Image credit: Sketch illustration by Inna Lugovyh

The ACLU of Massachusetts has acquired over 1,300 documents detailing the use of ShotSpotter by the Boston Police Department from 2020 to 2022. These public records shed light for the first time on how this controversial technology is deployed in Boston.

ShotSpotter — now SoundThinking — is a for-profit technology company that uses microphones, algorithmic assessments, and human analysts to record audio and attempt to identify potential gunshots. A public records document from 2014 describes a deployment process that considers locations for microphones including government buildings, housing authorities, schools, private buildings and utility poles.

According to city records, Boston has spent over $4 million on ShotSpotter since 2012, deploying the technology mostly in communities of color. Despite the hefty price tag, in nearly 70 percent of ShotSpotter alerts, police found no evidence of gunfire. The records indicate that over 10 percent of ShotSpotter alerts flagged fireworks, not weapons discharges.

The records add more evidence to support what researchers and government investigators have found in other cities: ShotSpotter is unreliable, ineffective, and a danger to civil rights and civil liberties. It’s time to end Boston’s relationship with ShotSpotter. Boston’s ShotSpotter contract expires in June, making now the pivotal moment to stop wasting millions on this ineffective technology.

The records add more evidence to support what researchers and government investigators have found in other cities: ShotSpotter is unreliable, ineffective, and a danger to civil rights and civil liberties. It’s time to end Boston’s relationship with ShotSpotter. Boston’s ShotSpotter contract expires in June, making now the pivotal moment to stop wasting millions on this ineffective technology.

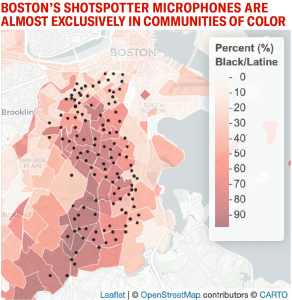

Boston’s relationship with ShotSpotter dates from 2007. A recent leak of ShotSpotter locations confirms ShotSpotter is deployed almost exclusively in communities of color. In Boston, ShotSpotter microphones are installed primarily in Dorchester and Roxbury, in areas where some neighborhoods are over 90 percent Black and/or Latine.

Coupled with the high error rate of the system, BPD records indicate that ShotSpotter perpetuates the over-policing of communities of color, encouraging police to comb through neighborhoods and interrogate residents in response to what often turn out to be false alarms.

For each instance of potential gunfire, ShotSpotter makes an initial algorithmic assessment (gunshot, fireworks, other) and sends the audio file to a team of human analysts, who make their own prediction about whether it is definitely, possibly, or not gunfire. These analysts use heuristics like whether the audio waveform looks like “a sideways Christmas tree” and if there is “100% certainty of gunfire in the reviewer’s mind.”

ShotSpotter relies heavily on these human analysts to correct ShotSpotter predictions; an internal document estimates that human workers overrule around 10 percent of the company’s algorithmic assessments. The remaining alerts comprise the reports we received: cases in which police officers were dispatched to investigate sounds ShotSpotter identified as gunfire. But the records show that in most cases, dispatched police officers did not recover evidence of shots fired.

Analyzing over 1,300 police reports, we found that almost 70 percent of ShotSpotter alerts returned no evidence of shots fired.

In all, 16 percent of alerts corresponded to common urban sounds: fireworks, balloons, vehicles backfiring, garbage trucks and construction. Over 1 in 10 ShotSpotter alerts in Boston were just fireworks, despite a “fireworks suppression mode” that ShotSpotter implements on major holidays.

ShotSpotter markets its technology as a “gunshot detection algorithm,” but these records indicate that it struggles to reliably and accurately perform that central task. Indeed, email metadata we received from the BPD describe several emails that seem to refer to inaccurate ShotSpotter readings. The records confirm what public officials and independent researchers have reported about the technology’s use in communities across the country. For example, in 2018, Fall River Police abandoned ShotSpotter, saying it didn’t “justify the cost.” In recent years, many communities in the United States have either declined to adopt ShotSpotter after unimpressive pilots or elected to stop using the technology altogether.

Coupled with reports from other communities, these new BPD records indicate that ShotSpotter is a waste of money. But it’s worse than just missed opportunities and poor resource allocation. In the nearly 70 percent of cases where ShotSpotter sent an alert but police found no evidence of gunfire, residents of mostly Black and brown communities were confronted by police officers looking for shooters who may not have existed, creating potentially dangerous situations for residents and heightening tension in an otherwise peaceful environment.

Just this February, a Chicago police officer responding to a ShotSpotter alert fired his gun at a teenage boy who was lighting fireworks. Luckily, the boy was not physically harmed. Tragically, 13-year-old Chicago resident Adam Toledo was not so fortunate; he was killed when Chicago police officers responded to a ShotSpotter alert in 2021. The resulting community outrage led Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson to campaign on the promise of ending ShotSpotter. This year, Mayor Johnson followed through on that promise by announcing Chicago would not extend its ShotSpotter contract.

The most dangerous outcome of a false ShotSpotter alert is a police shooting. But over the years, ShotSpotter alerts have also contributed to wrongful arrests and increased police stops, almost exclusively in Black and brown neighborhoods. BPD records — detailing incidents from 2020-2022 — include several cases where people in the vicinity of an alert were stopped, searched, or cited — just because they happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

For instance, in 2021, someone driving in the vicinity of a ShotSpotter alert was pulled over and cited for an “expired registration, excessive window tint, and failure to display a front license plate.” Since ShotSpotter devices in Boston are predominately located in Black and brown neighborhoods, its alerts increase the funneling of police into those neighborhoods, even when there is no evidence of a shooting. This dynamic exacerbates the cycle of over-policing of communities of color and increases mistrust towards police among groups of people who are disproportionately stopped and searched.

This dynamic can lead to grave civil rights harms. In Chicago, a 65-year-old grandfather was charged with murder after he was pulled over in the area of a ShotSpotter alert. The charges were eventually dismissed, but only after he had already spent a year in jail.

In summary, our findings add to the large and growing body of research that all comes to the same conclusion: ShotSpotter is an unreliable technology that poses a substantial threat to civil rights and civil liberties, almost exclusively for the Black and brown people who live in the neighborhoods subject to its ongoing surveillance.

Since 2012, Boston has spent over $4 million on ShotSpotter. But BPD records indicate that, more often than not, police find no evidence of gunfire — wasting officer time looking for witness corroboration and ballistics evidence of gunfire they never find. The true cost of ShotSpotter goes beyond just dollars and cents and wasted officer time. ShotSpotter has real human costs for civil rights and liberties, public safety, and community-police relationships.

For these and other reasons, cities including Canton, OH, Charlotte, NC, Dayton, OH, Durham, NC, Fall River, MA, and San Antonio, TX have decided to end the use of this controversial technology. In San Diego, CA, after a campaign by residents to end the use of ShotSpotter, officials let the contract lapse. And cities like Atlanta, GA and Portland, OR tested the system but decided it wasn’t worth it.

From coast to coast, cities across the country have wised up about ShotSpotter. The company appears to have taken notice of the trend, and in 2023 spent $26.9 million on “sales and marketing”. But the cities that have decided not to partner with the company are right: Community safety shouldn’t rely on unproven surveillance that threatens civil rights. Boston’s ShotSpotter contract is up for renewal in June. To advance racial justice, effective anti-violence investments, and civil rights and civil liberties, it’s time for Boston to drop ShotSpotter.

An earlier version of this post stated that one of the false alerts was due to a piñata. That was incorrect.

Further reading

Emiliano Falcon-Morano contributed to the research for this post. With thanks to Kade Crockford for comments and Tarak Shah from HRDAG for technical advice.