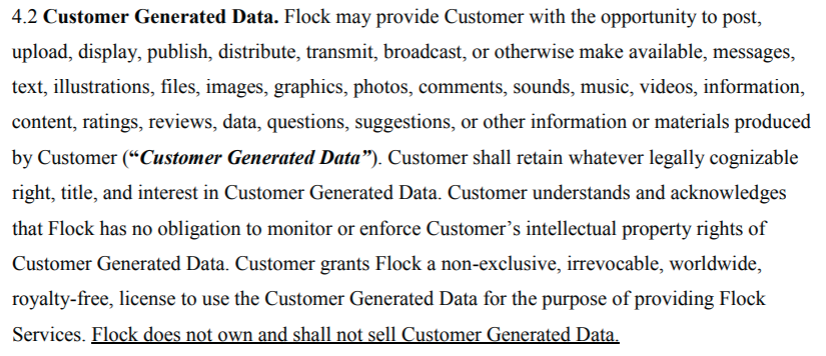

Police departments that use Flock and seek to protect the rights of Massachusetts residents from out-of-state or federal scrutiny must turn off information sharing settings authorizing those entities from searching the data they collect. But even when departments opt to restrict sharing in Flock’s system settings, they may not actually be protecting people’s privacy. According to public records reviewed by the ACLU of Massachusetts, the template user agreement many law enforcement agencies sign gives Flock “a non-exclusive, worldwide, perpetual, royalty-free right and license (during and after the Service Term hereof) to (i) use and distribute [] Aggregated Data to improve and enhance the Services and for other development, diagnostic and corrective purposes, other Flock offerings, and crime prevention efforts, and (ii) disclose the Agency Data (both inclusive of any Footage) to enable law enforcement monitoring against law enforcement hotlists as well as provide Footage search access to law enforcement for investigative purposes only” [italics added for emphasis].

What this means in practice is troubling: even when a police department chooses in Flock’s application to restrict data access to its own officers, the template agreement gives Flock the right to disclose the local police department’s data both to law enforcement nationwide and federal agencies for “investigative purposes.”

Individual police departments can, and sometimes have, addressed this problem by amending Flock’s contract language. For example, when the Boston Police Department (BPD) conducted a pilot of Flock’s technology earlier this year, the department elected in its sharing settings not to share data outside the department — but the BPD also appears to have rewritten Flock’s template contract. Unlike the template contract language that many police departments have agreed to, the Boston Police Department’s agreement does not give Flock the right to disclose its LPR data.

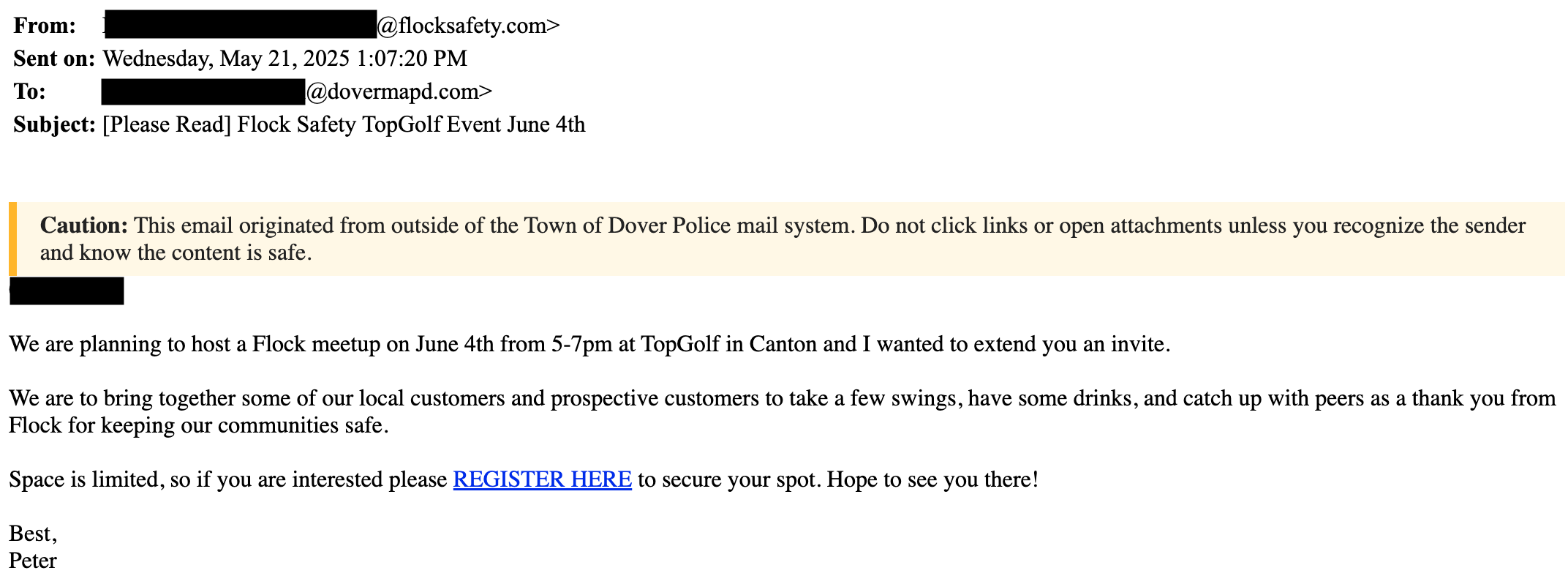

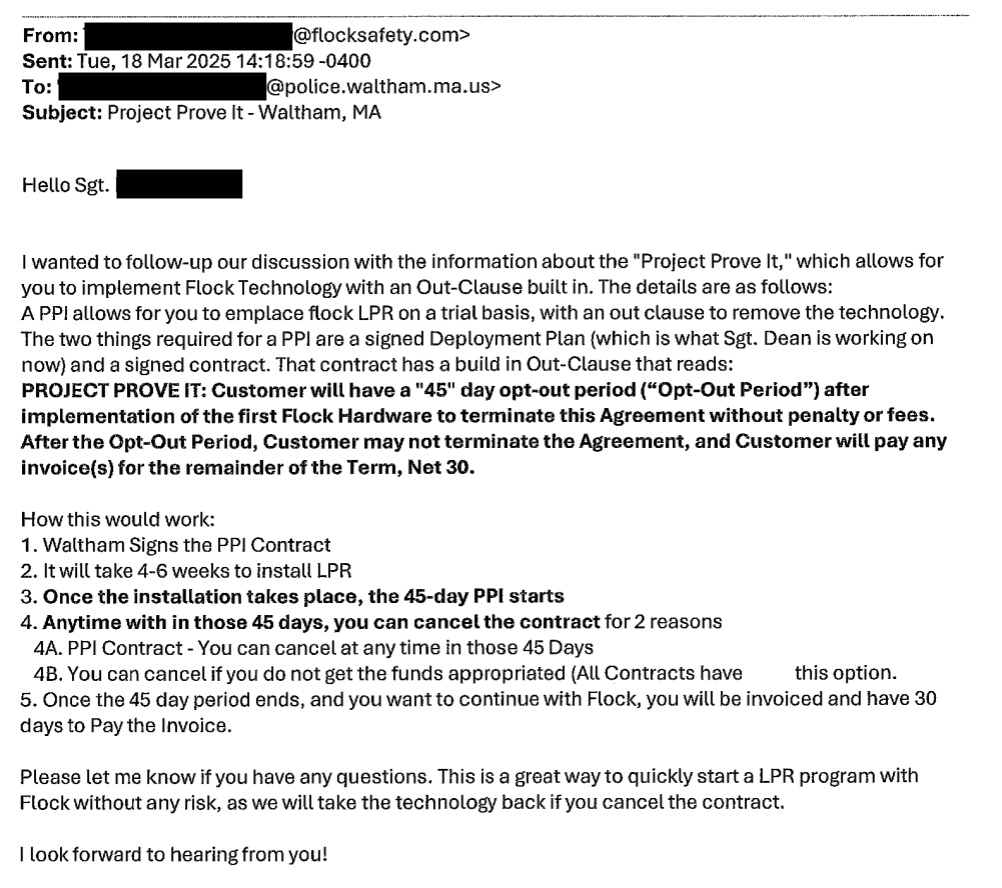

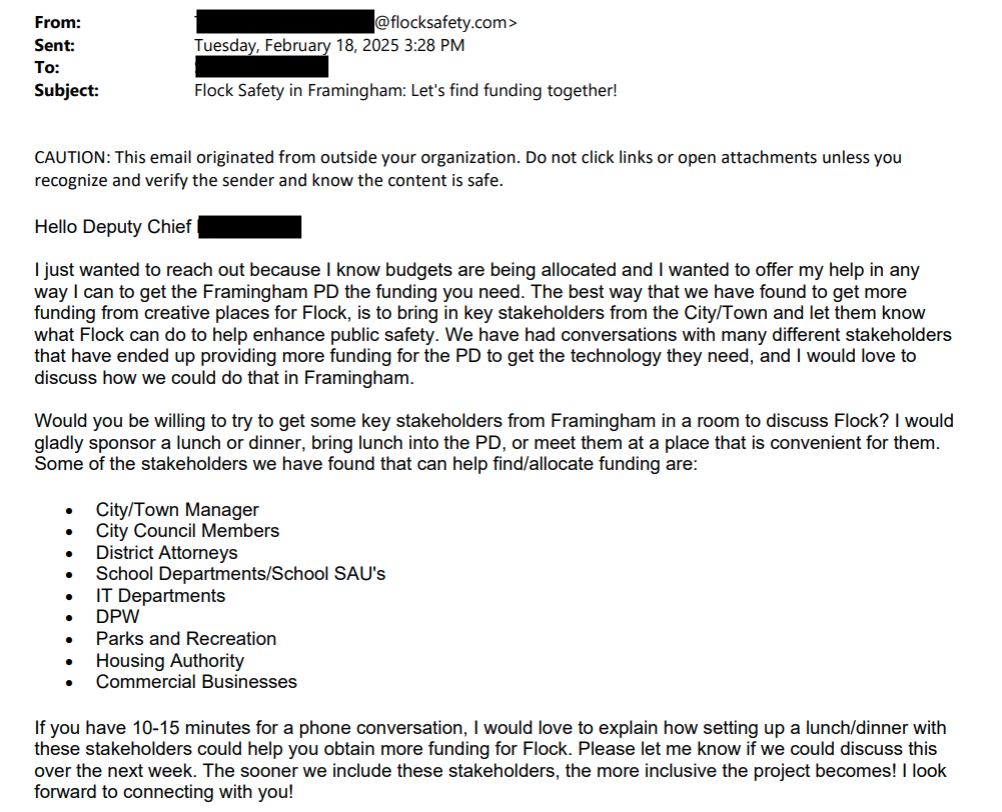

But the vast majority of police departments in Massachusetts lack the legal resources and sophistication of Boston’s department, putting them at a serious disadvantage. Flock, which recently received a large investment from Andreessen Horowitz, has been engaged in an aggressive marketing campaign to win more contracts and secure more taxpayer dollars. This campaign includes potent sales tactics, such as invitations to participate in a free TopGolf event and an opportunity for agencies to participate in Flock’s “Project Prove It[,]” in which Flock installs LPR cameras on the roads and the agency can back out at no cost within 45 days. Flock sales staff also offer to work with local Massachusetts departments and other municipal leaders to identify and apply for grant funding for Flock LPR systems.

Faced with this onslaught from a company with seemingly endless resources at its disposal, small- and medium-sized police departments across the country are falling prey to aggressive marketing and sales pitches. Individual action by sophisticated departments like Boston’s isn’t enough. Residents in communities with less well-resourced departments deserve protection too.

How Lawmakers and Law Enforcement Can Address Issues with LPRs

The scope and severity of this dragnet surveillance make clear that both legislative action and individual police department changes are needed to achieve statewide protections from unrestricted LPR use.

First, state lawmakers must pass comprehensive LPR legislation. H.3755 strikes the right balance, protecting civil rights and civil liberties while allowing police to use LPRs for legitimate investigations. The bill prohibits law enforcement from using LPRs to monitor individuals based on First Amendment-protected activities, including political protests or religious gatherings. It requires that LPR data be deleted within 14 days unless a record is tied to a specific, ongoing criminal investigation supported by articulable facts. Access to LPR data would be limited to law enforcement for investigative purposes and could not be disclosed outside judicial proceedings. The bill also prohibits buying, selling, renting, or sharing LPR and related location data unless required by judicial process, and bars law enforcement from accessing LPR data collected by another entity without a valid search warrant. These provisions prevent the accumulation and sharing of data on millions of people not suspected of any wrongdoing, while allowing law enforcement to use LPRs in legitimate criminal investigations. This legislation would ensure consistent protections apply for all Massachusetts residents.

Second, police departments must take immediate action. Individual departments should stop voluntarily sharing data with out-of-state and federal agencies. They should redraft contracts with Flock to ensure their department retains full control of all data they collect. Finally, police departments must adopt internal policies requiring that every Flock network search be justified by a specific, documented reason for the inquiry, clarifying to all officers and staff that a non-descriptive entry like “investigation” will not suffice.

Take Action

Right now, your movements on Massachusetts roads are being tracked and shared with thousands of agencies nationwide. No warrant, no suspicion, no safeguards.

Join us in calling on the Massachusetts Legislature to pass common sense checks and balances on police use of license plate readers, to ensure that you retain basic civil liberties on the road.

Email your state legislators today to show your support for H.3755, An Act Establishing Driver Privacy Protections.

This post was updated on February 26, 2026, to reflect that more than 80 police departments across Massachusetts have contracts with Flock Safety.